The radical, cooperative redesign of the NCUSIF was approved by the NCUA board in October 1984.

In this board meeting video excerpt, Chairman Callahan thanked all who had worked to put this new “safety net” in place. He called it a “great victory that is truly unique and sets the credit union system apart from all other financial institutions.”

Board member PA Mack stated his support of the new plan: “I think this is an outstanding product as a partnership among government and credit unions. “

Chairman Callahan closed with these words about what it would take for this redesign to succeed: “The real challenge now goes to the people at NCUA. The system can work beautifully for credit unions in the future. . . the real secret now is the operations.”

This look back suggests the wisdom of Ed’s insight. For the unique structure is only as effective as the people responsible for its implementation.

Immediate Success Brings Temptations

In NCUA’s 1985 NCUSIF’s Annual Report, the board led by Chairman Roger Jepsen reported that in the first year the restructuring had “returned over $275 million in tangible benefits” to credit unions. (Page 5)

The major initial concern was whether the agency’s multiple supervision efforts to resolve problem situations could reduce the losses charged to the fund. The 1985 Report reported five-year trends that documented losses for all liquidations at only 1.5 basis points of all credit union insured savings. Net losses in closed credit unions were $3.1 million, the lowest in the previous five years. The fund’s $29 million dividend at yearend was a payout ratio of 46% of net income. The Fund still maintained its 1.3% equity ratio.

But the fund’s fourfold increase in size, revenue, earnings and financial success also resulted in changing the long-standing practice of how the agency’s operating costs were allocated to the NCUSIF. From 1981 through 1985, this allocation had ranged from a low of 30.5% to 34%. This ratio aligned with the percentage of state charted credit unions insured by the NCUSIF.

At yearend 1986, state charters were just 33.3% of all NCUSIF insured institutions. However the NCUA board increased the indirect expense to 50%. As stated in that year’s Annual Report “The cost of these services which totaled $16,821,936 and $8,069,244 for the years ended September 30, 1986 and 1985, respectively, are reflected as a reduction of the corresponding (operating) expenses in the accompanying financial statements.”

The NCUA’s operating expenses charged to FCU’s “declined” from $21.5 million in 1985 to $17 million in 1986. This 100% increase in the NCUSIF’s expenses reduced the operating fee paid by federal charters. There was no change in the proportion of state chartered credit unions covered by the NCUSIF. This was an easier political option than raising the fee charged FCU’s.

This 50% increase in the expense allocation highlighted the most frequent concern expressed by credit unions about the new plan. Here are some questions asked at a Q & A open meeting about the plan as reported in NCUA’s 1984 Annual Report:

Questioner:

What if the fund doesn’t operate on the interest earned? If you don’t pay a dividend? What happens if the agency is poorly run? (pages 18, 19)

The concern was specific. If the agency was given more money, wouldn’t it just be tempted to spend more? Could the agency change the guardrails at its sole discretion?

This 50% increase in the Overhead Transfer Rate (OTR) was just the beginning of efforts to use the increased resources, not for insurance costs, but to underwrite the ever expanding agency budget.

“Building Out” The Agency

Soon after the 1986 OTR adjustment, the NCUSIF became the funding source for the NCUA’s building aspirations. In 1988 the Operating Fund “entered into a $2,161,000 thirty-year unsecured note with the NCUSIF for the purchase of a building. . .In 1992, the Fund entered into a commitment to borrow up to $41,975,000 in a thirty-year secured term with the NCUSIF. The monies were drawn as needed to fund the costs of constructing a building in 1993.” (NCUA 2003 Annual Report pg 52.)

The variable rate on both notes was equal to the NCUSIF’s prior month yield on investments. The interest was paid by the Operating Fund, 50% of whose expenses were then charged back to the NCUSIF. The NCUSIF loaned the money and then paid half the interest on the loan!

It should be noted that during this construction and move to a new building in Alexandria , VA financed by the $42 million loan, the NCUSIF still paid a dividend every year from 1995 through 2000, as the fund’s yearend equity ratio was above the 1.3% cap.

A Double Whammy in 2001

The Fund’s financial management which had produced six consecutive annual dividends was altered in two significant steps in 2001 by the NCUA Board.

The first was to increase the percentage of the fund’s OTR from 50% to 66.6%. This resulted in a 37.3% growth NCUSIF’s operating expense while the operating fund reported a 31% decline in expenses in just the first year of this change.

The operating assessment for FCU’s fell by 20.4%. The NCUA board was able to lower this fee on all FCU’s by shifting the expenses internally to the NCUSIF funded by all credit unions.

Each year since 2001, NCUA has calculated a different OTR’s based on “a study of staff time spent on insurance-related duties versus supervision-related duties.” This ever fluctuating OTR peaked at 73.1% in 2016 under Chairman Matz.

During the past two decades of variable OTR, the percentage of state chartered credit unions in the NCUIF has remained more or less constant. At June 30,2022 the 1,811 stare charters were only 37.3% of all FISCU’s.

The second administrative action was more consequential, because it modified how the normal operating level (NOL) was calculated and thus when the dividend is required. In a footnote 5 to the NCUSIF’s 2001 audited financials the following change was announced:

The NCUA board has determined that the normal operation level is 1.30 % at December 31, 2001 and 2000. The calculated equity ratio at December 31 was 1.25%. The equity ratio at December 2000 was 1.33% which considered an estimated $31.9 million in deposit adjustments billed to insured credit unions in 2001 based upon total insured shares as of December 31, 2000. Subsequently, such deposit adjustments were excluded and the calculated equity ratio at December 31,2000 was revised to 1.3%.

The Fund reversed its year earlier NOL determination. But even with this retroactive adjustment to the December 2000 equity ratio, the footnote continued: Dividends of $99,490,000 which were associated with insured shares as of December 31, 2000 were declared and paid in 2001.

Since the 1% deposit redesign in 1985, this annual adjustment has always been collected in the following year. And until this 2001 modification, the retained earnings/equity ratio was based on yearend insured savings. A dividend was paid if retained earnings exceeded the .3% cap.

By not counting the 1% true up until the amount was billed results in an understatement of the actual NOL. It eliminated a dividend in years when the ratio would have exceeded the .3% cap under the prior practice, starting in 2001.

The Ultimate Guardrail Change

Since 1985, the NCUSIF normal operating level (NOL) had always been set at 1.3%. In many years the cap was not reached, but the resulting ratio was considered adequate even if under the cap. During and after the Great recession, the Board did not change the 1.3% cap even though they had been authorized to do so in the 1998 CUMAA.

Then in 2017 the board voted to merge the surplus from the TCCUSF into the NCUSIF. But this surplus would have raised he NOL to greater than 1.5%. To retain this amount above the traditional 1.3% cap, the board took two actions. It raised the cap to 1.39%, the first time this change had ever happened.

The agency also immediately expensed and added to loss reserves $750 million from the TCCUSF surplus to pay for potential losses in natural person credit unions. This action directly contradicted the congressional language establishing the TCCUSF that the fund “was not to be used for natural person credit union losses.” But it did reduce the NOL to 1.39% even after setting aside a dividend for credit unions from a portion of the surplus.

This was the first time that the cap had been raised above the longstanding 1.3 level. No verifiable details were provided about how this new level was determined except for summary data unsupported with actual calculations.

NCUSIF Success Raises Temptations

Credit unions’ concerns about supporting a perpetual 1% underwriting were well founded. Their worry was “If we send more money to the NCUA, won’t they just be tempted to spend it because that is what government does.“

Subsequent NCUA boards have converted the “partnership” understandings referred to by Board member PA Mack into a perverse interpretation: that to “protect the fund” the agency has to spend more and more on its operations to accomplish that objective.

From 2008 through 2021, the NCUSIF spent $2.2 billion on operating expenses and only $1.88 billion on actual cash losses.

NCUA has converted the fund into the agency’s cash cow. It has transferred much of its annual budget increases to the NCUSIF. For example in 2012 the operating fund expense was $90.6 million; six years later in 2017 the expenses were still only $90.3 million All of the annual increases in the agency’s operating budget and more, in this six years, were paid by the insurance fund.

Federal credit unions became “free riders” as the operating fee paid an increasingly smaller share of the agency’s expenses.

The NCUA Board’s Responsibility: A Legacy Being Squandered

While staff proposes, the board disposes of their recommendations. NCUA and its budget are literally exempt from any outside approval. The agency is independent. This absence of oversight raises responsibility of political appointees.

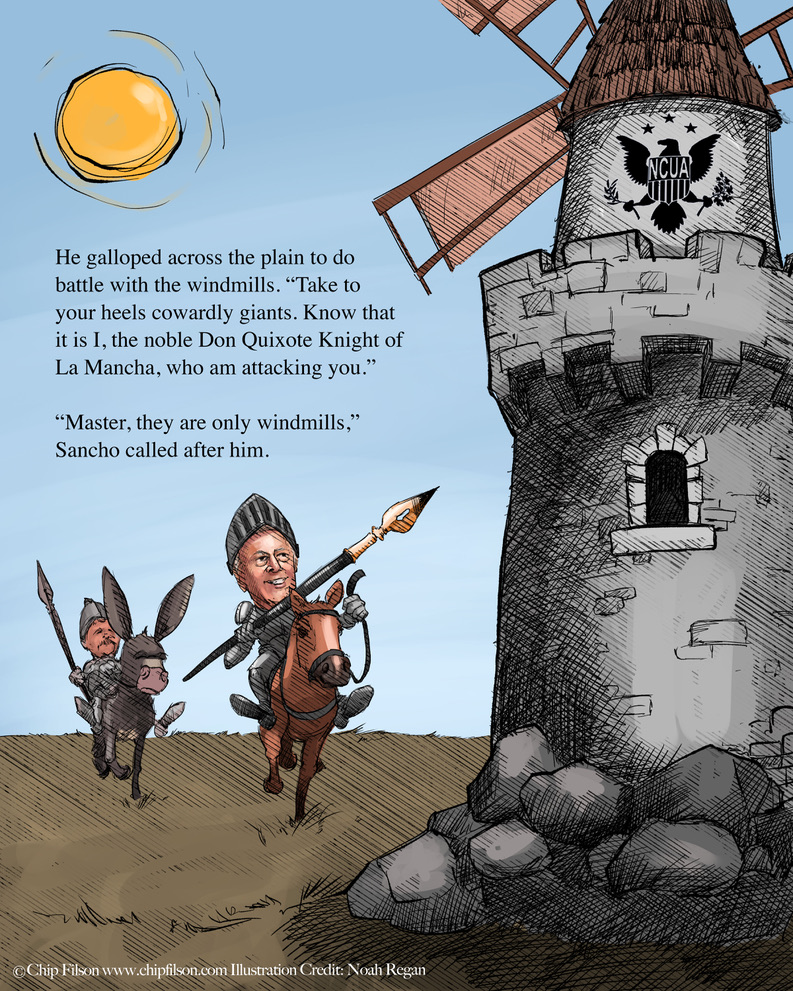

The annual OTR transfer have lost any connection to insured risk. Instead they remind one of a person declaring their waistline to be 32″; but then, when you gain weight, redefining 32″ as whatever your waistline happens to be. Insurance activity is whatever we want it to be.

The shortcomings have been bipartisan. Republicans and democratic appointees have repeatedly affirmed transparency and actions to protect the fund. But in practice the agency has declined to release the accounting options provided by its own outside CPA firm Cotton, the details in setting its annual NOL limit above 1.3, or the investment options and risk analysis used in managing the fund’s portfolio.

Every NCUA board member inherits a unique cooperative legacy in the NCUSIF that requires both knowledge and diligence if the fund is to be sustained. This responsibility takes work and continual vigilance.

When the critical guardrails of the fund are modified one by one, the initial signposts of success are forgotten, and critical facts routinely omitted, then the prospect of a sound NCUSIF future is undermined.

The most important success factor in the Fund’s special public-private partnership is the ability to ask hard questions. When this is not possible for board members to do and to followup, then it is up to credit unions or Congress.