In Illinois, the initial state credit union act prohibited officers and directors from borrowing from their own credit union. The act authorized chapter credit unions to meet those official’s needs as well as serve members of any groups too small to form their own credit union.

When I became Illinois credit union supervisor in 1977, this restriction had been removed. However the concept that persons managing money should be subject to special scrutiny remained. As one colleague noted, one aspect of our job was to keep honest people honest.

Examiner Norman Glazer

Illinois conducted an annual exam of its 1,000 plus charters. An important part of the onsite visit was reviewing all official family loans, their relatives and the travel and other expenses they charged the credit union.

Examiner Normal Glazer looked like a bookkeeper. He wore wire rimmed glasses, was slight of stature, talked in subdued tones and was a long-time state employee. He was a very thorough examiner, who knew accounting and more importantly, the many ways that humans might conceal wrongdoing.

I asked him how he reviewed the loan and savings verifications looking for fictitious accounts. It was simple-he selected a sample of each, and then looked up the names in the phone book. If there was no name, he dug further.

Among Norman’s discoveries was a $1.0 million embezzlement from the Scott Foresman Credit Union where the manager kept a double set of books and accounting ledger cards. When Norman’s tape of the individual ledger cards did not match the GL total, he sensed something was wrong. He refused to accept the “missing cards” explanation and found a completely separate set of ledgers with which he documented the full amount of the loss. CUMIS paid the claim he substantiated.

Human Nature Has Not Changed

I cite this Illinois examination practice in support of Board member McWatters and others who have publicly observed that fraud is the most common cause of NCUSIF’s losses.

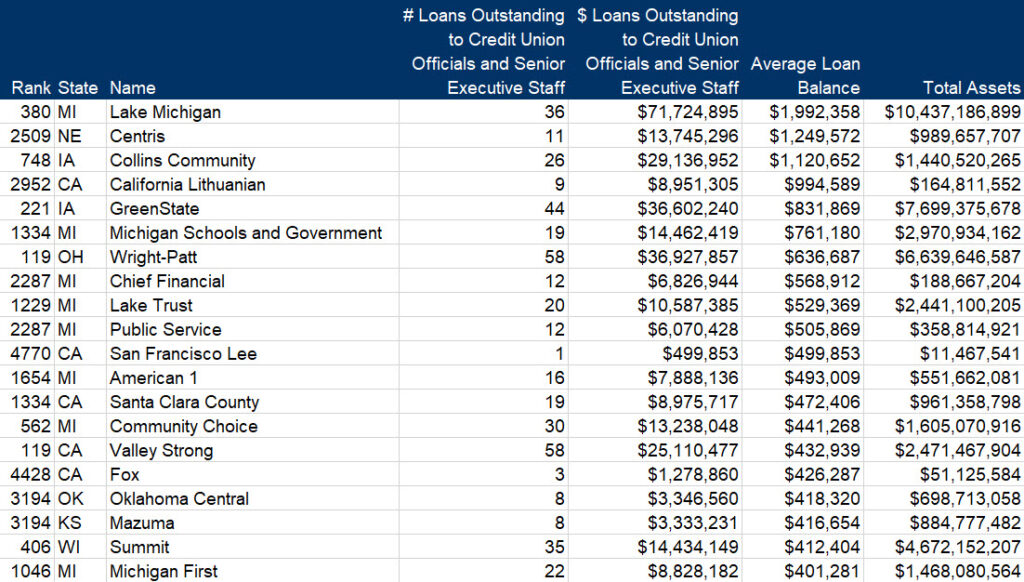

The historical concern about senior managers and directors engaging in self-dealing has a 5300 call report “echo.” Account codes 995 and 996 show the number of loans and total dollar amount to this leadership group. The table below lists the top 20 credit unions by highest average loan balance with total loan numbers and balances as one way of reviewing the data.

This table shows wide variations in this activity even among these 20. The list by itself might prompt some obvious questions; however, the point is NCUA still believes this is an activity for ongoing monitoring—or is it?

Job # 1

NCUA’s largest budgeted amounts and the majority of its workforce are dedicated to on-site exams. One assumes all loans, family related transactions and the expenditures charged by senior staff and directors to the credit union would be reviewed as normal exam protocol.

Reporter Peter Strozniak of the Credit Union Times regularly follows NCUA’s legal filings and court documents. From these records he describes the details of these internal thefts and other employee/director wrongdoing, unfortunately years after the credit unions’ failure. These detailed accounts show that examiners have overlooked extended periods of self-dealing.

A recent example is from the Time’s report of NCUA’s suing CUMIS for recoveries from Melrose Credit Union’s CEO. His October 15, 2021 story described one NCUA claim:

Prior to his 1998 retirement, Herb Kaufman, Kaufman’s father, was Melrose CEO and served as the board’s treasurer. In May of that year, Herb Kaufman became an independent consultant to Melrose under the terms of what the NCUA described as an unusual three-page agreement, which was signed by only one member of the board who turned out to be a life-long and close friend of Herb Kaufman.

The agreement contained a one-year renewable term that paid Herb Kaufman $5,600 a month for his services.

“Despite his obvious conflict of interest, Kaufman aggregated solely to himself the over site within the Melrose Consulting Agreement with his father,” the NCUA lawsuit reads. “Thereafter for more than 18 years, Kaufman covertly caused the renewal of his father’s Consulting Agreement without ever informing the Melrose board or otherwise bringing its continued existence to the attention of the Board.”

According to the NCUA, Herb Kaufman was paid $1,239,795 over 18 years and failed to generate any business for Melrose or provide any meaningful consulting services to the credit union. What’s more, Melrose also paid Herb Kaufman’s travel expenses of more than $26,000 even though his consulting agreement stipulated the travel expenses were to be paid by Herb Kaufman.

The facts offered by NCUA say the Melrose President paid his father (the retired CEO) for 18 years without a fully approved contract.

Assuming an annual NCUA and state exam, this arrangement went un-noted for almost two decades. How could this be? Same last name, monthly checks, a written agreement-it raises the question of what do examiners look at? And NCUA is asking CUMIS to pay up because the bond company should have detected this?

This is not the first time NCUA has sued CUMIS for credit union failures.

On April 23, 2010 NCUA placed the East Lake, Ohio-based St. Paul Croatian FCU in conservatorship with an estimated loss of $170 million, or almost the entire amount of insured shares balance. Loan fraud was among the primary reason for the CU’s collapse.

The IG significant loss report stated:

At St. Paul Croatian FCU, examiners didn’t assess the weakness of the credit union’s internal controls and failed to ensure that the credit union took corrective action on document of resolution issues.

How does NCUA atone for its exam failures? The CU Times report: The NCUA filed a proof of loss claim with CUMIS for nearly $72.5 million (St Paul Croatian FCU). However, because CUMIS’ fidelity bond has a $5 million coverage limit, the amount of money in dispute would be less than 7% of that figure, said Phil Tschudy, a CUNA Mutual Group spokesman.

Between this 2010 St. Paul failure and the October 2021 CUMIS suit for Melrose recovery, there have been repeated cases of significant examination failures over multiple exam cycles. Three of these are described in this post. The information, all from court proceedings, documents CEO embezzlements lasting years. In the CBS Employees FCU case, the CEO fraud extended for two decades resulting in an estimated $40 million loss to the members.

NCUA’s Two-foldProblem

These recurring, costly examples, suggest that NCUA is not doing well its number one job of examination. Examiners should be given a whole new process and trained on reviewing self-dealing activity.

But it is hard for NCUA to fix a problem that is hidden from public scrutiny until years after the fact.

A second challenge is NCUA’s lack of transparency. It provides no information on its supervisory actions. The agency has said nothing about its current conservatorships, one of which is over $4billion in assets. But then years later court proceedings show how extensive and elongated the pattern of misconduct and coincident examination shortcomings were.

Generalized IG critiques of exam failures provide no details of the examiner oversights or any mention of accountability. The response to IG findings is by the same people responsible for the entire process in the first place.

Accomplishing Job # 1

With all the recent public remarks by NCUA leadership about cyber ransomware, cryptocurrency, DEI, climate change and other current “risk” topics, the agency seems unable to perform its most important, historically necessary, oversight function effectively.

Examinations produce pages of financial statements, ratios and trends, and checked boxes for policy adequacy. Almost 97% of credit union assets are held by Code 1 and 2 rated credit unions. The biggest risks are internal, not on the balance sheet.

Examiners should be training for conversations about all forms of self-dealing to see who approved what, when and why. These discussions should be part of the exam record. The topics should be raised and documented in the board exit conference. Without putting these activities in the light of day during exams, everyone presumes it’s OK to keep questionable activities in the dark, and out of the record.

Where is Norman Glazer when credit unions need his sixth sense, or rather common sense? For example he might look at the table above and ponder why are real estate loans to senior credit union personnel so much larger in the lower priced Midwestern states than in any of the more expensive big city coastal markets?

I know he would have challenged a $35 million dollar sinecure committed to a newly organized non-profit by two merging credit unions to support the “advocacy” activities of the CEO who arranged the merger.

The fiduciary concepts of care and loyalty would appear to have been erased from NCUA’s examination and supervision process a long time ago.

Credit union members pay the costs of these failures. However in the long run its is the public reputation of NCUA and the system that is at risk when examinations miss the obvious.