In this second blog I look at examples of goodwill. What are some of the financial and regulatory implications of this ever increasing intangible asset?

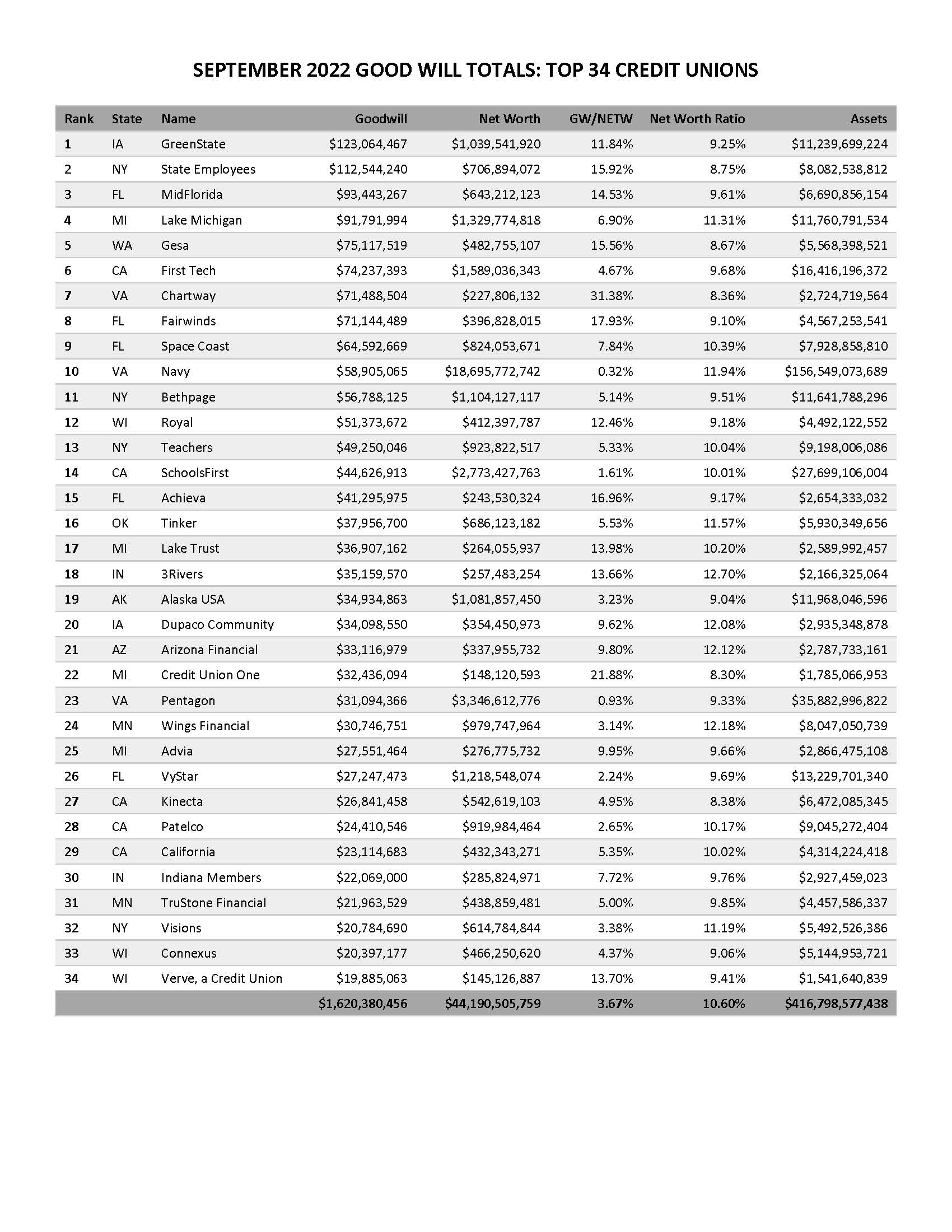

The following are the 34 credit unions (out of 277) with the largest amounts of good will at September 30, 2022.

The goodwill net worth ratio, column three, compares the size of this intangible asset to net worth. This ratio ranges from a high of 31% for Chartway to a low of .32% for Navy FCU. There is no regulatory limit on how high this percentage can be.

The goodwill net worth ratio, column three, compares the size of this intangible asset to net worth. This ratio ranges from a high of 31% for Chartway to a low of .32% for Navy FCU. There is no regulatory limit on how high this percentage can be.

While I do not know the details of every credit union listed, most of these goodwill leaders occur from either whole bank purchases or mergers with other credit unions. The first two names, GreenState and State Employees (NY) are examples of each activity.

The Regulatory Situation

As discussed in Part I goodwill is an intangible asset representing future economic benefits arising from assets acquired in a business combination, traditionally mergers or purchases.

It is not part of equity or retained earnings from a presentation standpoint.

Goodwill lacks physical substance. It is an accounting estimate based on assumptions used to project potential future value. Unlike mortgage servicing assets which are also an intangible, goodwill can’t be bought or sold.

If credit union A merges with credit union B which has goodwill on its books, credit union A receives no benefit. Credit union B’s goodwill is devalued to zero. It is not carried over onto credit union A’s books.

As the underlying benefits are realized, impairments to goodwill can be recorded. A credit union can also amortize goodwill over ten years. In both instances those charges flow through the income statement and reduce retained earnings.

In either option, all goodwill must be assessed for impairment at least annually.

Goodwill and Net Worth

For credit unions following CCULR: Goodwill is not part of Net Worth (numerator) for ratio purposes but is included in total assets (denominator) to determine the net worth ratio (NWR). Goodwill balances must be less than 2% of total assets to opt into CCULR.

For credit unions subject to RBC: Goodwill is a reduction from the RBC Numerator and also from the Denominator.

Goodwill Uncertainties

In corporate America public companies report over $4 trillion of goodwill on balance sheets, primarily from mergers and acquisitions.

While accountants agree on what goodwill is, how to value that goodwill after it’s passed onto the buyer’s ledger sparks plenty of argument.

There is much uncertainty about forecasting goodwill’s future benefit for a firm – it involves more judgement calls than many accountants are comfortable with. And while goodwill is listed as an asset on the balance sheet, is it really worth its stated value? What if it was a bad buy at an inflated price in the first place?

In June 2022 FASB announced it had given up on a four-year effort to simplify goodwill accounting determinations. The current annual impairment test remains the requirement versus a straight line annual amortization approach.

The Credit Union Goodwill Challenges

When creating goodwill, credit unions have all of the same accounting challenges as public companies but none of the checks and balances .

The ongoing difficulty is assessing post acquisition performance to see if it is meeting the values projected when the goodwill was first established.

In cooperatives this is made much more difficult because in both mergers and acquisitions, there is virtually no public disclosure of an acquisition’s costs let alone future projections.

For purchases, credit unions rarely report the total price paid(except when a bank is publicly traded) the broker and transaction fees, the future impact on ROI or ROE and the longer term performance goals to be achieved. For mergers, no details of a combined operational plan are provided just the asserted advantage of bigger size and more capital.

Most large mergers and whole bank purchases take years for operational and business integration to be fully realized. These transactions generally end relationships and market presence created from years of continuous service. That history and local advantage is now gone.

In some large credit union mergers a whole new corporate brand and identity are part of the combined entity’s future business plan. Shedding past connections to create a whole new market persona would seem to undermine a valuable legacy.

No Accountability

Credit union mergers and bank purchases are not market based transactions. They are private deals negotiated for mutual advantage by CEO’s and then announced to members. Because there is no transparency or numbers provided, little future monitoring possible.

Both transactions create goodwill but the credit union is playing with members’ house money. If the deal works out after three or four years, whatever benefits of expansion have been achieved are trumpeted as the result. If the bank purchase was overpaid, there is no stock price or performance metric that would highlight this misjudgment.

The bank owners are paid a cash premium for their shares from the members’ savings. They have left with cash in hand. If a transaction is poorly priced or managed, then the goodwill is written down from members’ existing capital.

The goodwill concept allows managers to pay premiums for purchases absent any performance goals. In a merger, goodwill in excess of book net worth just enhances the ongoing credit union’s capital but members receive nil for this value.

Transforming Goodwill Into Ill-will

When leaders operate in a closed environment, unconstrained by member or board governance, personal ambition can run amok.

With no meaningful credit union disclosures to members or the public in either mergers or bank purchases, managers are free to wheel and deal. A number of CEO’s have been very public about their “nonorganic” growth plans. Goodwill is the intangible asset created to make things appear OK regardless of price or terms.

The animal spirits of capitalism are quickly embraced versus the cooperative focus on members’ well being. But unlike truly competitive markets, there is no stock price or market assessments monitoring performance.

When goodwill accounts begin to approach 10% or higher of net worth, the credit union has disguised its ability to produce operating earnings. To keep the game going, more purchases and goodwill are pursued, always justified by scale and more diversification.

At some point the economy turns, the acquired assets become overvalued and members are given the short stick as dividends are reduced to keep up the ROA goals. In several of the credit unions listed dividend payments were reduced in 2022 versus 2021 to sustain ROA even though short term rates have risen by over 3%.

Staff layoffs are another indication of overcommitments. Examiners or accountants will start to question the goodwill asset’s value.

The goodwill that underwrites cooperatives can quickly turn to ill-will. When members realize their collective legacy in mergers was transferred to solely benefit senior managers, the loss of confidence will undermine both the new entity and the cooperative system’s reputation for fair dealing.

When the out of state or out of market bank purchase shows no growth, the tactic of buying market share begins to fail.

The facade of goodwill falls away for both the credit union and the members. Once gone, it is lost forever. That is what intangible means.