A CEO reflects:

“It is an honor to comment on a wonderful man who has been the most influential mentor in my career. Rex taught all of us the unique way of being significant in individual lives. At Utah First, you see Rex’s influence in every employee. We don’t judge members; we look for the opportunity and good in every relationship. Bad things can happen to good people and we try to look beyond the moment and provide the chance for everyone to be their best. This is Rex to his core. We will miss our dear friend but find comfort that he lives in all of us each day.”

– Darin Moody, President/CEO, Utah First Credit Union

Rex’s Entry into the Credit Union Story

In 1979, the Illinois credit union system was at a critical turning point. The 1,035 Illinois charters was the largest of any state. Wisconsin at #2 had 633 charters.

Illinois charters served over 1.4 million members and held 7.2% of all state-chartered assets in the country. In August 1979 a recodification of the state’s credit union legislation (first passed in 1925) was approved by the legislature to respond to the onrushing disruptions in financial markets and the economy ushering in the era of deregulation.

Short term Treasury bill rates spiked in 1979 at over 15%. Disintermediation of deposits from the regulated rates paid by depository institutions was redistributing consumer savings into unregulated money market mutual funds.

In addition to this unprecedented rise in short term rates, labor strikes directly affected many of Illinois’ largest credit unions. There was a 58-day strike at United Airlines in the spring. In the fall, almost all of the farm implement companies saw labor shutdowns—first at John Deere plants, then Caterpillar Tractor locations, followed by International Harvester work sites.

At the end of the year, Chicago’s school system troubles caused payless paydays for the teachers and their credit unions. Eight of the state’s largest 15 credit unions served members who had been on strike, faced layoffs or were suffering from the economic slowdown.

Key Illinois Credit Union Trends

Of the 1,035 charters, only 56% (580) had NCUA insurance. Share growth at 6.4%, was half of the 1970 decade’s 12%. Members earned on average 6.8% on savings and borrowers paid 10.9% on loans. Loan rates were capped by a 12% usury ceiling. Average capital was 7.6%. Delinquency rose to 3.2% at year end.

Lending portfolios were almost all consumer loans. Regulations required credit unions to have over $1.0 million in assets to make real estate loans or issue share drafts. Of the 310 above this asset threshold, only 23 reported real estate loans. They totaled $66.2 million, or just 3.7% of all $1.8 billion loans outstanding. In this same asset group, only 49 credit unions offered share drafts which amounted to just 1.7% of all member savings.

The system’s loan to share ratio stood at 93.5%. Rules limited unsecured loans to a maximum of $5,000, secured loans to $20,000 and real estate loans to $50,000. Credit cards were nonexistent for most consumers from any financial provider.

Illinois federal and state credit unions combined reported total members of 1.5 million, or 10.3% of the state’s total population of 11.3 million. However, these 1,477 credit unions provided 13.5% of the state’s consumer loans, just behind the 15% share from consumer finance companies. Credit unions’ share of the deposit market was 4.2% compared to 30.4% for banks and 65.4% for thrifts.

The Personnel Upgrade

To respond to these seismic changes in financial services, the Credit Union division’s annual budget was $633,000, entirely funded by exam and supervision fees from credit unions. The division’s Chicago and Springfield offices employed 32 personnel including 22 field and review examiners. The division conducted a surprise exam and a full exam for every credit union. To set contact priorities, the semi-annual call report was automated. Credit unions were sent the same financial five-year Financial Performance Report examiners were given to monitor trends

Other division activity, including administering 25 mergers, 13 liquidations and 3 new charters during the year, plus implementing a landmark recodification expanding credit union powers and upgrading regulatory oversight.

That was the “day job.” The division’s managers spoke at trade association events, chapter dinners, CUES training conferences, attended a minimum of seven Advisory Board meetings and two “Days with the Director,” one upstate and the other down. Nationally, Illinois became an active member of NASCUS. I was the first state regulator chosen for the newly formed Federal Financial Institution Exam Council (FFIEC) coordinating the implementation of truth in lending legislation. The division followed the establishment of the NCUA’s CLF. Caterpillar Employees Credit Union was the first borrower to use this new cooperative liquidity option.

A critical priority for Ed Callahan, Director of the Department of Financial Institutions (DFI), was upgrading the performance of all field and professional staff. In the credit union division, CPAs were hired to supervise field staff and all examiners were required to have or obtain accounting credits. New managers were recruited from outside government to supervise the Chicago and Springfield Offices.

This is when Rex Johnson entered the credit union story.

The ad in the professional job listings in the Chicago Tribune was for the Chicago Office Manager of the Credit Union Division of DFI. The position’s requirements included an undergraduate, preferably an MBA degree, and management experience in banking or finance.

Rex met none of the listed criteria. No college, no finance courses. Just a dozen years making and collecting mostly unsecured consumer loans, working his way up the hierarchy of Household Finance Corporation (HFC & “Friendly Bob Adams”). His performance in multiple branch assignments in North Carolina and Virginia earned him a promotion to run an HFC’s branch in Chicago near the company’s headquarters.

Rex passed on the DFI ad. However, his wife Connie urged him to apply because he enjoyed managing people. She believed the prestige of working for the State would enhance his professional opportunities.

The DFI’s general counsel Bucky Sebastian initially interviewed Rex, outside business hours at a 24-hour diner, to avoid jeopardizing Rex’s HFC career. Was his asserted capability “for real?” It was. When I talked with Rex, so persuasive were his answers, I hired him with one condition: that he get a degree–as part of DFI’s program to upgrade the professional skills of all staff.

Rex immediately looked into night school to get an undergrad BA. He did not find that option appealing because much of undergraduate coursework had no direct job application. We then met with the Dean Vennie Lyons of Northwestern’s evening MBA program (in which I was enrolled) to see if Rex might qualify. Dean Lyons while open to the possibility, also suggested Rex consider Northwestern’s new Executive MBA program which offered a more structured and traditional academic model.

This “executive” program targeted mid-career professionals working full time with weekend meetings in a class size of 25 who would learn together for the entire 2-year program. Each class was admitted as a group with a common curriculum. Lyons said the program might consider one or two “high risk” applicants in each class from persons who did not meet the normal academic and experience requirements. Rex was accepted, received his Masters in Management (MBA), and years later told me, “it was the hardest thing I ever did.”

While Chicago supervisor, Rex brought his lending insights to help examiners and also added a special capability when instances of fraud were uncovered. Most wrongdoing involved key personnel, often the CEO, in smaller shops. If not tracked and resolved quickly, the future of the credit union could be jeopardized as most small credit unions were run by few employees.

When an examiner found false accounts, unreconciled bank statements concealing theft, or other misappropriations, the agency’s job was to restore sound operations rapidly. Most credit unions had no share insurance. The fidelity bonding company was reluctant to pay quickly for “unfaithful performance” claims without full evidence of the loss.

Upon receiving the examiner’s findings Rex would go to visit the suspected bad actor. His goal was to persuade the person to cooperate to quickly resolve the situation. The best way to do this was to obtain a written statement outlining what the person had done. He would explain that by confessing their errors, a person could be at peace with their conscience.

He succeeded every time. With the signed document in hand, the credit union’s board understood the need for new leadership and the bond company responded quickly upon receipt of the state’s exam findings and written confession. The credit union could continue normal operations and avoid being bogged down reconstructing records to find which accounts and transaction were false or real.

Moving on to Baxter as the Founding CEO and Spreading the Lending Gospel

In 1981 Director Ed Callahan delivered a new charter to Baxter corporation which wanted to provide credit union benefits for their employees. Later the company’s executives asked Rex to interview for the CEO’s role of starting the credit union even though still lacking a college degree. He was chosen to organize this new charter startup, a processing taking over a year. As CEO he grew the organization to over $ 300 million in 1994 when he left to become a full-time lending consultant starting his own firm.

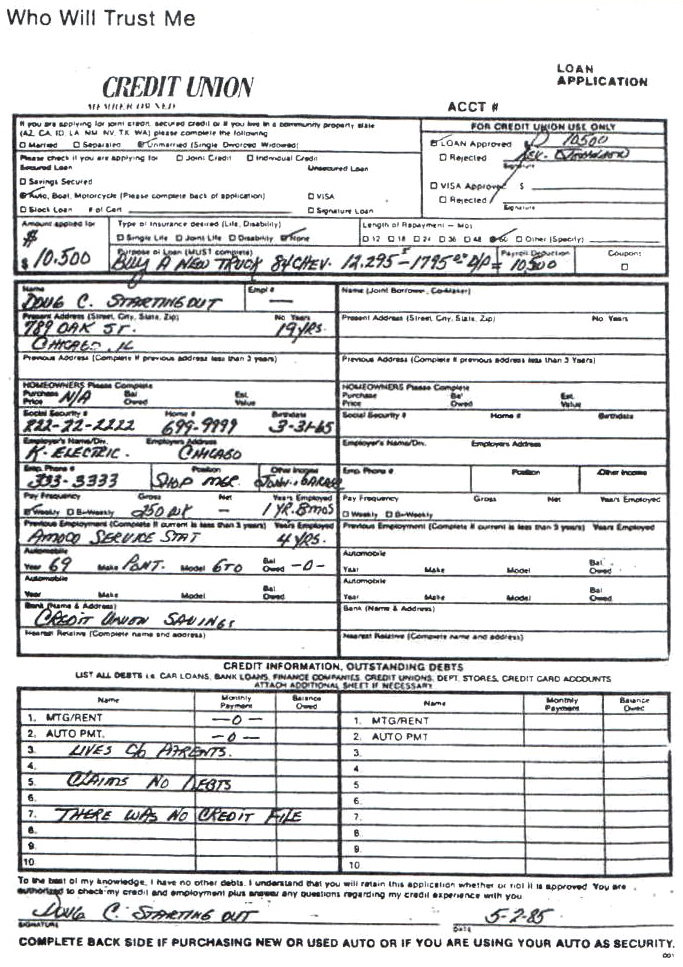

By experience and conviction, Rex believed the most important activity of a credit union was making loans. He brought his years of hands-on lending and collections from HFC to promote lending as an “art,” not merely filling orders. The “art” required learning a person’s whole story to understand their character, the basis for sound credit judgment. Always look for the good, not for reasons to turn down a loan, he would later tell students.

While growing Baxter as a lending machine with a loan to share ratio at 85% or higher, Rex spread his gospel into the broader credit union community. He even worked with NCUA to produce a special edition for the agency’s Video Network showing examiners how to evaluate loans.

He wrote lending case studies for the monthly Callahan Report addressing all aspects of loan decisioning and oversight. The titles summarized his main point: “Don’t let Ratios Turn Loans Away,” “Five Focal points of Every Application,” or “Get control of Your Decision making.” In September 1988 Callahan’s and Rex coproduced a Special Lending Workshop, called, It’s Time to Fight Back-–Increase Loans, Stop Bankruptcies and Inspire Staff.

These cases studies and loan management skills became the basis for Callahan’s publishing, A Passion for Lending, and its sequel, More Passion for Lending. The cases were drawn from the dozens of credit union consulting projects Rex completed on weekends while still CEO at Baxter Credit Union.

In February 1994, he left Baxter (now BCU credit union) to form Lending Solutions, Inc and devote the rest of his career to helping credit unions better serve members diverse borrowing circumstances.

His Skill as Teacher and Preacher

While continuing to do individual credit union consulting, he converted his observations into five-day workshops called the University of Lending. Loan officers, CEO’s and even directors would attend.

A key to the success of these week-long workshops was that attendees worked with real loans from their own credit union. not just Rex’s vast collection of cases.

In these classes, Rex would do live phone calls using recent turndown examples from attendee’s loans, to show how an apparently “unqualified” applicant could be prudently helped. Once done, he would close the call by saying, “Now that I have helped you, if you would like me to assist any of your friends or family in a similar situation-just have them call me at this number.” He would then hang up the phone and predict he would receive callbacks within the hour. He normally did.

He would also do live collections calls in the class. He would often get an answering machine and would leave a message, asking the borrower to call him saying, “I have great news for you.” When an attendee asked what the great news was, Rex would say, “I won’t know until I have talked to them when they call back.”

These high wire live performance demonstrations helped convince credit unions that they too might adopt Rex’s approach. That is, everyone has a story, find out their circumstances, and look for the good. Before Rex’s teachings, loan staff were often taught to be “order takers,” responding only to the member’s request, and overlooking many other ways a credit union could improve the member’s financial life.

Rex honed his lending skills in the trenches. He was always willing to put his words into practice. Before visiting a credit union, he would ask them to send a sample of 20-30 recent applications including turndowns, charge offs and newly approved loans. Out of these small samples he could create concrete examples showing ways credit unions could better serve members and make the credit union financially stronger. His ability to demonstrate his approach created believers who were frequently hesitant to change long standing policies endorsed by examiners.

Rex had high energy and was competitive. In the first five months in his own business, he consulted with over 100 credit unions. He worked seven days a week pushing himself and seeking the same effort in his colleagues.

At Lending Solutions, he developed all channels to spread his wisdom: publications filled with case studies, videos, webinars where attendance might exceed 1,000; the 20 or more week-long in-person University of Lending programs each year; individual credit union loan consulting and workshops on the road; and a joint venture to establish a 24-hour call center so credit unions could outsource lending decisions after hours, during peak periods or for other support calls.

An Evangelist Who Believed Credit Affirmed Members’ Hopes

Rex’s life captures many qualities of the iconic American spirit of the self-made person. He had no advantages of personal circumstance. Moving from one opportunity to another he believed in the power of word of mouth. He was his own best salesman while convincing others they could do the same.

Credit unions were a fertile environment for his many talents. His passion was lending because it gave people hope. Every member he believed had some good credit points even when recent history might suggest otherwise.

He entered the industry when credit was extended based on character or the credit union’s often advantaged position with payroll deduction or being tied in with a member’s employment. As consumer lending accelerated after deregulation, the process became more controlled by policy parameters, FICO scores and automated response fulfilling members’ requests.

Rex put the member back at the center of the lending decision. Document why you made the decision, he would say, not that you followed policy. His cases and videos are still relevant today.

But an even greater aspect of his legacy is the tens of thousands of credit union employees and directors who attended his multiple events. These students have undoubtedly helped millions of members benefit from Rex’s lending gospel.

In a recent Zoom call where his passing was announced, some reactions marked impact:

- He taught you to go deep and understand each person’s story.

- I attended his lending school and then sent all my loan officers-it changed the way we loaned.

- You can see a spike in our lending level after our annual training sessions, and it stayed.

- We set up a requirement that any loan decline had to be reviewed by a senior manager; (Rex believed 80% of credit union turndowns were fundable)

- He changed our mindset; he was one of a kind.

- Rex’s training brought humanity into lending; strongly supported C and D applicants.

- Eye-opening. He showed us that lending is a judgment business.

For the thousands who knew Rex personally and experienced his presentation gifts, all would agree that he put the “credit” back in the “credit union” story. Every member should be grateful for that reawakening.

Two “Cases” Highlight Rex’s Influence

With all of his lending skills, story-telling and positive spirit, Rex’s success came from an instinctive insight about people: everyone’s need for mutual connections to feel fully valued. His lending philosophy recognized this compelling human reality—the same motivation that causes individuals to organize credit unions in the first place. It is as simple as “people helping people.”

Rex believed case studies were the most effective means of showing his lending philosophy. Following are two personal accounts demonstrating this ability to inspire individuals.

His Last Engagement

Dana Garrett. President/CEO

North Memorial Federal Credit Union

I hope it is okay to reach out via email. I feel more articulate in writing than verbal, especially in light of the loss of someone so impactful to both our industry and my personal career path. My voice still tends to quiver when remembering and talking about someone I was lucky enough to call a mentor and friend.

Rex Johnson is the person I credit with turning my “job” as a green New Accounts rep into a career- moving all the way up into a credit union CEO role. Many years ago, Rex, on a consulting visit to our $70M credit union in Colorado, told my CEO I was wasted talent behind a new accounts desk. As a result, I was one of the first to be given the opportunity to attend Rex’s University of Lending school in Illinois.

Rex’s passionate interpretation of the movie Patch Adams and its application to credit union member services appealed to me and brought home the philosophy of “seeing what no one else sees.” This philosophy has followed me throughout my 25-year career in credit unions.

In my current credit union, this is most evident in the creation of our BIG PICTURE LENDING program. We believe our members are more than their credit score. We work to understand their full story and provide relief where many have been turned down. We have seen credit scores improve and members who felt they may never qualify for a mortgage now realize the dream of home ownership.

Rex’s philosophy is engrained in our lenders and all credit union staff. We knew that to provide loans to higher risk borrowers we would need buy-in from the top down. So we engaged Rex to speak to our Board and staff at a team building event. It would be the last engagement he agreed to, according to Scot Vackar at Lending Solutions. Our entire team at North Memorial FCU became instantly bonded to Rex, his dynamic and unforgettable personality as well as his philosophy. His loss has been felt across our entire organization.

Our industry has lost a pioneer and the void will be impossible to fill. His legacy will live on in Lorrie as well as Ed, Jack, Bob, Scot and the entire team at Lending Solutions. His many U of L graduates will continue to be ambassadors for his work and belief in credit union members.

There is part of me that still believes I am doing what I am doing because Rex “saw what no one else saw” in me. J

He Was My Patch

Kara Reno, Loan Officer,

CSE Federal Credit Union, Canton, Ohio

Thank you for reaching out. Where to begin? A sentence or two would just not be enough. He was my friend, my mentor, my cheerleader. To say he will be missed is an understatement. His being placed in my life was one of the best things that has happened to me.

Over 16 years ago was the first time I attended one of his schools. We all know Rex teaches a little differently. The first part of the day is watching the movie Patch Adams. He stops the movie at pivotal parts that he feels should be highlighted and are important to help you think differently, live differently, work differently. To see what no one else sees. Then the 2nd half of the day is textbooks and numbers.

When I got back, I presented the CEO with what I thought we should do. I was so excited I couldn’t talk fast enough. I was flipping through my notes, reading him quotes, and telling him my ideas faster than he could process what I was saying. He told me he would think about it. The next day I went back into his office again to see if he was done thinking about it. I told him we have to do this, trust me, I know it will work, please let Rex come here and talk to the board, let’s change what we are doing, give it a chance.

It worked!! We did this, Rex did this, success!! A success for our credit union and our community. I will miss his lectures to me about how I made a difference, telling me I’m special, how smart I am, and most importantly telling me I’m one of his favorite people…..He will always be one of my favorite people too. The person always in my ear telling me “you did this, you made this happen, you changed people’s lives for the better.” The person that NEVER let me down. Over 16 years of some of the best times, conversations, and memories. I will miss having him around to believe in me. I will miss Rex.