NCUA’s sale of 4,500 credit union members’ loans secured by taxi medallions to a private equity firm is a betrayal of everything the credit union cooperative system represents. Credit unions were founded to protect consumers from being exploited by loan sharks preying on those who have the least or know the least about financial services. NCUA’s sale just put these members and their families at the mercies of Marblegate Asset Management LLC, a firm that exemplifies capitalism’s limitless profit ambition.

These 4,500 borrowers have invested years, some decades, establishing an equity stake with the sweat of their brow, in an earning asset to help them realize the American dream of financial well-being. They joined credit unions and trusted their interests would be treated fairly. Instead the agency regulating the industry sold them out to add additional pieces of silver to a fund bulging with more than $16 billion in liquid assets.

This action irredeemably harms these members whose interests are exactly opposite Marblegate’s. NCUA’s fundamental responsibility is to protect credit union members. This sale places a stain on the entire credit union system. It contradicts Board members’ individually stated policy priorities to treat members fairly, to support financial inclusion, or follow the rule of law.

This deliberate action is an agency wide effort. There was no emergency dictating the disposal of these loans. Rather, NCUA planned for over a year to shed responsibility for the safety and well-being of the very persons credit unions were intended to serve: the member-borrower.

The agency says it worked on this effort for 18 months. When confronted earlier this year with widespread requests by New York City, Congressional and credit union leaders to work collaboratively with the 4,500 members affected, the agency claimed it had to act now or lose its credibility for future asset sales.

It put the buyer’s and its own self interests ahead of the members. Seldom has the well-being of the powerless few been so completely trampled by those with money and authority.

A 2019 New York Times investigation found 950 licensed taxi drivers have declared bankruptcy since 2016. The crushing debt has led to driver suicides. NCUA has now transferred the fate of these credit union borrowers to an investment fund whose reported plan is to acquire the largest share of New York’s 13,500 medallions.

What is Known About the Sale

NCUA provided no facts about this sale. Rather, the media has reported the only public details of this regulatory tragedy.

On February 20, the Wall Street Journal reported the sale to “an investment firm known for buying up distressed assets, will now become the largest single owner of New York City Taxi medallion loans” with this purchase.

Sale price of 31 cents for each $1 of book value

The Journal reported the price of $350 million was for a portfolio of 3,000 New York medallions, 900 Chicago medallions, 500 Philadelphia medallions and 100 from other cities.

This is an average loan value of $77,800 each, all secured by medallions. The estimated par value of these loans is the purchase price of $350 million plus the loss NCUA says it has taken on the portfolio of $760 million. Combined, these two numbers add up to an average book value per loan of approximately $245 thousand.

This total par value of $1.11 billion also suggests that the average price per loan was approximately 31 cents on the dollar, or a discount of more than two thirds from the portfolio’s original book value.

We don’t know what proportion of these loans are receiving regular payments. But many are earning assets backed up with years of payment history. Some will have been rewritten. In every case the medallion security minimizes the possibility of any downside loss. For if the borrower defaults, the security has a cash price that can be monitored in each market.

For example, individuals are offering to buy New York medallions for prices from $125,000 to $135,000 on multiple websites today. The actual sales price for a Chicago medallion since January 1 has ranged from $24,000 to $40,000.

In Boston offers to buy on the web range from $27,000-$40,000.

The following news articles suggest that Marblegate is not interested in loan assets yielding 6% or, if bought at the estimated discount, a yield of 18-19%.

The Buyer: “Profiting from the Misfortunes of Others”

Marblegate Asset Management LLC formed in 2009, is an investment fund focused on buying distressed assets.

A Wall Street Journal article from April 11, 2011, describes Marblegate’s corporate strategy.

For ‘Vultures,’ Slim Pickings — Facing Default, Publisher Lee Enterprises Sells ‘Junk’ to Foil Distressed Investor

The following excerpts from the article describe how these funds try to make high returns, an effort foiled in this case by Lee Enterprises which had been the target of a takeover through purchase of the company’s debt by “vulture” funds. The tactic failed when Lee found alternate financing.

Newspaper chain Lee Enterprises Inc. is on the verge of saving itself from bankruptcy — and many of its debt holders are livid.

Lee, weighed down by about $1 billion of debt, has long been high on the list of potential bankruptcies. But thanks to the roaring market for debt of risky companies, Lee is preparing to sell junk bonds that would enable it to pay off its obligations and give it a new shot at survival.

But what is good news for the company has thwarted the plans of a flock of “vulture” investors — Monarch Alternative Capital, Alden Global Capital, Marblegate Asset Management and a unit of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. — which have been buying Lee’s loans. The group had been betting the company would default, and that they could turn their holdings into an ownership stake, giving them access to the company’s assets, which include St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Arizona Daily Star newspapers.

Instead, they will get repaid, but miss out on the chance to make even bigger profits as owners.

Lee isn’t alone in its sudden pullback from the brink of bankruptcy, thanks to the frothy state of the high-yield bond market. One by one, distressed companies have been able to sell debt as money floods into the debt markets.

That has left few money-making opportunities for distressed-debt investors, who engage in a type of financial schadenfreude: profiting from the misfortunes of others. Vulture investors typically buy debt at low prices, expecting to turn that debt into equity in the company, giving them ownership. Then they can sell off assets or run the company, making more money than they would by simply owning the debt. [emphasis added]

An October 15, 2018 Wall Street Journal article, “Hedge Fund Bets on the Taxi Business” reports Marblegate’s efforts to acquire a dominant share of the New York taxi medallion markets.

Vulture investors are circling the beleaguered New York City taxicab industry.

Hedge funds that specialize in distressed investing have been kicking the tires of the New York taxi market after prices for medallions plummeted amid competition from ride-hailing upstarts. Marblegate Asset Management LLC, a Greenwich, Conn., hedge-fund firm, decided to place a big bet, and over the past year or so has scooped up about 300 medallions for a total price of more than $50 million, according to people familiar with its strategy. (note this would be an average price of $167,000)

Owners of taxi medallions and their drivers in New York and other cities have been hobbled by the flood of app-based ride-hailing services such as those run by Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. There are more than 80,000 vehicles used for ride-hailing services in New York City, more than triple the number in 2015, regulators say. They now dwarf the roughly 13,500 yellow cabs. The competition has led to declines in yellow-cab trips and fare revenue even as the number of passenger trips in for-hire vehicles has soared.

New York City this summer instituted a one-year freeze on licensing new for-hire vehicles while it examines ways to raise driver wages. (note: tis freeze has been extended)

Marblegate, which began buying up medallions last fall at prices between $175,000 and $200,000, isn’t trying to call a bottom, according to people familiar with its strategy. Instead, it plans to operate its own fleet of taxicabs and believes it can run a better business than existing operators — in part by improving working conditions and benefits for its drivers.

At current rates, owners can lease out a medallion to a fleet operator for $15,000 a year, people in the industry said. The operator takes care of cars, drivers and vehicle dispatching, meaning that a buyer of a $175,000 medallion can expect an annual return of 8% to 9%. The price of the medallion is also tax deductible over 15 years.

By operating its own fleet, Marblegate’s returns could be significantly higher. [emphasis added] Aleksey Medvedovskiy, chief executive of NYC Taxi Group, a fleet operator based in Brooklyn, said that some of the better owner-operators today earn about $30,000 annually per medallion, or a 17% return on a $175,000 investment.

Distressed investors buy assets in industries in which disruption has caused prices to decline, wagering they have fallen too far. Investors see New York as the city where traditional taxis — which have the exclusive right to pick up street hails in Manhattan — have the greatest chance of survival. One million passengers hop in a cab, a town car or an Uber each weekday across the city, according to regulators.

“As long as there’s a hail system and a central business district, there will always be business for them,” said Matthew Daus, a lawyer at Windels Marx Lane & Mittendorf LLP who specializes in the medallion industry.

Marblegate’s Strategy: “Furthest Along”

In a July 18, 2019 Crain’s New York Business article, “Mystery Buyer Snaps up taxi medallions as prices fall further“, the state of the taxi medal market is described:

Taxi medallions might be worth less than ever. But in some ways, there has never been more interest in the troubled asset.

Private-equity firms have been circling for the past two years as prices have continued to fall. Marblegate Asset Management of Greenwich, Conn., is the furthest along, having acquired a little more than 300 medallions, starting with purchases at an auction in September 2017.

The firms have different strategies for how to profit from the medallions, according to insiders, but agree that taxis have a future as a key part of New York’s transportation infrastructure. Some see their interest as a bet on the industry’s eventual recovery.

“There are multiple players now—it’s not just Marblegate,” said Matthew Daus, a former Taxi and Limousine Commission member, who is a partner at Windels Marx, a law firm that represents taxi interests. “This is a positive sign.”

The article’s final observation about medallion sales values is also relevant to NCUA’s action: “Bulk sales typically fetch lower prices per placard than individual sales.”

Credit Union Borrowers’ Interests Conflict with Marblegate’s

Even at the discounted prices of the loans which would result in double digit yields, Marblegate’s strategy is to dominate the market for New York taxi medallions to enhance their profitability. Owning medallions is the firm’s operating goal, not administering borrowers’ loans. Refinancing to help individual borrowers pay down loans would just prolong the time before Marblegate might foreclose on a medallion due to driver’s payment defaults.

NCUA has turned these credit union members’ financial fate over to a fund whose sole goal is to maximize return on invested funds.

The New York Post directly addressed this issue. The story was published February 20,2020, the date of NCUA’s board meeting, titled Cabbies Worry as Hedge Fund Snaps Up Taxi Medallions:

Some industry sources said they were skeptical whether Marblegate would be interested in taking a haircut on the loans to help out taxi drivers. “Marblegate is happy owning these assets because they want to own a superfleet and build economies of scale,” according to one industry insider. “The idea is to keep buying the loans, keep foreclosing on them and keep gobbling up medallions until you control the market.”

How could any individual borrower ever hope to renegotiate loan terms with Marblegate? They want the medallion, not a loan, that if paid off would take away their prospect of owning the medallion via foreclosure.

A Credit Union Times story the same day quoted the Bhairav Desai, executive director of New York Taxi Workers Alliance that they hoped to restructure the loans at uniform value of $150,000 each. Instead NCUA sold the loans for $77,000 each. The borrowers received no benefit from this sale and are still burdened with debts incurred in very different market circumstances.

Marblegate acquires the debt at a very steep discount. The members are shut out from any upside potential from the sale.

NCUA’s Moral Blindness and Administrative Stonewalling

NCUA has turned its back on common sense and its fiduciary obligations to the cooperative system.

NCUA has charged the cost of the resolution of liquidations to the credit union system but then given all the potential upside profits to the private sector to reap. Co-ops pay for all losses. For profit firms reap the gains.

There are no facts provided in the NCUA press release, the FAQs or board oral statements defending the sale. The rhetorical explanations are entirely unsubstantiated. There have been no criteria for the solicitation process, no details about the financial advisor’s purpose or recommendation, no comparison of different options, no data on administrative costs, and no information on portfolio performance provided to explain this decision.

Somehow the general press (Wall Street Journal, MSN and New York Post) were able to find these details. This fact vacuum suggests NCUA either does not have data to support the sale process or is afraid the data would not justify their action. Vague assertions and generalizations replace evidence.

NCUA’s Illogical Explanations

The hollowness of NCUA’s arguments is staggering. McWatters is quoted: “We are fiduciaries for the insurance fund. We needed to take this offer.” Without a single fact to back up why a $16 billion fund needs more cash liquidity.

The most absurd statement in NCUA’s press release is “Private entities have specialized skills and greater resources and flexibility to work with borrowers in ways the NCUA cannot.” I will not argue with NCUA’s confessed lack of competence. But are they also ignorant of the billion-dollar credit unions and CUSO’s that manage taxi medallion loans as an everyday part of their business with specialists that know how to work with members?

NCUA has dissed the expertise, capabilities and experience of the credit unions they oversee in turning the future of these members to a “vulture” fund over which they have no control. They have sold out not just 4,500 members, but the entire cooperative system’s reputation and replaced it with a private, profit maximizing fund’s financial ambitions.

Compounding this demeaning assessment of credit union’s expertise, this bulk disposition of distressed assets will only harm credit unions with loans secured by the same collateral. The public fire sale which writes off two thirds of the book value of loans, can only harm the valuation of loans now held by credit unions in the same asset class.

As for NCUA’s claim that this was “the least long-term cost” every known fact about this case suggests just the opposite conclusion. The agency took the highest and greatest loss possible forgoing all future revenue from these loans. The upside opportunity is not tied to medallion values, but rather to the borrowers’ abilities to make affordable payments on their debts as they strive to achieve full medallion ownership.

At a fire sale average price of $77,000 (or the higher $150,000 amount proposed by the Workers’ Alliance), it is inconceivable that these experienced borrowers and taxi drivers could not meet rewritten payment terms and create a win-win for them and the NCUSIF.

Invoking Congress and “Mission”

The statement that “failure to achieve an orderly liquidation at the lowest long-term cost would violate the NCUA’s Congressionally mandated mission of protecting the insurance fund” is nonsensical. It is supported with no facts and in essence suggests that Marblegate doesn’t know what it is doing due to these so-called long-term costs. I suspect that this investment fund knows exactly what it is doing and has calculated that the long-term revenue returns that will enable it to dominate the taxi medallion business in New York and other cities. The statement merely confirms the agency’s analytical myopia.

When has NCUA ever justified an action by invoking a “Congressional mandate? If that is the reasoning whatever happened to the “Congressionally mandated mission” to help cooperative borrowers?

The sudden action (Feb. 19) by NCUA after numerous inquiries and efforts by the New York City Council and other interested parties suggests NCUA wanted to lock in the loss on these liquidations. Before the liquidation of the two credit unions, the NCUA-appointed conservators had estimated the combined negative net worth of LOMPTO and Melrose at $150 million at June 2018. In the September 2018 liquidation, NCUA recorded a $760 million expense against the allowance account.

This was an estimate already recorded in the December 2017 NCUSIF audit, over two years before this February 2020 sale. Any resolution that would contradict this prescient estimate would be embarrassing for all involved. So best to lock in the loss projected with amazing foresight so there is no need to explain how a $150 million deficit balloons to $750 million three months later.

And the $350 million just happens to be the net recovery value NCUA estimated when they expensed the allowance account over two years earlier. It is indeed remarkable how accurate this loss forecast proved to be compared to the absence of any contemporary data to support the sale today.

Who Will Join the Members’ Voice?

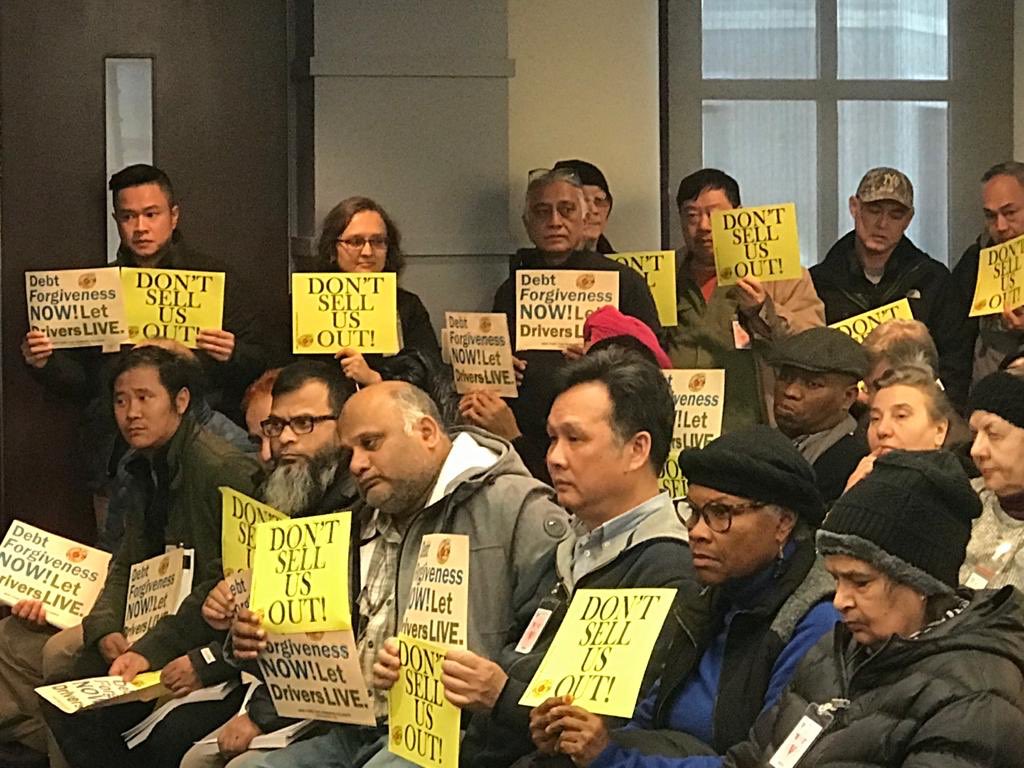

Following the NCUA meeting on Feb. 20 in which the taxi drivers’ signs were taken away and many routed away from the board room, one taxi representative summarized the board’s actions: “They sold us out today.”

The day following the Board meeting the New York state attorney general ordered the city to pay $810 million to debt-hit taxi drivers. The demand stated that the city allowed brokers and top players to collude on prices. The demand claimed the Taxi Limousine Commission marketed the new medallions as a path to the American dream.

Some commentators question whether this demand has any merit, but it shows two things. The possibility of assistance for taxi borrowers from unexpected sources. More importantly for NCUA, it demonstrates a government entity willing to try to help the borrowers, not walk away as NCUA has done.

NCUA’s explanations of the sale are neither credible nor convincing. The entire process was done in secret. Those most affected were never consulted.

This event raises the prospect that NCUA has become the weakest link in the cooperative network. For if members cannot rely on NCUA to protect their interests in this relatively small, highly visible event, what confidence should the 100 million plus members have that their interests will be safeguarded in the future?

This event is not an individual failure in which an examiner or survivor made a mistake or showed poor judgment. Rather this is an institutional failing from top to bottom over an extended period.

And that is why this betrayal has significance for every person concerned for the future of the cooperative system. To be silent is to give consent. Leadership tales courage. Shouldn’t Congress ask how this sale of members’ future fulfills NCUA’s cooperative mission?

Print This Post

Print This Post