This week NCUA will report on the 2023 financial audit of the NCUSIF in two days. This will be the 42th external, independent certified audit of the fund.

The Good News: A Ratio Showing the Fund’s Stability

Multiple financial events have presented numerous stress tests for the NCUSIF since 2008. These include 2008/9 Great Recession followed by quantitative easing and a period of abnormally low rates. Then came the COVID national economic shutdown. The current inflation has been countered by the Federal Reserve’s rate increases, the most rapid in 40 years.

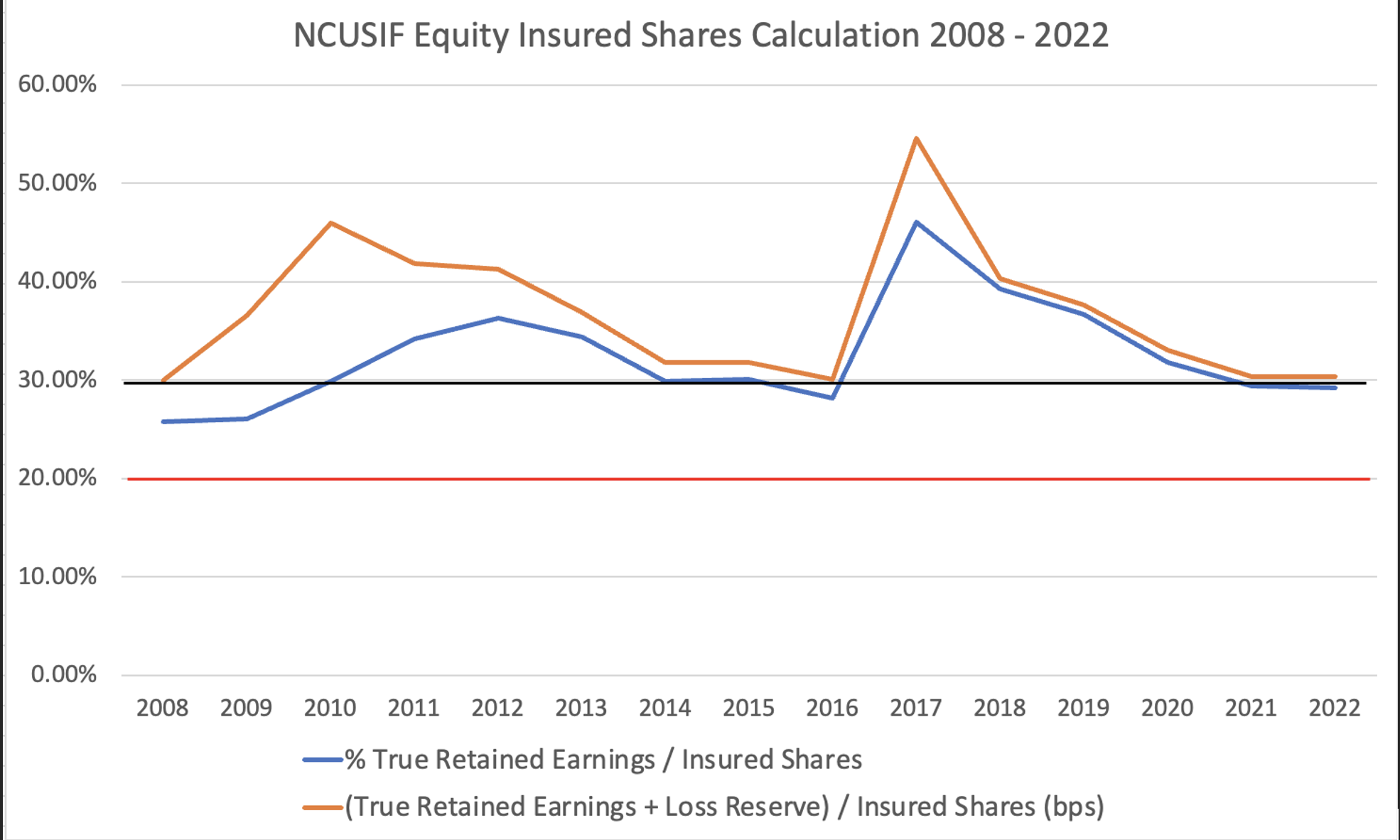

Through all these scenarios, one trend line demonstrates the Fund’s resilience. The chart below is the ratio of retained earnings to insured shares for this 14-year period.

The blue line shows the Fund’s equity at or above the historical .3% upper cap. The orange line adds the allowance account balance, which are additional reserves already expensed from equity.

The uniqueness of the fund is more than a steady earnings base growing in tandem with insured risk.

This cooperative funding model aligns with the values, culture and balance sheet structure of the credit union system. Every member contributes 1 cent of every $1 share for this collective insurance. In turn it is a resource available to assist any credit union that needs cash or other 208 assistance if facing insurmountable challenges.

The unique NCUSIF design works; however the history may not be known to current board members or to some credit union leaders. Credit unions need to remind all of this important story and what this stability has meant for their members.

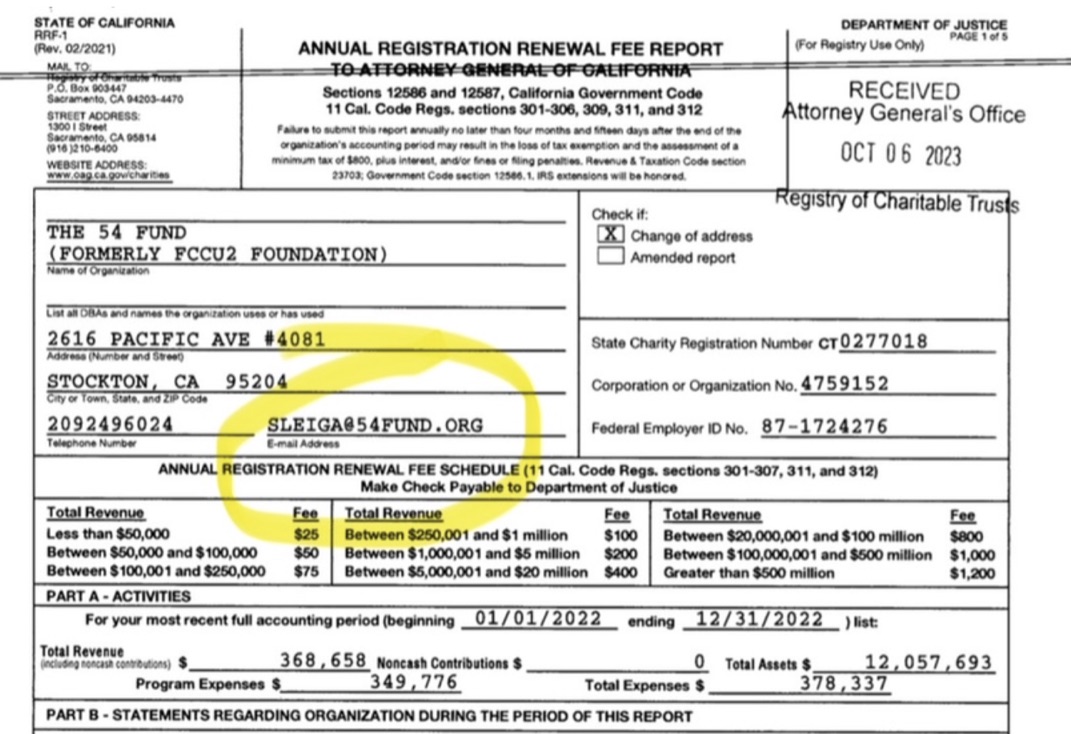

The NCUSIF’s Founding-Getting the Correct Numbers

Outside audits were not the practice from the NCUSIF’s founding in 1971 through 1981. GAO had performed an audit every two years; the report came six months or more after the audit date. The 1982 NCUSIF Annual Report described this change from GAO to a private independent firm implementing GAAP accounting standards:

“To ensure the Fund’s statements are examined in the most timely manner and to seek an assessment of accounting procedure, the NCUA contracted for the first independent audit ever conducted of the Fund’s balance sheet by an outside accounting firm.

In the years prior to fiscal 1982, the Fund recorded losses from financially troubled credit unions at the time these credit unions were ultimately merged or liquidated. Additionally, losses on asset guarantees . . . were recorded at the time that payments were made under guarantee agreements.

Beginning in 1982 the Fund began the process of conforming its accounting for losses from credit unions to GAAP. (These) principles require that the fund record losses at an earlier point in time than had previously been the Fund’s practice. In this respect the Fund recorded estimated losses under the cash assistance program of $14.1 million and of $15.6 million on outstanding asset and merger guarantees.

In addition, GAAP generally required that the Fund record estimated potential loss accruals for credit unions identified as experiencing financial difficulties but not receiving cash assistance. . . The Fund did not attempt to estimate these additional losses for fiscal 1982 because it was not practicable to accumulate the information needed to make the estimates.

Equally as important as the change in accounting methods were the improvements to the fund’s records. Ernst & Whinney worked with the Fund’s accounting staff identifying areas that were not properly recorded . . . As a result the Fund is now publishing monthly statements which will help all interested parties monitor the financial results.” (pages 7-8 NCUSIF 1982 Annual Report)

The Report’s remaining 20 pages gave details of cash assistance, guarantees and merger costs along with an overview of all insurance programs and credit union trends. Transparency in every respect was essential for confidence in the Fund’s management.

Chairman Callahan’s view was that, “We believe our “full and fair” disclosure should be no less than what we expect insured credit unions to give their members.”

A Radical Change in Accounting Accuracy, Timeliness and Transparency

In the 1984 audit, Ernst & Whinney gave the Fund its first ever clean opinion “in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles applied on a consistent basis.”

Without this three-year effort (1982-1984) to improve the timeliness (monthly board reports), accuracy (GAAP accounting) and transparency, the credit union system might not have supported the radical redesign of the NCUSIF. This new approach required perpetual 1% deposit underwriting.

This cooperative model was passed by Congress in 1984 with full credit union support. To implement the 1% underwriting, 15,303 federally insured credit unions deposited $845 million into the fund by January 1985.

The Last Shall Be First

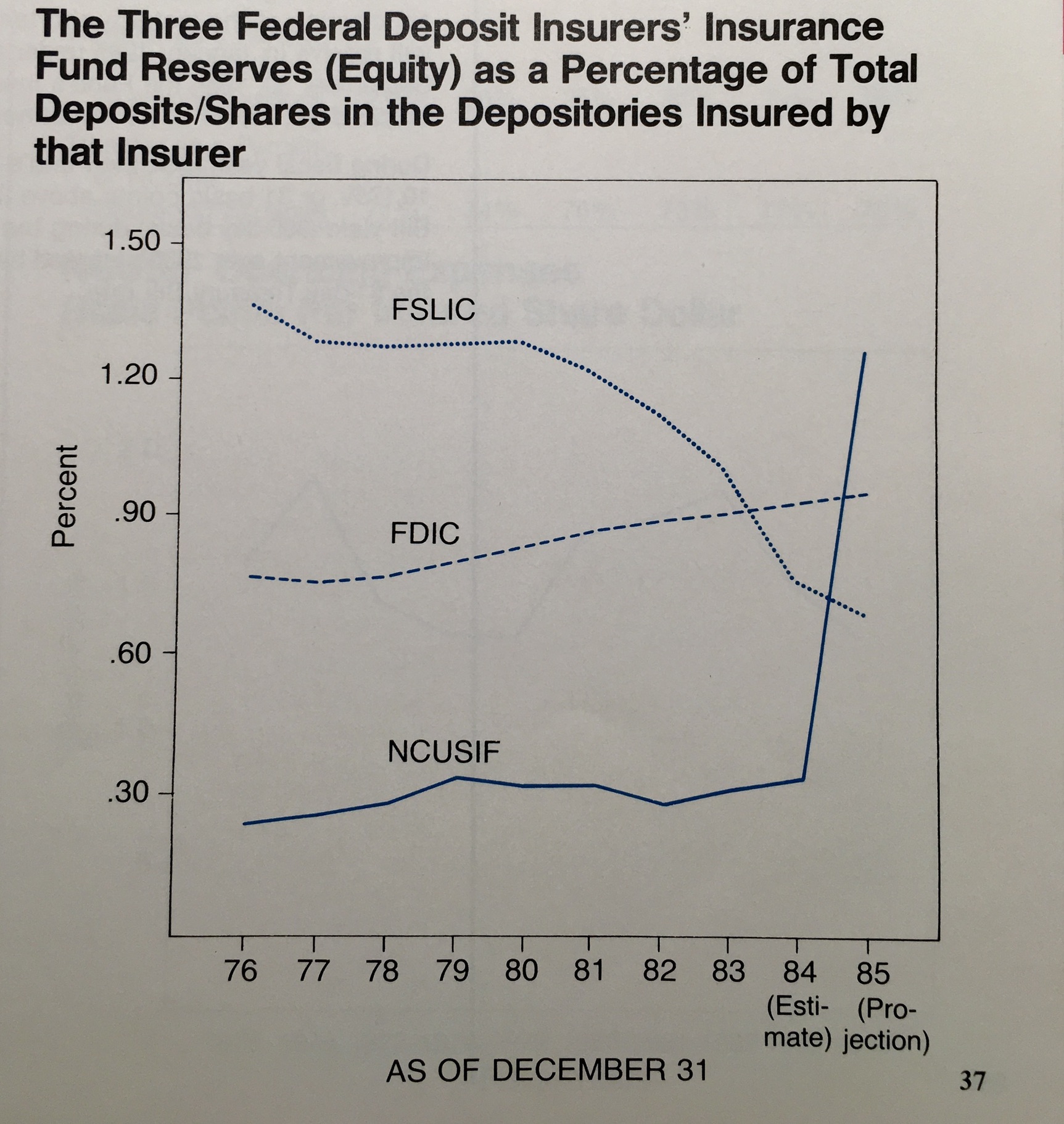

The result was that the NCUSIF instantly became the strongest and, through time, the most stable of the then three federal deposit insurance funds.

The NCUSIF never looked back or across the aisle. The FSLIC merged with the FDIC. The FDIC has reported negative net worth and periods of ever increasing premiums, such as now, to try to meet its minimum ratio level.

NCUA’s graph of this change in the standing of the three funds from page 37, NCUSIF’s 1985 Annual Report.

Vigilance-The Price for Performance

In a speech to credit union managers and the press following the 1984 recapitalization, Chairman Callahan gave the following “pitch”(his word):

“Don’t set it up and forget about it. It’s unique. It’s a better way. But just as important, it’s yours to monitor—it’s your responsibility to keep it working—because if you don’t it’ll go just like everything else the government touches. When government gets more money, it wants to spend more. Our goal is to spend less (on insurance). You’ll have to hold us to that promise.”

Then in 2010 there came a change in how the NCUSIF’s financials were presented.

The Change In Accounting Standards for the NCUSIF

The NCUSIF’s GAAP presentation was a financial format that all credit unions knew and followed. This GAAP audit is the only format used in NCUA’s Operating Fund and the CLF since they were both audited by independent accounting firms beginning in 1982.

On June 23, 2010 Credit Union Times printed a story with the headline, Auditors Fault NCUA’s Accounting. The article in part:

“KPMG gave the NCUA an unqualified audit but found material weaknesses in the reporting and documentation methods. . . NCUA Chairman Debbie Matz said the 2008 and 2009 audits (released on June 14, 2010) had been delayed because of the problems facing the corporate credit unions. . . According to the KPMG report, the NCUSIF does not have sufficiently comprehensive policies and procedures that document control activities and monitoring functions that should be embedded and/or performed within the financial and reporting process.”

In a June 17, 2010 Agency bulletin, the NCUA board announced it had adopted Federal GAAP accounting for the newly authorized TCCUSF. The same bulletin had this statement:

The National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF) is required by the Federal Credit Union Act to follow U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The General Counsel’s opinion concluded that “section 105 of the GCC Act, as interpreted by the General Accounting Office, does not preclude NCUSIF from using an alternative set of accounting rules such as FASAB in preparing the NCUSIF’s financial statements.”

Shortly thereafter there was a change as reported in this footnote in the NCUSIF’s 2010 yearend audit: Basis of Presentation The NCUSIF historically prepared its financial statement in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) based on standards issued by FASB, the private sector standards setting body. On September 16, 2010, the NCUA board authorized the NCUSIF to adopt the FASAB standards for financial reporting, effective from January 1, 2010. Accordingly, this is the first year of the presentation of the NCUSIF financial statements in accordance with FASAB.

A Misleading Accounting Presentation

However, FASAB’s form and content are very different from private GAAP. The account titles, presentation and interpretation are intended for reporting entries that rely on governmental funding. The NCUSIF is totally dependent on credit union funding. The FASAB format is completely alien to the accounting presentations familiar to and used by credit unions and CUSO’s.

A Strange Set of Federal Accounts

Some of the NCUSIF’s balance sheet accounts that are completely novel under federal GAAP include:

Balance Sheet headings and account categories: Intergovernmental. With the public; Insurance and guarantee program liabilities;(Loss reserve); Net Position, and its cumulative results of operations (not the same as retained earnings)

The traditional Income Statement is replaced with two other presentations. The first is, “Statements of Net Cost”. This includes Gross Costs followed by Less Exchange Revenues and concludes with a bottom line Net cost of Operations (which is not net income).

The second Statement is Changes in Net Position. This includes net unrealized loss or gain on investments, and interest income, the primary revenue source for the NCUSIF.

In standard GAAP, Statements of Cash Flows is replaced with the governmental “appropriations terminology”: Statement of Budgetary Resources. This includes subtotals for Total Budgetary Resources, Status of Budgetary Resources and Outlays Net.

These accounting concepts are far removed from any of NCUSIF’s actual operations. When staff gives the board’s NCUSIF quarterly update, it converts the income and balance sheet statement to the traditional GAAP format. However the monthly postings are not converted. They remain in the idiosyncratic federal GAAP Accounting format.

Understanding Critical Accounting and Finance Decisions

The NCUSIF’s federal presentation is misleading in its factual representation of transactions which suggests that the NCUSIF is a governmental appropriated fund.

Certain critical concepts and terms are absent. The most important is “retained earnings.” One looks in vain for the number which is used to compute the NCUSIF’s normal operating level. Another concept is “fiduciary assets” which means AMC assets are not fully recognized on the NCUSIF balance sheet.

The NCUA Board’s Opportunity: Enhance Transparency for the Fund’s Users

Eternal vigilance is hard when numbers are presented in a federal disguise. At a minimum, the NCUA board should request the auditor also represent the yearend audit numbers in private GAAP format. Staff should also present the monthly updates in this standard.

Then users of the statements can easily understand the trends. More importantly they can fulfill the challenge from a previous NCUA chair for credit unions: it’s yours to monitor—it’s your responsibility to keep it working.

Restoring easily understood transparency to the NCUSIF’s financial presentation would be an important step forward for the NCUA Board in its upcoming annual review.