For four decades (1979-2017) the State Employees Credit Union was led )by Jim Blaine. He believed in the power of cooperative design, principles and purpose to provide members a better financial option.

His approach was so successful that SECU soared in his tenure to become the second largest credit union in America. At March 30, 2025 the credit union reported assets of $55.3 billion, members of 2.8 million with 275 branches (one in every county) employing 8,100 FTE positions.

Growing a Unicorn

Blaine’s studied belief in the power of cooperatives infused dozens of operational and strategic decisions. He eschewed mergers preferring to partner with other credit unions such as Latino Community and Local Government FCU to support a strong state eco-system of credit unions.

His focus was strictly within North Carolina, not seeking to invest outside the members’ home state. Within the FOM the focus was on those who were unlikely through economic circumstance or financial understanding to get a fair deal from traditional for-profit consumer financial options.

Creative Product Designs

His implementation of these beliefs resulted in some unusual product decisions. The lending focus was on home loans as the best way to build long term member wealth. Products such as credit cards and checking were simple, low cost and without flair. He created the only 529 on balance sheet college savings option by a credit union in America.

He provided off balance sheet investment options in a partnership with the Vanguard Mutual Fund family of low-cost index funds. The credit union founded its own life insurance company for inexpensive term life insurance. Through a $1 a month checking account debit he funded the largest credit union directed 501 C 3 foundation. Annually it donates tens of millions to organizations serving the needs of citizens and communities throughout the state. These grants were the credit union’s primary marketing effort-an example of earned versus bought media.

As the credit union system adopted risk-based lending, where a member’s loan rate was determined by their credit score, Jim fiercely resisted this almost universal pricing practice. He believed the model was discriminatory and perpetuated some of the consumer lending practices coops were meant to counter such as, those who have the least, pay the most for their loans.

Likewise, he did not believe in indirect auto lending in which the dealer set the member’s loan price based on the credit union’s buydown rate of the loan paper.

Internally the credit union grew large by staying small. The 275 branches were given authority to make and collect loans for their communities. They were aided with local advisory councils of members for decisions on scholarships, grants and even denied loan appeals. Vacancies were first filled from promotions within. No commissions or bonuses were paid to staff-just follow the principle of doing the right thing for the member.

Most importantly the credit union’s capital investments were always on behalf of members or the local community. From a surcharge free ATM network for all users, not just SECU members, to housing a museum in its main office building, to the Foundation’s investments in low cost teacher housing options, the money was to benefit owners and their communities, not for the institutional prestige of SECU.

Many organizations including large credit unions use their home market as a resource to open up into areas outside their core. Members’ resources do not go back into the local economy that funded their initial success, but into new markets.

Jim’s “old-fashioned” approach was not one emulated by others. He battled NCUA time and again over capital adequacy. “Anything over 7% is stealing from the members” was one of his truisms. At March 30, 2025 the net worth ratio was 10%. In short, while reporting superior market impact and financial performance, his approach was seen by most peers as archaic, impractical and not with the times.

The Two CEO Succession Rule

One observer has asserted every successful credit union coop is only two CEO successions from losing their strategic heritage and advantage. When he retired in 2017 Jim’s successor was his CFO Mike Lord. A good description of Jim’s ten operational priorities and the succession evet is in this creditunion.com report. The torch was passed to a believer who had worked at SECU for 41 years, or as one headline read, “Only the Lord could succeed Blaine.”

But when Mike Lord retired the board went outside the credit union apparently seeking a change agent with a different vision for the future. Jim Hayes took charge in September 2021 leaving the $2.2 billion Andrews FCU as CEO. He had previous positions at WesCorp and NCUA.

Members Challenge the New Direction

The October 2022 SEU Annual meeting was going according to the agenda until the other business item. At that point former CEO Blaine, now just a member, rose with a prepared statement.

He asked how recent credit union actions were in the best interests of SECU members. The event and issues are described in this blog, SECU Members’ Spirits Awaken. The members approved Blaine’s two motions. one asking for a response to the six areas of concern. The second read: The Board update, publish, and make available to all member-owners its’ Strategic Plan for SECU no later than 90 days prior to the 2023 Annual Meeting.

Six months after credit union fireside chats and other communications responding to the motions, Jim launched a public blog SECU-Just Asking! He re-presented the issues that energized members and employees had asked him raise at the Annual Meeting.The blog became the platform for members nominating their own candidates for board openings at the 2023 Annual Meeting.

Members Electing Directors

In 2023 the concerned members nominated three candidates who supported their views for the open board seats. Around 14,000 members voted in the contested election in which all three board nominated incumbents were ousted. The members had succeeded in challenging the changes via the election process.

In 2024 the election was again contested and almost 100,000 members voted. This time the incumbents were reelected, but the top alternative candidates received almost 30,000 votes. SECU spent substantially to promote incumbent s in this second contested election.

The 2024 meeting was broadcast live on YouTube. My closing blog observation was: One cannot help but come away with the feeling that this year’s event was a reaction to the two prior meetings where the board must have felt things moved out of their control. This time the outcome which had some excellent content, especially the member questions, was an exercise in the power of incumbency.

The Public Debate Continues

Since the launch in March 2023, the Just Asking blog has cumulative views of 2.53 million and 14k posted comments, according to Blaine. He says interest peaks as the board election cycle gets under way in July/August. Currently views average around 2,500 per day.

By any measure it is a blog followed by a significant number of SECU members and one presumes employees. The blog is a unique member-owner effort in its longevity and substance trying to influence the credit union’s direction .

Jim Hayes, the new CEO implementing the changes challenged in the October 2022 Annual Meeting, left in June of 2023. The board promoted the long- time COO Leigh Brady who has continued most of the internal and member-facing changes.

The controversy has somewhat slowed the credit union’s momentum. When Mike Lord left in August 2021, the credit union was $50 billion in assets versus today’s $55 billion (a 2.5% cagr)

A New Unicorn for Coop Believers

Today as SECU evolves into a traditional credit union provider, it remains a Unicorn for another reason. It is the only large credit union to have contested board elections for the past two years. This member-owner involvement is unique and yet what the coop design was intended to ensure. The members’ role using the democratic principle of one person, one vote, is the critical governance function.

Member choice in contested elections is essential to active owner accountability versus the habit of internal succession controlled by sitting board members.

Democratic organizations (or countries) rarely fail because of external market competition. Rather most failures come from within. They are leadership and commitment shortcomings.

The two CEO successions from failure observation is a critical issue for credit unions. Financial failure is very rare, but failure to grasp and enhance the unique business design and principles that are the foundation of every credit union can be quickly lost. New visions and corporate aspirations can take credit unions away from their special strenths.

Credit unions were founded with no capital, just human passion, When that initial belief is not sustained, the accumulated net worth can just become the CEO and board’s treasure chest, not a member-enhancing resource.

Controlling Member Involvement

SECU’s policy and financial performance continue debated in daily posts, The credit union’s primary response has been to limit or eliminate the members’ role in the annual meeting activity.

In the last two years SECU’s board has changed its bylaws to better control the annual meeting and election processes. The agenda has been closed to open member discussion. The timing and procedure for member nominated candidates in elections have been shortened making it more difficult for non-incumbents to get on the ballot.

In short, the board has tried to shut down the effort that raised the original concerns in 2022. The unique coop member governance check and balance on credit union priorities is being stifled to the point of elimination. And following recent blogs, the NC state regulator is trying to avoid any oversight of the board ‘s efforts to eliminate all member governance rights.

Why this Members’ Unicorn Effort Matters

This issues profiled by Blaine are not an isolated concern. Other credit union members are facing similar challenges in being heard. Rarely does a merger go by without some members asking why? Bank purchases using members’ accumulated capital rewards bank owners, not the credit union’s owners.

The future of the country’s second largest credit union has implications for the cooperative system as member-centric financial alternatives. Members are seeing investments disconnected from their well being or traditional purpose.

When owner involvement is silenced at required annual meetings, a credit union’s future is in the control of self-selected, perpetual unelected volunteers. That is a dangerous separation of responsibility from accountability when owners are left out.

There is now over $250 billion in collective reserves under credit union boards’ control. Keeping the 100 million coop member-owners from influencing how these funds are used will bring temptations from all corners of the capital markets, brokers and hedge fund investors.

Boards will feel free to do whatever they choose, initiatives unhindered by either principle or purpose. Dramatic visions of power and influence financed with billions of members’ collective wealth willl be in play.

With members seen as only customers, just a means to greater ends, the cooperative alternative will have lost its way.

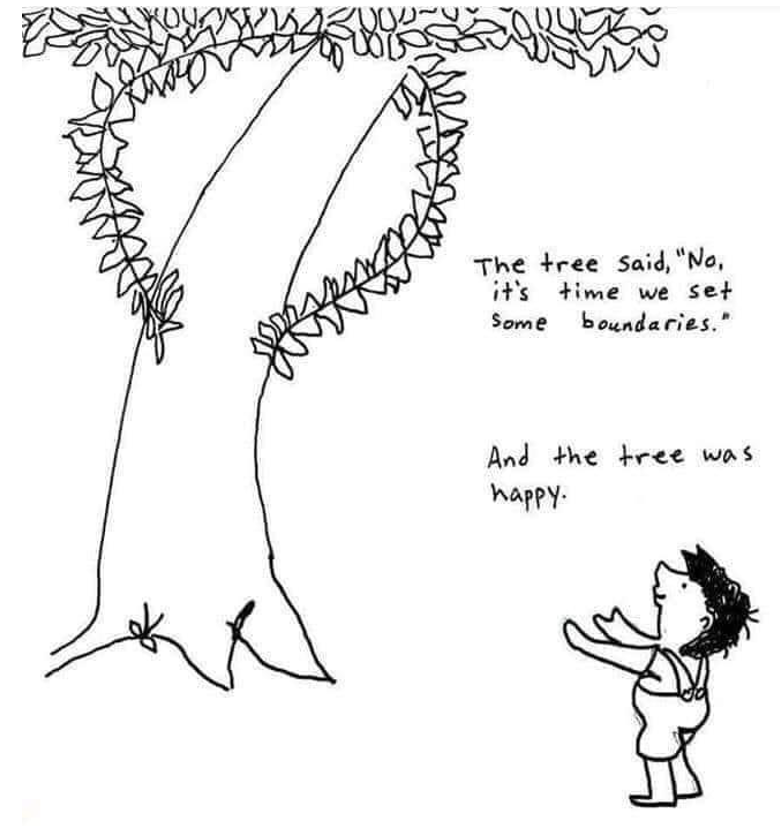

Speaking Truth to Power

From Socrates and throughout Old Testament stories, the prophet’s voice has been a source of wisdom and discomfort for those in authority.

The idiom “a prophet is without honor” comes from the New Testament. It refers to someone whose message is not appreciated by their own community.

It takes unusual courage to make a public stand against those in authority. When done by someone with expertise and experience, they will be accused of failing to give others their turn at the wheel.

Blaine is blunt even caustic at times in his writing. He does not believe in nuance. When others are not direct, he will call out lies.

He believes coops were designed and have the responsibility to correct a fundamental flaw in consumer financial services. In his words, “those that have the least or know the least, pay the most for financial services in America.” The problem has only gotten worse as income inequality continues to grow.

Credit, that is consumer borrowing, is the most important way for almost all to succeed in a free market economy. There are no scholarships for life’s essential purchases.

Yet when CEO’s and Boards’ tenures grow to oversee hundreds of millions or billions in assets, it is tempting to gravitate towards those well-off in life. Making Tesla or Lexis auto loans is a better opportunity than members needing to buy a car at an Enterprise used car sale.

Events will influence how Blaine’s initial six concerns will resolve. Local Government FCU, now Civic, has ended their partnership with SECU at great cost to both sides. Risk-based pricing may or may not increase SECU’s consumer loan share. The question is whether real estate lending continues to be a priority or whether it will convert to just another “conforming” service.

Blaine’s most recent effort to request the North Carolina regulator to preserve the rights of members in overseeing their coop may seem ironical given his history of battling NCUA when CEO.

But that issue is the bottom line now, not differing judgments about products or services. SECU is at a turning point, already taken by most. Will the rights of member-owners to be heard with their elected leadership be upheld? Without that check and balance, there will be billions of dollars of members’ collective resources without any accountability.

I will give Blaine the last word from this brief statement on the role of regulation in 2010.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E1tnDcE6Xjo)