In NCUA’s 1982 Annual Report Chairman Callahan’s opening Foreward presented his approach to the Agency’s priorities:

“One year ago we were in the midst of a dialogue with credit unions about deregulation. . .our sense was that government was doing too much. In the name of safety and soundness, we the regulators, had become overzealous. . .

In acting to change this direction, we were not advocating that credit unions should “do something” . . .Instead we tried to give credit unions self-determination . . .we tried to get out of their way. Government can’t react quickly enough to allow credit unions . . .to remain competitive.”

In every speech Ed reminded: “Deregulation is not freedom. It is responsibility.” To a NAFCU conference he stated: “I think the vitality (in credit unions) comes from the initiative and ingenuity of the individual boards. Hopefully they’ll all do it differently so that the country’s eggs are not all put in the same basket. “

Reexamining FOM “Groups”

After NCUA approved the total deregulation of share accounts in April 1982, attention focused on the agency’s interpretation of the FCU Act’s common bond definition. Callahan described this review in the Annual Report :

“Traditionally the agency viewed that “groups” meant an occupational credit union would be one sponsor, one employer period. Groups within a well-defined neighborhood, rural district or community meant 5,000 people, then it meant 25,000 people; then we weren’t sure how many people it meant. But numbers were all it meant.

“We believe that this very narrow interpretation was probably far more insidious than the rules and regulations promulgated over time. We have taken a more liberal view. We think that if the law does not say no, it certainly leaves room for yes. . . And so we think this interpretation is a far more deregulatory action than doing away with rules and regulations.”

Ed looked at the full scope of credit union history. Open charters were present alongside more restrictive common bonds. The practice in Rhode Island for example, was that their state charters could apply for statewide authority to serve anyone who lived, worked, or worshiped via a bylaw amendment. Many states had much more responsive FOM interpretations than NCUA allowed.

The result was that beginning in 1982 federal fields of membership became more flexible through senior clubs, multiple group charters and allowing members to select from multiple credit unions, that is overlapping charters.

Still today, federal FOM changes are much more deliberate than most state processes. NCUA common bond oversight has metastasized as a vestige of bureaucratic control. Numerous vendors including former NCUA employees still offer consulting services to help credit unions seeking FOM change.

The Context for Callahan’s Reappraisal

Ed’s belief in the importance of deregulating the common bond was shaped by his life experiences. These include his thirty years as a teacher and administrator in the parochial school system; his six years overseeing the Illinois credit union system as director of DFI; and his belief in the unique self-help possibilities of cooperative design.

In Illinois there were almost 1,100 state charters in 1977 when he became Director. He saw first-hand the challenges of unprecedented short term double digit rates. The old economic and regulatory order was passing; the need to change how credit unions responded to their members was urgent.

For example in 1978 Sangamo Electric Credit Union in Springfield lost its sponsor when the company moved to Georgia. I was credit union supervisor and said the law required that we close or merge the credit union as it no longer had a sponsor.

Ed’s reply was: “The company moved, not the people. They need their credit union now more than ever.” We changed the credit union’s FOM so it could continue serving members.

In these initial years at DFI we saw how government regulation and process at all levels had become so slow and bureaucratic that the members, the people credit unions were meant to help, were the last to be considered.

More Than an FOM Interpretation

In his speeches Callahan called the credit union system a “sleeping giant.” He believed that all Americans should have a cooperative financial option.

During his tenure as Chairman, field of membership flexibility was just one aspect of credit union expansion.

New chartering efforts were encouraged with universities and colleges a point of emphasis to bring the next generation into the movement.

In November 1982 a group of credit union leaders met in Philadelphia to plan CUE-84. This stood for Credit Union Expansion. The goal was 50 million members by the 50th anniversary of the FCU Act in 1984. The honorary Chairman was NCUA board member Elizabeth Burkhardt. In addition to the presidents of national trade associations, leagues and NCUA staff, the committee included the credit union CEO’s of Navy, United Airlines and the president of CUNA Mutual.

Spreading the word about credit union opportunity was more than an FOM change. It was the belief that helping grow members was in everyone’s and the country’s interest.

FOM: Inclusive, not Exclusive

Before deregulation, the public impression was that one had to be a member of a sponsoring company, association, or church to join. That was often the case. Ed wanted to turn that traditional view upside down.

He believed credit unions should be inclusive, not exclusive. As he was often quoted,”I do not believe in THE common bond. I believe in a common bond.” That “a” was the responsibility of each credit union’s board and management to define and serve.

Many Different Frames- One Goal

Today there are as many practices of the common bond as there are credit unions. The FOM is like the frames in the National Gallery’s thousands of paintings. Every picture, every frame is different. That diversity is the credit union system’s strength.

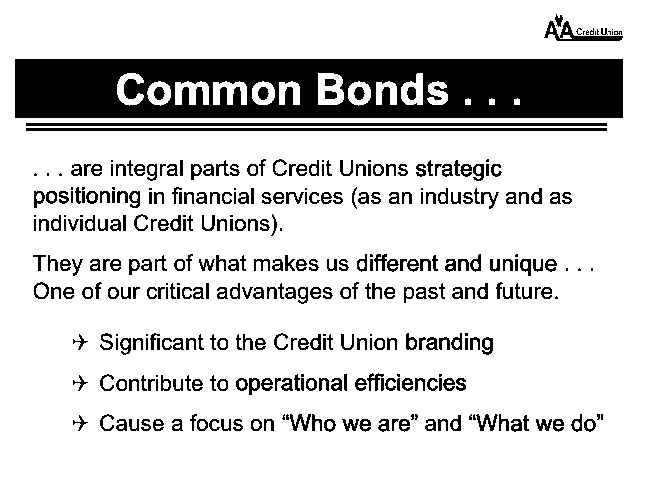

To see the common bond as an advantage or not, is to misunderstand the core of credit union success.

Credit unions are a prime example of the “relationship economy.” We all connect in our lives with some group(s) to fulfill a sense of purpose. As human beings we aspire to join together in productive, self-fulfilling ways. We rely on others and they depend on us.

Credit unions are one option. When led well, they become much more than “just a job.” Or when members use the phrase, “my credit union,” more than a financial alternative.

Ed believed in credit unions as a community just as John Tippet stated in his 2001 speech to Navy Federal.

Ed’s lifelong leadership of multiple organizations demonstrate the special skills required to build “communities” of shared purpose. The FOM should be a building block for credit unions, not a regulatory stumbling block.

Fields of membership are a “frame” for credit union performance. What occurs, the painting within the frame, is what makes each credit union unique.

.