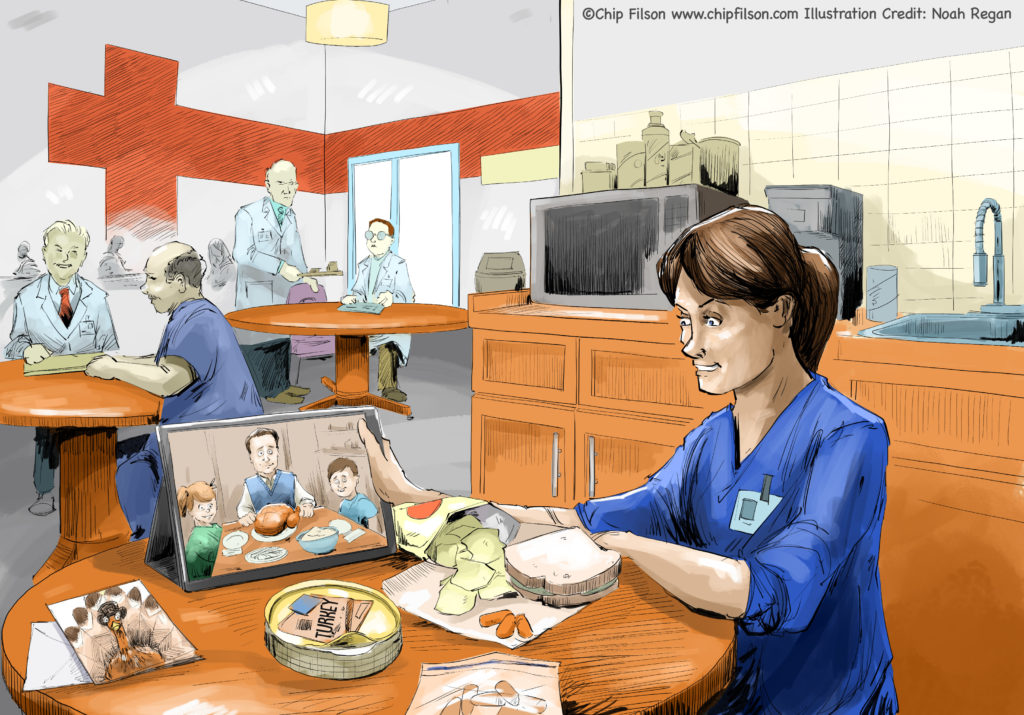

In 1974, Peggy Holliday, CEO of Burbank Schools FCU, started student run branches at two Burbank High Schools. Each campus had a Student Credit Union Treasurer, who would “work” the student credit union during lunch, opening accounts and performing basic deposit/withdrawal transactions.

After school, the Student Treasurer would come to Burbank Schools FCU and reconcile the deposits/withdrawals of the day and process the membership forms to open the accounts.

The experience taught students the real-life skills of money management, budgeting, balancing cash drawers, and basic financial transactions. Students learned the concept of compound interest and making loan payments. Some went on to build careers in the credit union industry.

In 2011, the student credit union branches were disbanded. As account access became available online, the need for in-person transactions diminished. Promoting loan products became challenging, due to regulations. Checking accounts required parental authorization, difficult during school hours. Additionally, as school security increased, hallways became locked down during lunch, and access to the dedicated student credit union room became an issue. Finding student volunteers also became challenging.

But the focus on offering great service to students continued with UMe Credit Union (formerly named Burbank Schools FCU). UMe has an ATM on the quad at Burroughs High School, offers scholarships to Burbank grads, provides a student intern program and offers financial workshops and “Bite of Reality” financial simulation experiences. Additionally, UMe has some student-centric savings products created to help the younger generation get a head start on saving money.

Growing loyal student members by helping teach smart money management is a continued business effort for UMe. They think of themselves more as “helpers” than bankers, which is why they believe in promoting the cooperative spirit to their next generation of members.

From High Schools to Universities

Credit unions, especially those with educational FOMs, continue to sponsor student run credit unions or branches in high schools throughout the country. Students gained financial skills and become part of a new generation of co-op members.

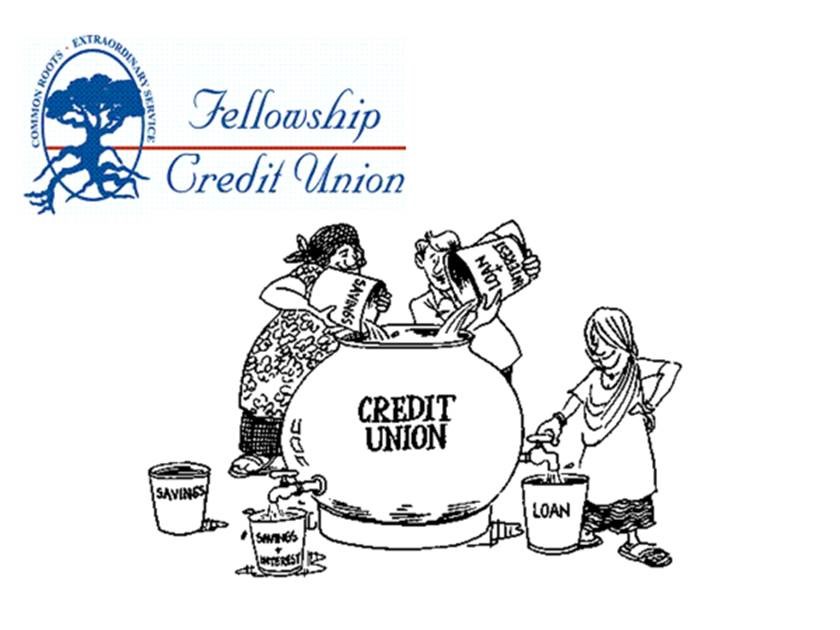

In 1982 to address a falloff in the number of new federal charters (only 114 in 1982), the NCUA launched a renewal program called Credit Union Expansion or CUE-84. The goal was to make credit unions available to many new members ahead of the 50th anniversary of the Federal Credit Union Act in 1984, The committee’s members were a who’s who of credit union CEOs, league and trade association leaders, and state regulators. The one surviving attendee of the 1934 founding of CUNA at Estes Park Colorado, Louise Herring, was on the committee along with Joe Scoggins, CEO of Navy Federal, the country’s largest credit union.

The three-pronged growth effort included chartering new credit unions, expanding FOMs and adding groups such as retirees to credit unions.

The College-University Initiative: Solving a Real National Problem

One important focus was organizing new charters at universities around the country. One example profiled by NCUA was New York University FCU for faculty, all university employees, trustees, alumni and students. Potential membership was 20,000.

The local poster child for this effort was Georgetown University Alumni and Students FCU (GUASFCU) in Washington D.C. Sponsored by the student government, it was open to students and alumni and managed by undergraduates who wanted the experience of running their own co-op.

NCUA changed policy to designate student credit unions as low income, enabling them to accept non-member deposits to fund low cost loans for books and tuition. As explained by NCUA Chairman Callahan:

“This opens the door to alumni through the corporations they work for to make contributions in the form of federally insured deposits which can be earmarked for student loans. Here is a vehicle that could provide a private enterprise approach to something that is a real national problem-the need for student loan funds.”

Of the 107 new charters approved in 1983, NCUA’s Annual Report included a picture of the GUASFCU’s first annual meeting. Also highlighted were charters for the University Student FCU (University of Chicago) and Skidmore Students FCU in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Recently GUASFCU’s Hoya Banking model with $17 million in assets announced a grant from the University to underwrite a secured loan for all incoming students so each could establish a credit score of 685 or greater by graduation.

Current Chartering Environment

From military recruiters, to political parties to businesses seeking the loyalty of new consumers for their products, high school and colleges are target markets for every institution that wants to remain relevant in society. Most major college campuses now have a bank branch on the grounds, or nearby, to serve students.

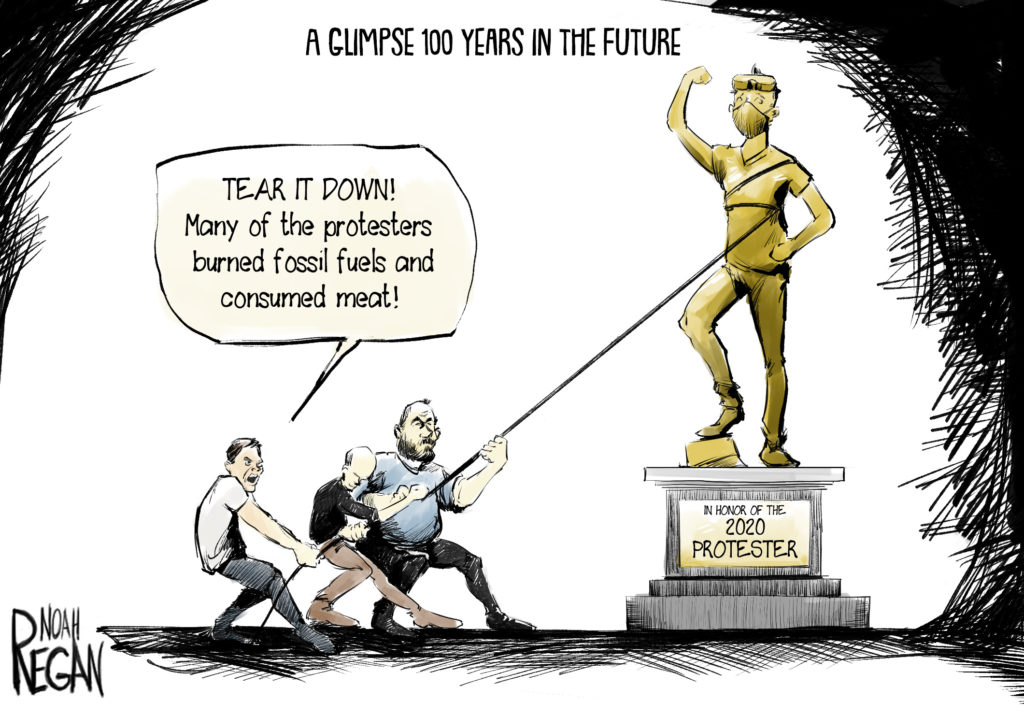

Gen Z and millennials embrace activism, engagement and technology to create new ways of participating in economic and social change. Starting new enterprises is one hallmark of this creative impulse.

Responding to this student interest, over 220 colleges and universities across the country provide innovation and entrepreneurship programs to encourage this activity. (https://www.acceleratorinfo.com/see-all.html)

These academic business accelerators respond to students wanting change, promote the traditional American spirit of innovation and, if successful, provide a financial return to the school. Many academic institutions now sponsor “shark tank” contests to incent new venture ideas offering dollars as well as in-kind support for winners.

One winner in the spring 2018 George Washington University’s new venture competition was a group of freshmen. They proposed a student managed credit union for their university community. They had three primary goals: provide better value services for the students; offer practical management opportunities for volunteer leaders; and create a prototype that could be easily replicated at other colleges around the country.

These students are business, finance, technical and liberal arts majors. They are volunteers in this multi-year effort receiving no pay or course credit. Now in their fourth year of trying to obtain a charter, they may earn their bachelor’s degree before NCUA approves their application.

The Problem for Credit Unions

If students are not part of credit unions’ recruiting efforts, the industry is losing the battle for the next generation of leaders and members. Unlike many areas of civic endeavor or business enterprise, cooperative solutions are best understood when experienced first-hand. They are not a dominant form of organizational design in America’s capitalist economy.

Earlier NCUA efforts, recognized the need to encourage the use and formation of credit unions for all groups. Especially students. Now less so. But the needs of Americans in 2020 and forward are not that much different from 1980.

A Cooperative Opportunity: HBCUs and NCUA

Chairman Hood has announced his ACCESS initiative (https://www.ncua.gov/access) to promote financial inclusion. To put real work, not just talk behind this concept, NCUA should reinvigorate the student credit union charter effort.

For example, there are 107 historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the country. Fifty-six are private and fifty-one public. The democratic Vice-Presidential candidate is a graduate of Howard University whose credit union has charter # 648 (1935) but apparently does not include students.

Can here be a program with local credit union mentors (the Burbank Schools model) to launch credit unions at HBCUs around the country? It would bring a new generation into the cooperative experience as members and managers. Successful examples like GUSAFCU are operating. The benefits are known.

There is nothing more inclusive than the empowering persons through self-help. That is how all credit unions began.

The need is leaders willing to move forward. The ball lies in NCUA’s court. No one wants to wait four years to receive a license to start an enterprise. Especially a cooperative where community progress, not individual enrichment, is the motivation.

If NCUA were to initiate such an effort it would stop working its way out of business and start seeding the economy with a new generation of cooperators. It would also:

- Turn the industry to a new vision for itself.

- Extend the NCUAs role in the expansion and success of cooperative solutions.

- Point credit unions to new heights for mutual benefit, versus consolidation.