“The Ongoing Corruption of the Cooperative Credit Union System’s Ideals in America” (with edit updates on August 9)

I have previously observed that it doesn’t take an illegal activity to destroy a firm, an industry, or even bring harm to the broader economy.

I believe the credit union system is at a turning point. Since the passing of NCUA’s merger rule in 2017/18, the amount of asset takeovers (AKA voluntary mergers) has only accelerated. Some think this is a good thing. I believe numerous examples prove otherwise.

According to Credit Union Times the numbers are increasing. The majority of second quarter 2024 merged assets in this latest update have nothing to do with safety and soundness issues: The NCUA approved 46 mergers during the second quarter of 2024, up from the 26 consolidations that received the green light to consolidate during the first quarter and the 36 approved mergers during last year’s second quarter.

As discussed below some credit union CEO’s are “gaming” regulatory disclosure requirements to hide their significant personal benefits. Credit unions acquire sound, longstanding healthy credit unions through private deals which benefit and enrich the selling executive team. The members are given nothing but future promises and empty rhetoric, most frequently, “bigger is better.”

The transactions increasingly contradict any common sense understanding of financial equity or fairness for members. The information provided members and approved by NCUA is meaningless for any considered owner decision.

The cooperative system’s unique purpose and public reputation are at risk. These deals will be seen as just more of the same wheeling and dealing as for-profit banks. At some point these ongoing patterns of self-dealing will become the object of a business media story, a congressional inquiry or even consumer group action.

The good will and good works of the truly credit union spirited will be overwhelmed by the depredations of an ambitious few. The system may never recover from the consequences of these blatant examples of betrayal of the trust members placed in their “elected” board leaders and regulatory oversight.

In previous posts I have detailed cases from Exceed, Infinity, 121 Financial, Finance Center, and Vermont State Employees in which my analysis of the transactions made little or no economic or business sense-except for insiders. Members, who must vote any merger, have little or no power to object or even inquire. The process gives all the resources and media power to the incumbents initiating the deals. Member participation is presented as a purely administrative step because the regulators have “already approved the merger subject to the member vote.”

A current Example: Member One FCU transferred to Virginia Credit Union

In last week’s post, I describe the members’ “rebellion” against management’s proposal to transfer all the assets of the $1.7 billion Member One FCU to VCU. The opposition’s blog site was filled with multiple member voices against the change.

On July 30 after the vote closed, Member One announced the result: 3,479 voted to approve and 1,404 against. In the same release, the credit union stated it had become a division of VCU on August 1, or 24 hours after the vote.

Case closed or not? Certainly, the two credit unions want to give that impression. However It is important to seek the truth apart from these two “facts.” What other context is available about this event? Were the members’ best interests truly served?

My first observation: the voting participation seems extremely low for this controversial action. The number in favor of the merger, 3,479 is just 2.3% of the credit union’s 155,000 members. The total voters, 4,883, are only 3.2% of all eligible to participate.

This result means each Yes vote supported the transferred $474,000 of total assets and $44,560 of net worth to VCU. That outcome would itself suggest the need for greater scrutiny.

Why was the turnout so low? Were ballots sent to every member? How was the process managed? By whom? How does this member participation compare with other similar sized or contested mergers?

The Opponents’ Efforts

There was spirited public opposition including a news radio interview. The website Member One Vote No recorded over 80 member comments before being taken down. These concerns universally questioned the merger proposal. A Reddit link Member One Merger Cookies, is still active and provides a sample of the many comments in opposition.

Members posed multiple questions about the $570,000 bonuses being paid to the the credit union’s five senior executives. The members received nothing from their collective $155 million net worth and eight decades of loyalty.

The opponent’s Vote No site also included links to nine different VCU social media with postings by VCU members sharing multiple complaints about the acquiring credit union’s service, mobile banking, culture etc. Did Member One’s Board do any due diligence prior to announcing the merger in January 2024? If so, why was there no information about VCU’s business model or priorities, for example the reason for its recent decision to convert to a federal charter.

Twenty-Four Hours to End Member One’s Independence

My second question: why the rush to complete the merger in 24 hours after the vote ended, that is, by August 1? The Notice and FAQs clearly state “There are no anticipated changes to core services and member benefits. And, it will be 2026 before there will be operational integration. In the meantime, there will be two operational centers. No branches will be closed .

There are least two forms that must be sent to NCUA (6308A and 6309) both of which would take more than 24 hours, especially the combined financial statements, before a merger is finalized.

Why the speed to make this a done deal? The only effect is to remove Member One’s board and to give VCU immediate access to and full control of the credit union’s financial resources. Is VCU that much in need?

The very low vote participation and the rush to close the deal points to the need for more information about what is really going on.

The Responsibility of Credit Union Directors

There are two sets of board members who oversee each merger event. Member One’s board is very accomplished per their public resumes. From the June 2022 announcement of new board officers, the leadership team presents extensive professional and Roanoke community experience.

The Chair, Joseph Hopkins, signed the Member Notice of the merger’s required meeting. He retired from a long career at Norfolk and Southern, has been on the Member One board for over 30 years and is a 50-year credit union member.

Penny Hodge, Vice Chair, retired in December 2018 as Assistant Superintendent of Roanoke Country schools after 31 years. She is a CPA and became a Member One director in 2019.

A new board member in 2022 was Tyler Caveness who graduated from Harvard in 2014 with an economics degree. He is “founder and principal advisor at Caveness Investment Advisory, LLC, a boutique wealth management practice providing investment, income-tax minimization, and alternative financing strategies for the self-employed.”

Member One also appoints associate Board members. On May 23, 2023 the board announced three new associate members, all with excellent professional and local credentials. These are brief biographical excerpts in the announcement:

Armistead Lemon has an 18 year career in leading independent school education.

Mary Beth Nash is a local government attorney with 28 years experience representing private and public sector entities.

Rebecca Owens is Roanoke County Deputy Administrator, responsible for county’s financial administration and has 30 years in local government.

Why did these three experienced, Roanoke-based professionals support the ending of their local charter in a few short months after taking office? The merger announcement was on January 11, 2024. One presumes there was some preliminary discussion and due diligence by the board before this public decision.

It seems highly unusual these three experienced professionals would join an organization and then quickly turn around and support an end to their leadership role within just a few short months. What role did they play? What information were they given?

NCUA is very clear in its statements on the fiduciary role of directors. From two 2011 letters by NCUA’s General Counsel:

“we (NCUA)also believe that fiduciary duties are properly owed to people, and not to entities. FCU directors must understand the people who are affected by the directors’ decisions and identify which people the directors are serving.

“The danger is that, if the directors are allowed to focus only on the credit union when making a decision – without regard to how the members are affected – the directors can justify making self- serving decisions, or decisions that serve primarily the FCU’s insiders, under the guise that the directors are simply doing what is best for the credit union.” (emphasis added)

Failing the Members

There are no factual details or future commitments in the Member Notice that would meet this fiduciary standard for this merger. Let alone Directors’ duties of care and of loyalty. The only specific financial details are the bonus payments totaling $570,000 to five senior executives. Of this amount, $250,000 is due the CEO, Frank Carter, as of the effective merger date—which we now know was 24 hours after the vote closed.

Why did members receive nothing from their $155 million collective savings? In any other institutional sale in the open market, owners would have received 125% to 200% of their book value net worth. We know this because these are the routine multiples credit unions pay when buying banks. Should not credit union owners be treated as well as bank owners?

From the very general information in the four-page Member Notice, the widespread member opposition published in social media, and the explicit, immediate benefits going to the CEO and senior team, this merger seems contrary to any reasonable understanding of fiduciary responsibility by the board and executives of Member One.

They not only failed the 155,000 member owners but also the greater Roanoke community and the eighty-four year legacy of prior generations that contributed to creating this $1.7 billion local institution.

The Other Board of Directors: NCUA

NCUA’s rule 708b provides the process for the Agency’s monitoring and approval of every step of the merger process. The agency’s merger checklist has 21 areas for potential submission and seven required forms.

The update of the rule was announced during the GAC conference in February of 2017 in response to published examples of merger self dealing and outright solicitations. Chairman McWatters’ intent is quoted in this report of the merger landscape by Frank Diekmann in his CUToday analysis, Time to Talk About an Ugly Truth in Mergers:

McWatters: “The agency should diligently work to preserve small credit unions, as well as minority- and women-operated credit unions.

“In addition, the agency should require all merger solicitation documents to provide, without limitation, a discussion of any change-in-control payments and other management compensation awards and agreements, and that such disclosures are written in plain language and delivered to voting members in a reasonable time prior to the scheduled merger vote.”

Since that speech, and the passage of the rule Diekmann’s Ugly Truths have only gotten worse and disclosures minimized.

Member One’s merger is just the most recent example. No member owner, let alone an NCUA examiner, RD or board member could make an informed judgment about this merger proposal with the information in the four-page Member Notice.

If any credit union had provided this level of detail to purchase a bank or by organizers to start a credit union, the request would have been summarily rejected. Yet that is all the information credit union owners were given.

NCUA’s In Loco Parentis Merger Oversight

The impact of NCUA’s rule has been to put the agency’s judgement and fact review in the place of the members’ ability to make an informed decision. Most of the information required by NCUA in its 21 point checklist is not shared with members. For example, its review of the prior 24 months of board minutes are not disclosed along with multiple other filings.

NCUA then sends its approval of the Member Notice with its limited information which includes the date of the special meeting and ballots to vote. Absent are any of the details NCUA used to approve the application and Notice.

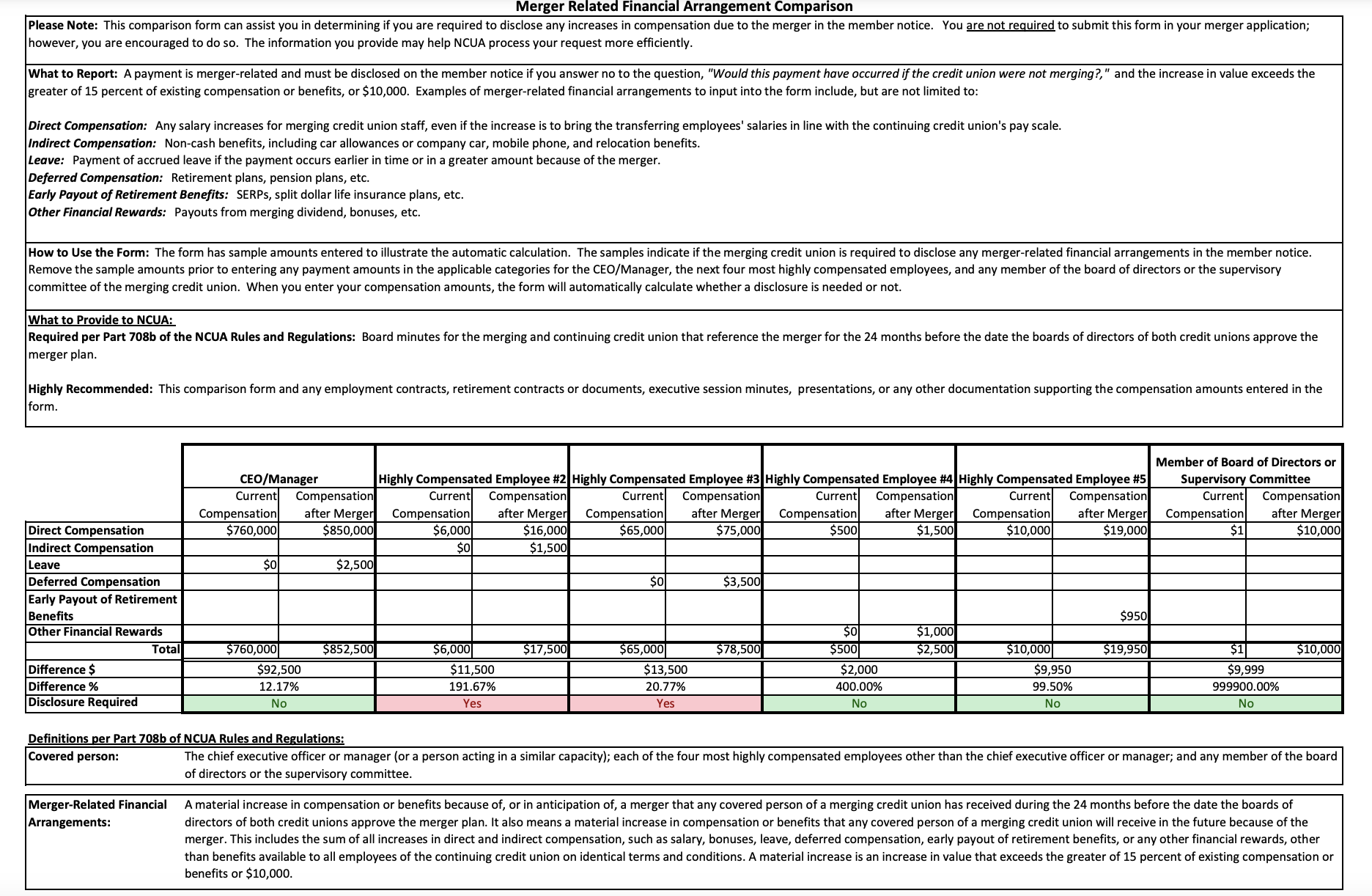

Moreover, the Agency has provided an easy work-around spreadsheet to help determine what must be disclosed, if anything, about compensation commitments. This is completely contrary to former Chairman McWatters’ statement of “without limitation” disclosures. In essence, NCUA shows credit unions how to “game” its own disclosure rule.

Self-dealing by those who lead the organization, oversee the entire process and control all resources to communicate with members was the number one priority addressed in the 2018 rule. Unlike state charters which must file IRS form 990 detailing board and executive compensation annually, FCU’s are not required to file or disclose any compensation data to anyone at any time.

The agency’s excel spreadsheet with sample entries helps to determine what portion, if any, of future compensation must be disclosed. Here is the form that credit unions can submit to show compliance or not, along with a required certification of No Non-Disclosed Merger-Related Financial Arrangements.

Future compensation is what the whole rule was intended to address, including conversions of previously funded SERPS and other benefit plans.

Why should NCUA be able to review this form, but not members? In the Member One Notice only merger related bonuses of $570,000 were revealed. However the credit union reported over $32 million in SERP and Employee Insurance Benefits in its June 2024 call report balance sheet that will either vest or be distributed under change of control clauses—but there was no disclosure of where those funds now go.

Reporting only merger related bonuses does not begin to reveal the compensation related commitments to senior employees in the merging credit union. Most will enter into new employment contracts with the continuing credit union that are guaranteed years into the future versus being at-will positions.

To illustrate this under reporting, NCUA recently approved a merger that disclosed to members only $900,000 of bonus or salary increases for the five senior employees. However, because the credit union was a state charter and the lengths of the new contracts were disclosed, the actual guaranteed payments were closer to $9.4 million for the highest compensated employees.

This is how the disclosures of self-dealing are “gamed.” NCUA has inserted its review in place of providing essential information to the members for their decision making. Members receive no facts, only rhetorical promises or future assurances. In Member One’s case, this motto was “Bigger is Better” an assertion easily contradicted by the diverse loan growth and ROA performances as of June 2024 reported by the top ten credit unions.

The Shortcomings Of the Merger Rule and an Easy Solution

There are two other serious information shortcomings in the merger disclosures. Nothing is required to be shown about the continuing credit union’s business model, priorities, plans or culture. In this case VCU’s social media posts suggest some potential cultural and operational issues.

If members are transferring the future management of all their assets to another organization, shouldn’t that organization’s plans and leadership intentions be part of the disclosures, even including the compensation of the continuing executives.

Voting by members in a merger is not about protecting their individual savings and loans. If members don’t like the outcome, they can withdraw and go to another institutions.

Rather the voting is about the transfer and full control of all the assets, tangible and intangible created in a credit union’s long history, to a third party. Now there is nothing required to be disclosed about the new organization’s taking over these accumulated resources except a summary balance sheet and income statement that is already available from call reports.

A second problem is that the voting process is deeply flawed. It has the appearance of democracy and one person one vote. In this case 97% of members did not vote on the future of their own credit union? Why?

Moreover, the entire voting process and institutional resources are in the hands of one party which has a vested interest in the outcome. Members who oppose have no way to easily contact other members, there are no resources for marketing or outreach. The credit union executives control all the messaging with its FAQ’s and in this case, free Oreo cookies.

This is not a democratic election process. It is a monopoly managed by those in power who control all the variables in the very short time frame in which the messaging and balloting is done. To end a charter should require a minimum number of members to vote, at least 20%, and provide a process for opponents to have access to members.

And the easy solution: Require every voluntary merger where the dissolving credit union has 7% net worth, to issue a public RFP for bidders and that there be a minimum of two proposals received.

RFP’s are a routine process in virtually every consequential credit union decision including technology choices and even the hiring of consultants who submit proposals in response.

NCUA should lay out the minimum RFP contents and then review the numerous responses. The credit union board has the data for why one option was chosen over another to recommend to members. Here is how the process works in a good merger.

The Apostates

The word apostates refers to someone whose actions or inactions, suggest they have totally abandoned or rejected their core beliefs or principles. Or maybe have no settled ones at all.

In this example of Member One’s executive suite and board’s professional credentials, the public record of merger disclosures versus the aspirations presented on the credit union’s website, all combine to give the impression these leaders abandoned whatever belief they had in their 84-year old credit union. Rather it was the members whose voices spoke up for the credit union while those in leadership sold out. (See one example at end.)

The role of NCUA’s three person board is also critical. What is their understanding of the cooperative charter? How is it different from banks, other than the tax exemption? What are the role and rights of member-owners? What does democratic governance, one person one vote entail, when board elections are rarely held? When only 3% to 4% of owners vote on the continuance of their independent charter, how meaningful is this process for mergers?

If the board believes the proper policy is letting the free market work its will versus setting regulatory boundaries, why is there no support for actual transparent market solutions? Why do bank owners reap rewards when bought by credit unions, but credit union owners receive nothing when control is transferred to a credit union third party?

Chair Harper, Vice Chair Hauptman and newcomer Otsuka have either turned a blind eye or have no problem with senior executives capitalizing on their positions for self-enrichment-and the members left holding an empty bag.

NCUA’s current board has taken no action on the growing number of examples where the fiduciary duties of all decision makers to protect members’ best interests have clearly fallen short of the clear standard presented by its General Counsel.

In the end this benign neglect will erode the financial and reputational foundations of the cooperative model.

Creating An Unsound Cooperative System

Ultimately this intentional or unintentional fiduciary abandonment by all parties will only spawn greater and greater incidents of insider sell outs in the pursuit of growth and greed. The result is more and more risk put into fewer and fewer baskets.

This increasing concentration decreases the traditional advantages of local relationships and stability and reduces overall financial and business diversity within the credit union system. The soundness of the system is narrowed; the variety of business models is reduced; and the traditional credit union advantages of local knowledge, control and earned loyalty are lost.

The unique design of democratic member-owned financial alternatives serving their communities faithfully over generations is sacrificed on the altar of bigness.

The cooperative model has been turned upside down. It no longer serves members interests first, but rather the personal ambitions of the institution’s leaders.

One Member’s Voice

When those in governmental or private positions of authority forget where their accountability is owed, the prospect of member rebellion grows. Who can forget the taxi drivers attending NCUA board meetings to lobby for member-focused solutions?

In the case of Member One, a person who served the credit union in leadership posted his logic for why this merger was not in the members’ interest on NCUA’s website. When posting comments NCUA “will review, redact and post submitted comments” and “also reserve(s) the right not to post a comment that we believe is false, egregious, or unrelated to the proposed merger.”

Sometimes we call these critics prophetic. When current leaders forget to whom their duties of care and loyalty are due, this comment presents a well reasoned, informed appeal for a return to core credit union principles.

The following is what this member “sees” versus what those in positions of authority choose to ignore:

I, Dwight Holland, MD, PhD STRONGLY OPPOSE THIS MERGER AT THIS TIME as a former 7 year Supervisory Committee Member of M1FCU, and 2 years as a successful Chair of that Committee. My background:

I was on the Supervisory Committee of M1FCU from 1996 to 2003, with the last 2 years as the Chair. So, I know what I am talking about regarding Credit Union matters.

I was also the guy that pushed hard in 1996 to get on-line banking into the Credit Union when some of our Board Members weren’t sure what a domain name was, or why we should do this. So, I AM NOT opposed to change and adapting when necessary or it makes sense for our members.

The reasons I am opposed:

1. We lose LOCAL CONTROL and influence in the governance of the Credit Union because we are being swallowed by a bigger fish. The smaller fish in the pond of merger always loses its identity, culture and influence with time, despite promises by the Board and CEO of both Credit Unions.

2. We are a HEALTHY, overall well-managed credit union that has grown to around 1.6 Billion dollars. Why surrender this LOCAL achievement and control to a financial entity in Richmond?

3. MemberOne started out as the N&W Credit Union, and grew with our own economy, mergers and healthy acquisitions of struggling credit unions in a non-predatory way. That rich history and legacy will disappear with this merger into the mists. As member number 4404 that started as a 6 year old, I personally don’t like that notion. I can see people in leadership, and talk to them directly, and they will listen. Having control going to Richmond will dilute that “personal touch” dramatically.

4. I am the Treasurer of a state-wide Military Organization that uses a national credit union (over 10 Billion in size) for its banking purposes. Trying to get help with such a large organization is just like dealing with a large bank. It is tedious to get anything done, when something doesn’t go well, it took me and national level leaders in our organization over 1.5 years to get a very simple, but critical thing settled. The larger an organization is, the harder it is to get through the layers of bureaucracy. Staff sometimes in large orgs just doesn’t “need” to care about you for their performance reviews. That’s not true for more locally controlled orgs.

5. As M1FCU member, we often give forbearance to our friends and neighbors regarding loans and the like if they as for it, and work with them to help. Larger, more distant Credit Unions, cannot, and generally will not do this to the extent that a well-run locally controlled one will.

6. There are more reasons not to merge that relate to insurances, benefits, control of wages locally, etc, but I’ll let others deal with those.

The “incentives (for executives) to stay” at the end of the meeting notice seem extraordinary – why is such an incentive needed? There would certainly be others available to hire who are well qualified should these people choose not to stay.

Well more than a half million dollars is being promised to these five individuals! That amount would best serve members in so many other ways: beefing up certificate and savings rates or assisting those who need loans, for example, would certainly serve the members better than this huge amount flowing into individual pockets.

I do not see numbers that benefit members of the credit union except those receiving incentives to stay. Respectfully, there is no way those employees are worth that much to stay. How much would the rest of the members receive to stay rather than to take our business elsewhere? I see no way this merger benefits the members except the 3 or 4 mentioned in the letter we received.