Today’s post includes excerpts from the speeches of the three board member at the GAC conference in DC this week.

At the same time President Biden gave his administration’s agenda update, NCUA board members were given the opportunity to share their leadership perspective with thousands of credit unions in person at CUNA’s GAC.

Whether their remarks are described as a “state of the industry,” “regulatory update,” or even a “future vision,” I thought about topics they might address.

My focus was on issues that would most directly affect credit unions and their members.

Will their remarks offer insight? Will they enhance the credit union brand? What are their priorities? Their tone: concerned or upbeat? Words to be remembered or quickly forgotten?

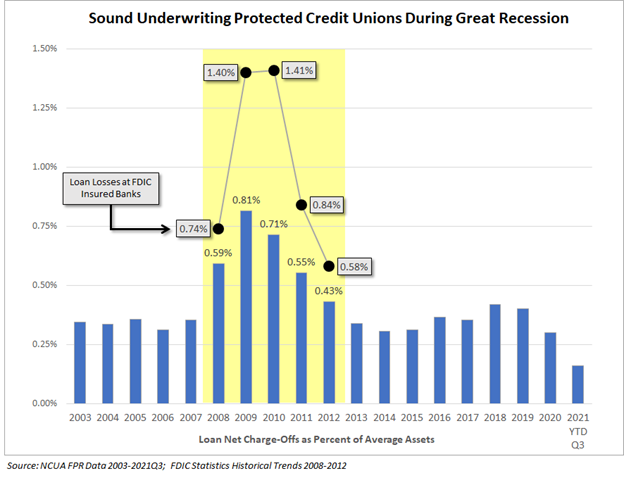

How might the extraordinary role of credit unions with members during the two years of the Covid economic crisis be celebrated? And the movement’s political standing enhanced?

Below is my “listening” list with any relevant comment by a board member. The link to their speeches are on NCUA’s website.

My GAC Topic Checklist

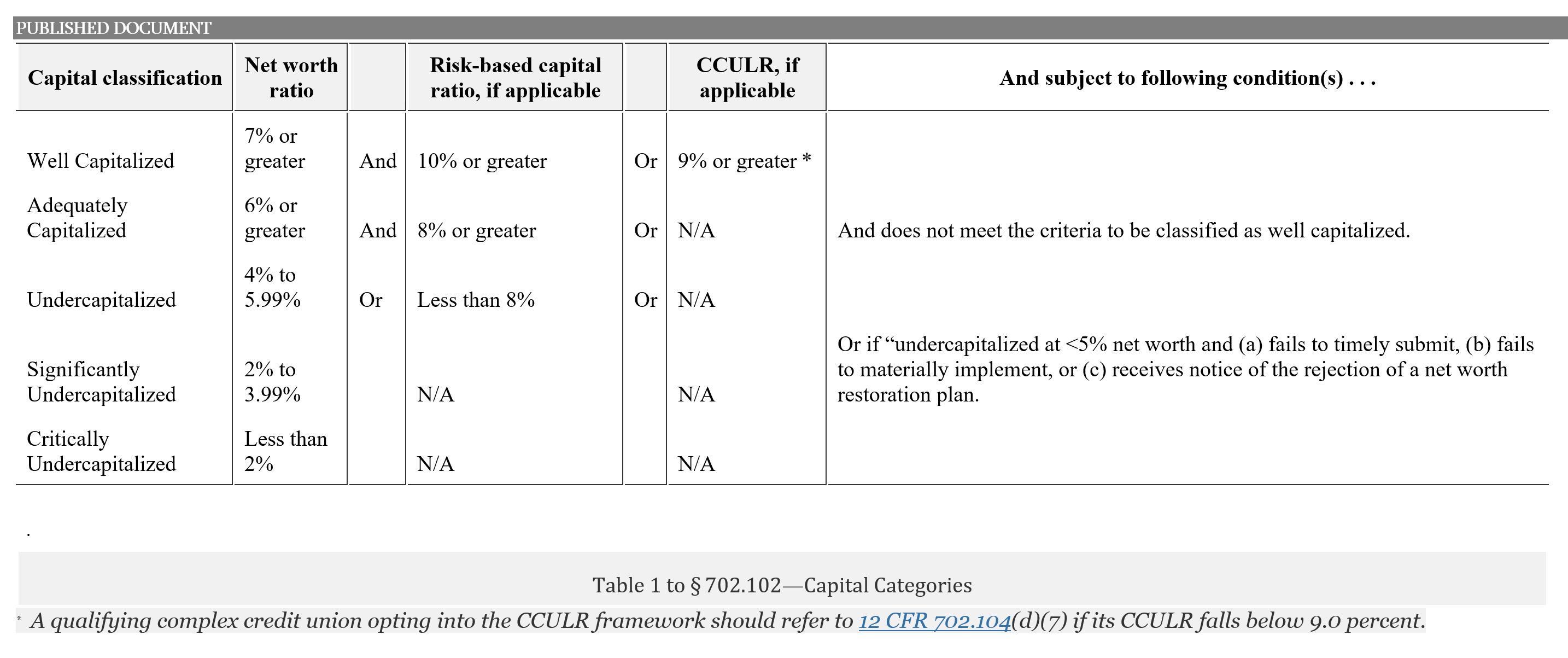

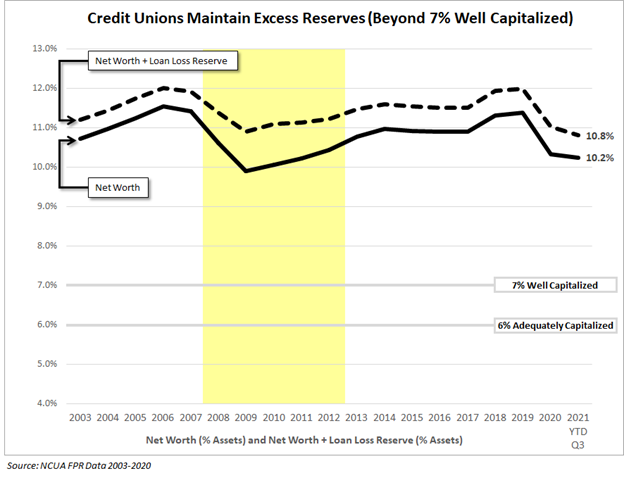

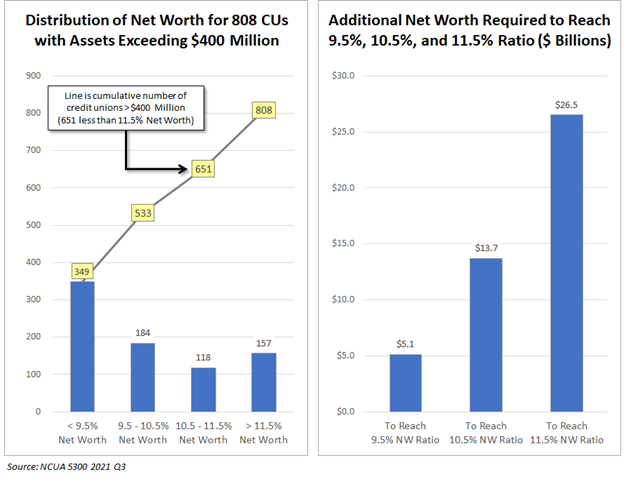

- Why the Board decided to implement the new three-part RBC/CCULR capital requirement within days of being posted in the Federal Register. The rule immediately restricted use of over $26 billion in credit union reserves and required $4-6 billion more in additional capital to avoid the RBC regulatory burden. What was the evidence of a capital adequacy shortfall in the system?

Board Member comments:

- What are board members’ views of mergers of long standing, well-run, and well-capitalized credit unions that result in fewer choices for members and reduce the movement’s financial diversity?

Board Member comments:

- Do board members believe that members’ collective savings compiled over decades should be used to pay off bank owners at premium prices in whole bank purchases? If yes, what should members be told in advance about this expenditure of their reserves?

Board Member comments:

- What do board members believe will be the consequences of low-income designated credit unions’ (LID) increasing reliance on subordinated debt from outside investors to comply with higher new capital requirements and for “acquisitions”?

Board Member comments:

- How will the agency’s two-year experience with remote exams and work from home impact agency costs and effectiveness? Will future staffing needs be lessened?

Board Member comments:

- Is there a special role for the not-for-profit, tax exempt $2.2 trillion cooperative system in American finance? If so what is it? Or should credit unions be part of a level regulatory playing field?

Board Member comments:

- When will the credit union shareholders of the four corporate AME’s $1.2 billion surplus, receive their final payment as the NGN program ended in June 2021?

Board Member Comments:

- Would board members encourage an enhanced democratic member governance role in cooperatives especially at the annual meeting’s election of directors? Would NCUA consider developing a cooperative scorecard, with the industry, to enhance awareness and better implementation of the seven principles?

Board Member comments:

- As individual board members frequently voice a commitment to transparency, when will details of the NCUSIF NOL modeling and the Cotton accounting memo be public so credit unions can understand the logic behind NCUA’s financial decisions? Both are subject of FOIA requests.

Board Member comments:

- Are there any areas where the agency is willing to work collaboratively with credit unions to develop better solutions such as a wider role for the CLF, a more supportive new charter process, or even succession planning resources?

Board Member comments:

- Please share your vision for the future of credit unions given the their record setting performance during the Covid economic shock and recovery?

Board Member comments:

My Summary

Obviously my list and board member priorities differ. None commented on any of these topics directly.

The themes from the talks included fintech partnerships, crypto and block chain’s future, and an important insight from Chairman Harper: Leaders of this industry, like all of you gathered here today, should prudently use your hammers to positively affect the financial prospects of all your members.

Harper did not explain the credit union hammers he was referring to. He made clear the agency would use its hammers for increased consumer compliance. “However, the logic that credit unions do not discriminate because they are owned by their members is a dangerous myth and one that should end.”

If my topics for board members are not yours, it just shows every person has their meat or their poison. Skim the talks. They may respond to your interests or not.

They do however provide an insight on each board member’s view of the industry and his role as a regulator. And maybe you should go out and buy some hammers!