When I was a member of Ed Callahan’s team, he would offer two thoughts when evaluating uncertain situations: The first was “Never say never,” when talking about future possibilities. The second was “What are the options” when working through a challenge.

Each day brings more Washington rumors, supposed plans, new faces and real events that have led to increased uncertainty for NCUA and credit unions under the Trump overhaul of the federal government.

Those who see changes as a threat to the independent co-op system are urging credit unions to prepare for battle, increase lobbying efforts and deploy new member engagement tools. Others will go with the flow assuming they will be OK if they stay invisible as part of a herd of 4,500 institutions.

If a never-say-never event unfolds, how does one prepare for it? Are there options that should be ready to go beyond the standard lobbying or “fight back” efforts?

A Short Credit Union History

The most important means of acting as a check to an overreach or an unresponsive federal regulatory environment is the dual chartering system.

Credit unions were birthed and spread first in the state legislatures. From 1909 until the Federal Credit Union Act passed in 1934, over 25 states authorized local and varied credit union charters. These multiple state examples were the “proof of concept” that gave Congress the example to extend this unique member-owned design to all states via a federal chartering option.

But state innovation did not end with this beginning. Senator Proxmire in a 1984 hearing stated he received his first real estate loan in the 1940’s from a credit union. FCU’s did not have real estate lending power until 1978. State systems pioneered the introduction of NOW (checking accounts) in Rhode Island and share drafts in other states before this transaction authority was given all financial institutions in the Monetary Control Act of 1980.

State charters led the way in deregulating rates and terms on savings years ahead of the DIDC and NCUA action in 1982. State options have had much more flexible fields of membership, CUSO investments and other varied business options.

State credit unions lead federals in transparency with their required annual IRS 990 reports. These filings disclose director and senior executive compensation as well as listing all 501 C3 contributions and political donations, if any.

Dual chartering has been a source of diversity, change and responsiveness to local conditions. The NCUSIF’s regulations, including the risk based capital requirement, impose a one size fits all accounting and capital model on a very diverse industry.

The Critical State Advantage

However, there is one option that keeps the independent role of the state system intact. That is the opportunity, currently in ten states, for their credit unions to choose private versus NCUSIF deposit insurance.

At yearend ASI, the Ohio based deposit insurance company, covered the shares of approximately 100 credit unions with $23.4 billion in assets serving 1.4 million members. Six of these insured firms have over $1 billion in assets; seven have less than $1.0 million. The average asset size is $240 million.

Expanding CU Choice Across the System

Recently ASI presented a webinar as part of a campaign called CUChoice. The focus was on Michigan credit unions to encourage their support for a legislative change to give state charters a choice in their insurance coverage.

The full recording of the webinar is here.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hP-QN8HazKA)

The slides present the advantages of ASI vs NCUSIF. Points covered include credit union ownership, a member-elected board of directors, and the specific role of an insurer that is not a regulator. ASI’s focus is on being a business partner with its credit unions in which interests are aligned.

Slides 13-29 are a presentation by CUNA’s long time chief economist Bill Hampel, now retired. In his talk he discusses the advantage of a Michigan state charter and compares the performance history of NCUSIF and ASI from 2007 though 2013. He directly answers the vital question referred to as the tall tree issue by showing how the two insurers compare in size to their single largest credit union. (slide 22)

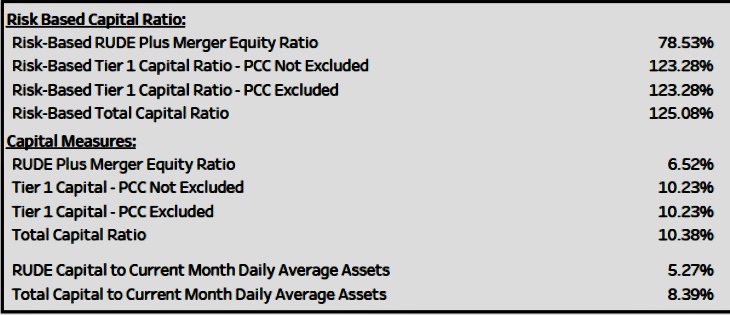

Slide 29 is a detailed comparison of ASI’s equity to insured coverage ratio of 1.75%. to the NCUSIF’s 1.31%

More Than a State Charter Option

The choice of deposit insurance has benefits far beyond state charters. The option enhances the vitality of the entire dual chartering cooperative model. In those states with an option, Hampel presents data suggesting those states have stronger performance.

Having an option prevents NCUA from being a total monopoly and provides real time performance comparisons. For example, ASI financial audits and reports follow private GAAP accounting, whereas the NCUSIF in 2010 adopted federal GAAP. This federal standard mischaracterizes the NCUSIF’s operations and distorts the NCUSIF’s year end financial position. Also ASI must comply with reserving requirements under both GAAP and state insurance regulations.

ASI’s most critical difference is You Do Own It. The credit union elects the board and there is an appointed advisory group. The users have a direct say and responsibility for the management of their collaborative fund.

ASI has a performance track record as long as the NCUSIF. That history had a direct impact when the NCUSIF’s financial model was redesigned by Congressional legislation in 1984. The 1% deposit model, which provides the earnings and equity foundation for the fund’s financial stability, was a direct borrowing from ASI’s structure and experience.

By offering choice, ASI provides all credit unions a check and balance on the unilateral power of a monopoly insurer/regulator. The choice follows the unique constitutional system of state and federal powers. It rests on the cooperative values of self-help and collaboration.

No one knows what the future of federal regulatory and insurance systems will be under Trump’s administration. Credit unions should further enhance their options now building on their unique dual chartering roots.

In all other areas of Americans’ insurance coverage-life, auto, health and many more, the licensing and regulation responsibility rests solely at the state level. There is no federal option-except for deposit insurance. ASI is an example of this responsibility and choice that makes the credit union system more resilient and viable than any other model yet created.

Uncertain about outcomes at the federal level? Act now because no one knows today what you might need tomorrow.