In justifying whole bank purchases credit union CEOs will reference learning from their competitor’s experiences and banking knowledge. Several areas include expanded commercial loan opportunities, entry into new markets and adding staff with different expertise.

Trying to beat the competition by becoming the competition has always been a dubious strategy. Moreover, the example of early competition from the Morris Plan banks suggests credit unions will be more successful developing their own unique competencies.

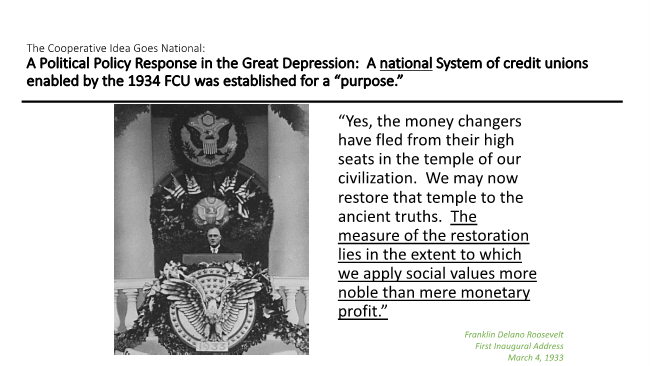

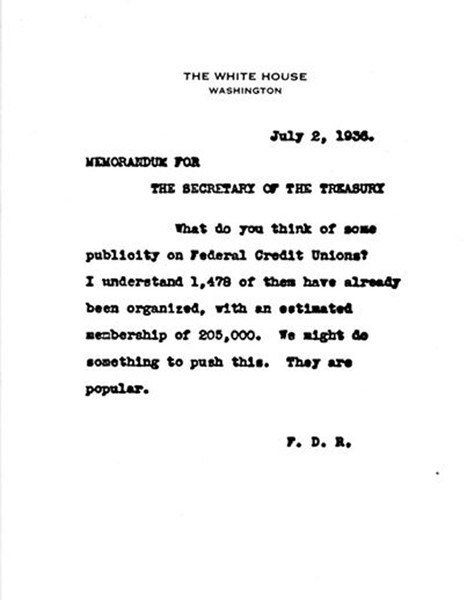

Credit union success was never guaranteed. In fact, one of the earliest and largest competitors for the untapped consumer credit market grew much faster and was far more consequential than the slowly emerging credit union system. That is, until the 1934 passage of the FCU Act ushered in a new era of cu expansion.

Morris Plan Banks

In 1910, attorney Arthur J. Morris (1881–1973) opened the Fidelity Savings and Trust Company in Norfolk, Virginia.

The Virginia lawyer, was troubled that a securely employed workman, seeking a small loan, was denied access to credit from local banks and forced to borrow from loan sharks. Morris thought that a country that denied bank loans to a large part of its population had a “weak spot” in its banking system. Morris studied the various banking laws in the U.S. in the hopes that some type of “banking institution could be evolved that would correct the existing evils and supply credit to the needy”

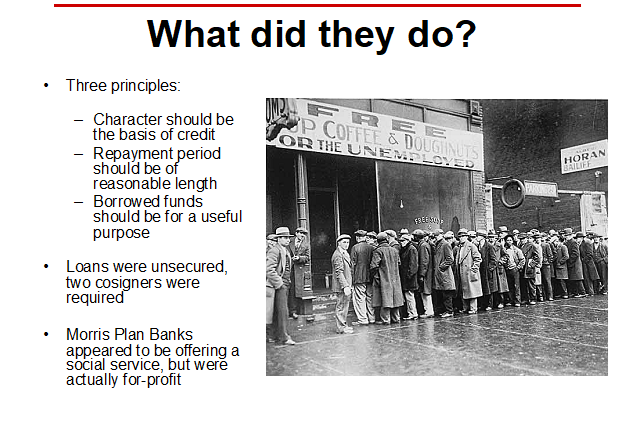

Under a concept called the “Morris Plan” he offered small loans to working people. In this approach would-be borrowers had to submit references from two people of like character and earnings power to prove the borrower’s creditworthiness. Repayment of the loan was made through the weekly purchase of Installment Thrift Certificates equal to the face value of the loan, less origination and investigative fees.

Morris Plan Banks expanded relying on state charters just as did the nascent credit union movement. By 1931, there were 109 Morris Plan banks operating in 142 cities with an annual loan volume about $220,000,000.

In a November 23, 1931, TIME magazine personnel announcement, the industry’s two decades of success and growth were described as follows:

“Walter W. Head, past president of American Bankers Assn., was elected president of Morris Plan Corp. of America, succeeding Austin L. Babcock. Morris Plan Corp. has large stock holdings in all the Morris Plan banks, the largest industrial banking system in the U. S. In the last 21 years these banks loaned $1,750,000,000 to 7,000,000 people, and now do about $200,000,000 annual business with 800,000 customers.”

Morris Plan banks pioneered the use of automotive financing through arrangements between the Morris Plan Company of America, the holding company for Morris Plan banks, and the Studebaker Corporation. In 1917 through the subsidiary Morris Plan Insurance Society, credit life insurance was offered to pay off any outstanding loan balance if the borrower died. Any insurance left over went to the borrower’s estate.

In their description of Morris Plan banks, authors Phillips and Mushinski offer one explanation for model’s success versus credit unions:

“The Morris Plan structure was more attuned to the individuality of typical Americans than were credit unions.

“It should also be noted that the Morris Plan was not without critics, especially from the Russell Sage Foundation which viewed the lending procedure to be misleading at best, and at worst, an attempt to defraud the borrowers. Hence, many viewed the profit-seeking Morris Plan institutions as little better, and in some respects worse, than loan-sharks.”

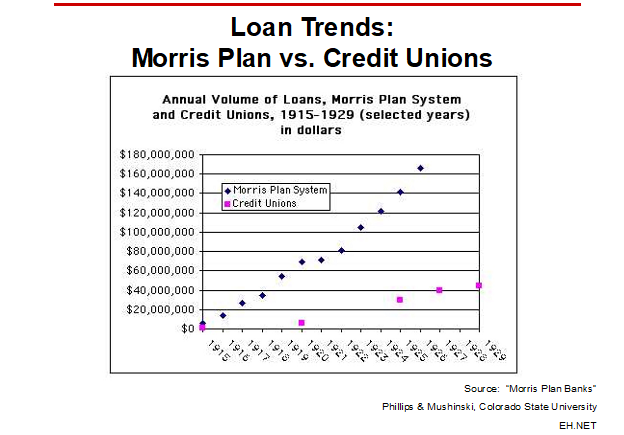

Morris Plan Banks vs Credit Unions’ Growth

Morris Plan banks began the same year as credit unions. In just two decades, by 1931, they became the leading provider of financial options for consumers.

The following slides summarize this state chartered, for-profit enterprise.

1. Begun by a lawyer to meet the need for unsecured personal credit.

2. Innovative legal structure incubated in the state chartering system.

3. Loans were made based on character, for a good purpose with at least two cosigners of similar economic standing.

4. Morris plan banks’ annual loan volume in 1931 is estimated at over $200 million. The state-chartered credit union system reported just over $40 million.

5. Morris Plan banks failed during the Depression. Many converted or were sold to commercial banks which took consumer deposits and had broader lending options.

Today the descendant of this banking model is the Industrial Loan Company (ILC) state chartered, FDIC insured banks that primarily serve as specialty lenders.

Morris Plan institutions relied on wholesale funding and stock subscriptions. Credit unions which offered savings options and consumer loans quickly became the preferred option for members and communities in the Depression. Their non-profit cooperative design, self-help appeal and local leadership created a positive reputation and loyal members following numerous failures in the banking system following Roosevelt’s bank holiday in March 1933.

Some Reflections for Credit Unions from the Morris Plan Experience

- Being first to prove a market need and establishing a dominant position does not guarantee ongoing success. Second movers can create a long-term advantage.

- Growth requires innovation and staying in touch with a market’s needs.

- The more flexible the institutional model, the greater the chance of sustainability;

- The Credit Union system took on a new wave of expansion and credibility when a federal charter option became available—Morris Plan banks were dependent on state-by-state legislation;

- Values and perceptions matter. Although Morris’ instinct was to serve the unbanked, the for-profit structure created a public perception of conflicting purposes.

- Dramatic or sudden changes/crises in the economic, social, or political environment can lead to demise of models developed in another era.

Buying Used Up Models?

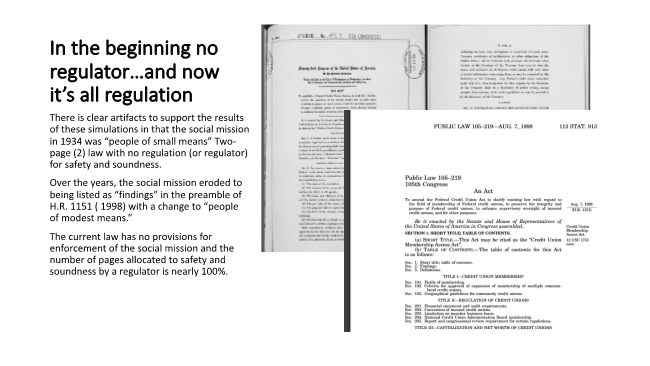

As credit unions pursue whole bank acquisitions, are they buying “tired” business models built with different values and goals? Are these credit unions giving up the advantages of cooperative design and innovation attempting to purchase scale? Will combining competitors’ experiences (and customers) with the credit union tax exemption create an illusion of financial opportunity that fails to prove out when evaluated years down the road?

Two decades ago, the prophets of cooperative doom were selling charter conversions, first to a mutual option and then later, going public with stock. The pitch was: more capital flexibility, no common bond restraints and expanded asset and investment options. And oh, you could also make a lot of money if the former credit union went public.

Between 30-35 credit unions bought into this vision of future financial nirvana. Today only one institution remains, still a mutual whose growth has trailed its cooperative peers since the conversion took place. But that is a story for another day.

We know the fate of the Morris Plan banking model and the “consultants” siren calls to convert to another financial charter. We don’t know if bank purchases will indeed add value for members or their co-op.

But we can learn one thing from history—if these purchases do not create a stronger cooperative, the credit union’s future may have just been attenuated in this effort to induce growth by paying out members’ collective wealth to bank owners.