This post is a eulogy. For 36 years credit unions were provided a comprehensive report on their collective progress. That publishing effort grew in scope, analysis and detail while keeping the same title: The Credit Union Directory. It is no more.

The Credit Union System’s Essential Resource

In 1986 Callahan’s introduced the first complete Directory of all active credit unions for the industry’s and general public’s use. It was a complete census by state of every credit union, a task never accomplished in the eight decades since the first charter.

One reason for this gap was there was no centralized source for information. NCUA’s call report included only federally insured data. There were approximately 1,800 cooperatively insured credit unions in over 20 states that offered a choice of share insurance.

Prior directories were periodically attempted. One listed the 4,000 largest credit unions by assets. Some state leagues published listings, but they were not for public use.

A Calling Card

The Directory was Ed Callahan’s idea. At great expense, Callahans had established a database of all NCUA data, augmented with cooperatively insured information. We believed the industry and public would beat a path to our door for the latest, most complete data on credit unions.

The company had an outstanding invoice for over $100,000 with a local service bureau that managed the information. No one came knocking. Ed decided we needed a “calling card” to let people know about our analytic capability. Hence the first Directory, with 1985 data listing every credit union, was released at the February 1986 CUNA governmental affairs conference.

The initial product was a literal directory organized by state listings in credit union alphabetical order. The single line of information with the credit union was the CEO’s name, contact information and summary financial data: total assets, loans, members and capital.

As the Directory became an annual effort, the content expanded. Advertising was added to support production costs. The concept of a one stop information resource became widely valued. At least three other competitors entered the market: NCUA printed and gave away a state listing of its insured; Thompson’s added a credit union volume to their bank and S&L publications; and CUNA attempted its own version.

All subsequently dropped their “directory” efforts. For Callahan’s, this calling card expanded with more analysis and industry listings. It demonstrated the firm’s software capabilities that eventually led to the development of Peer to Peer as the premier industry analysis product.

Annual Publications: The 2006 Example

The listings remained central, but the annual analysis expanded in multiple ways.

New reference material was included to give added value and market reach. For example, the top 100 Canadian credit unions were listed in the belief this might open up a northern market. It didn’t. World Council information was presented showing the US totals in a worldwide context.

An example of this ever expanding effort is the 2006 edition which totals 646 pages in four tabbed sections.

Each year, the Directory’s cover was redesigned. A theme summarizing the movement’s progress was introduced . In 2006, the message was Communities United by the Cooperative Difference.

The first tab, State of the Industry, presented the industry’s consolidated balance sheet and income statement, key trends and auto loan share by state; 30 “best in class” leader tables; an analysis of the corporate network; a listing of CUSO’s, credit union auditors, leading technology providers and a list of mergers. Contact information for all state and federal regulators, leagues and trade associations and Canada’s largest 100 credit unions were provided in just the first 125 pages.

Tab two was the traditional listings provided by state. Each state was headed by a five year performance summary and a top 50 by assets table preceding the alphabetical list of all the credit unions. Seven pages were devoted to comparing state by state performance on key ratios.

The third tab was a cross reference listing where a user could look up credit unions alphabetically by name, by city, or by the manager’s last name. For example, seven Carlsons and 65 Johnsons. Buffalo, NY, reported 42 credit unions with home offices in the city; Carmel, IN, had just two.

If one wanted a quick summary of credit unions by employment, the reader could look up credit unions that had Post Office or Postal, IBM, State Farm as a first name. Or, if looking for parish-based credit unions, one would find 185 credit unions whose name began with St. (Agnes, et al ).

The final section was a buyer’s guide which showed 115 vendors serving the credit union community. And helped to underwrite the Directory’s printing costs. The sponsor for 2006 was Charlie MAC. For those not familiar with US Central, this was a secondary market initiative for credit unions to compete with the government sponsored GSE’s.

The Incalculable Resource

Each edition attempted to list the major system components and the businesses serving credit unions. To address concerns about timeliness of the data (publication occurred about 4-5 months after the financial information), Callahans in 2006 created a “Directory Online” with 24/7 access. This digital version was updated with the latest financial as well as contact changes.

By publishing annually, the industry had a comprehensive set of performance benchmarks in one volume. Who had moved in or out of the top 200? How many credit unions have home offices in DC? Or, what states have the fastest growing coop system? While the information was at a point in time, it was a starting place for limitless stories and analysis, then or in years later.

Leaving the Scene

Callahans last annual printed Directory was volume 36, published in 2021 using December 2020 data. This edition had 221 pages including a 29-page buyer’s guide.

There was industry analysis with ten-year trends, leader tables, and peer group comparisons. There was still a state-of-the-state section in which all the individual credit unions were listed. Contact information was also provided for CUSO’s, Corporates, regulators, and trade associations.

There was no introductory analysis or theme, undoubtedly hindered by the Covid lockdown and recovery during the production cycle.

In 2022, there was no printed edition. The industry trends, top 50 or 100 listings, the corporate network and state summaries are available online. If printed, the information would total 132 pages. There is no advertising or buyer’s guide.

Does It matter that there is no longer a printed Directory?

There are certainly virtual substitutes for some of the data listings and contact information. One can search on NCUA’s site for peer information and trends. Pulling other categories of information (CUSO’s, trade associations) would require someone with a knowledge of relevant resources. If interested in a year’s key industry events such as large mergers, charter conversions, bank purchases, or even newer data sets such as subordinated debt or goodwill, one would have to find a credit union database resource such as Peer to Peer.

The Directory’s function expanded assembling performance and individual credit union data to serve as a starting point for insight and analysis. At a macro level, the Directory was the only source for ten-year financial trends and a two-year balance sheet and income statement that includes all credit unions, not just NCUSIF insured.

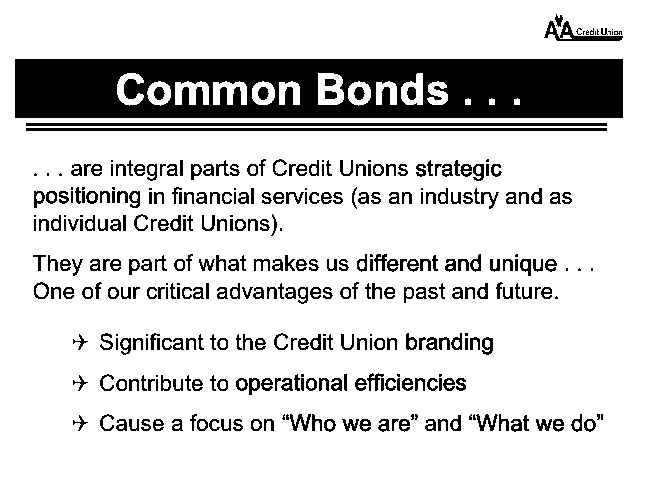

But the Directory was more than a useful compilation for quick reference. It presented the industry’s multiple connections and comprehensive participants. Each volume was a census of all key movement participants (by name and organization) and an almanac of the year’s trends.

Each edition presented the collective industry’s performance, information missing from all other yearend reports. For example, NCUA’s Annual Report records its activities and financial audits, not credit unions’ role in the economy. Trade groups report their advocacy, education and information services. Individual credit unions promote their own success and accomplishments.

What is lost is the sense of cooperative identity, a shared destiny and a system with special purpose that serves over 100 million member-owners. If one were to understand the history of the credit union system, especially the post deregulation era, the Directory would be the major resource.

This bridge connecting the past to the present no longer exists. Each future writer or researcher will have to find their own way to the history.

The Directory memorialized multiple national, state and local milestones for a movement whose future should be more consequential than its past.

Without this collective benchmarking, can there be a shared purpose? If one fails to celebrate birthdays, anniversaries or other key events, life goes on. So will credit unions but with less of a sense of who they are and where they have come from.

A movement without a collective memory can slowly disintegrate into individual contemporary stories. The shared destiny is lost as firms follow their own independent journey. A Community United by the Cooperative Difference no longer has a record of who they are.