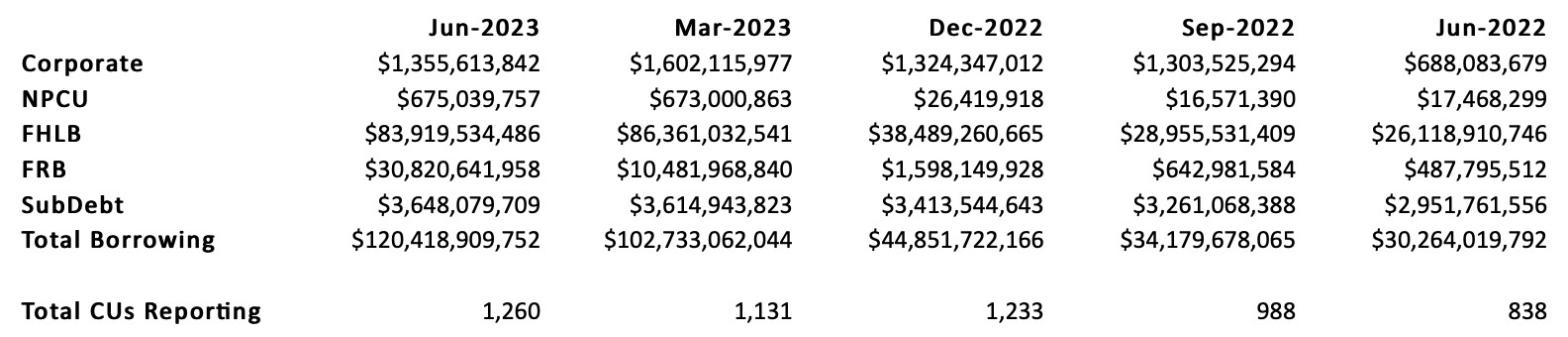

At the end of the September quarter, credit union total assets of $2.25 trillion were just 9.7% of total banking assets. However their participation in the special emergency Federal Reserve lending program equaled 27% of the BEFP’s loans at yearend or three times their share of total assets.

The September 2023 call reports show 307 credit unions with Federal Reserve borrowings of $34.9 billion, an average of $114 million. For these credit unions, the Federal Reserve represents 66% of their total borrowings. For 112 of this group, the Federal Reserve is their only source. The largest reported loan is $2.0 billion and two credit unions report draws of just $500,000 each.

In an ironical coincidence with the BTFP participation, this total was also 27% of all credit union borrowings at the quarter end of $130.3 billion. Moreover this $35 billion was only a small portion of the reported $173.4 billion in total lines these credit unions had established with the Federal Reserve.

Most of these loans were drawn following the banking liquidity crisis in March. The Fed created the emergency Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) after the Silicon Valley Bank failure to prevent a system wide run by uninsured depositors on other depository institutions.

This facility was different from traditional Federal Reserve programs. Eligible collateral security was expanded, all collateral was valued at par, not market , and draws could go up to one year. The rate for term advances under the Program is the one-year overnight index swap rate plus 10 basis points. The rate is fixed for the term of the advance on the day the line is drawn down.

What Happens Next?

In a January 9, 2024 speech to Women in Housing the Federal Reserve’s Vice Chairman for Supervision, Michael Barr, was asked about the program’s future when the initial one year life is over. Here are portions of his reply:

Moderator: I wanted to ask you about the future of the BTFP. We are rapidly approaching the one-year mark, is this something where the Fed is planning on extensions, or any information to be released to the public on usage?

Vice Chair for Supervision Barr: So when the funding stress happened in March 2023, over the weekend the Federal Reserve, FDIC and Treasury agreed to a systemic risk exception to least cost resolution for the FDIC. And the Federal Reserve and the Treasury worked together to create an emergency lending program for banks and credit unions, the Bank Term Funding Program that you are referencing. And the Bank Term Funding Program enables banks to use collateral that was in place as of that time – as of March of 2023 – that is, essentially Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities, to pledge those, and to be able to get borrowing against that up to a year at the par value of those securities.

That program was really designed in that emergency situation. It was designed to address what in the statute is called unusual and exigent circumstances – you can think of it as an emergency. . .we want to make sure that banks and creditors of banks and depositors of banks understand that banks have the liquidity they need. And that program worked as intended. It dramatically reduced stress in the banking system very, very quickly. And deposit outflows which had been very rapid in that short period of time normalized to what had been going on before and in fact maybe flattened out to some extent a little bit.

So that program was highly effective, banks and credit unions are borrowing under that program today, but it was really set up as an emergency program. It was set up with a one-year timeframe, so banks can continue to borrow now all the way through March 11 of this year. . .a bank could continue to borrow or refinance under the program and in March of this year have a loan that then extends to March 2025.

I expect continued usage until that end date of March 11, but it really was established as an emergency program for that moment in time.

Arbitrage Opportunity Grows Outstandings

Two days after Barr spoke, the Wall Street Journal published an update on the program: Banks Game Fed Rescue Program.

The article reported that the BTFP pricing, based on the benchmark interest rates average plus 10 basis points, was less than the 5.4% the Fed was paying on overnight excess reserves. This arbitrage opportunity has resulted in an increase of $12 billion in more drawdowns since yearend even though no liquidity strains were apparent in either system.

Credit unions can request extensions up to one year until March 11, 2024. After that date, the statement above and the most recent activity suggest the program will end. Credit unions should plan to either repay or tap other sources of liquidity.

And the CLF?

It should be noted that the Central Liquidity Facility reports no loans this year as of its November financial statements. In fact it has initiated no new loans since 2009. The BTFP participation suggests credit unions certainly have liquidity needs. However the CLF, designed to serve and funded totally by credit unions, is not as responsive as the Federal Reserve Banks.