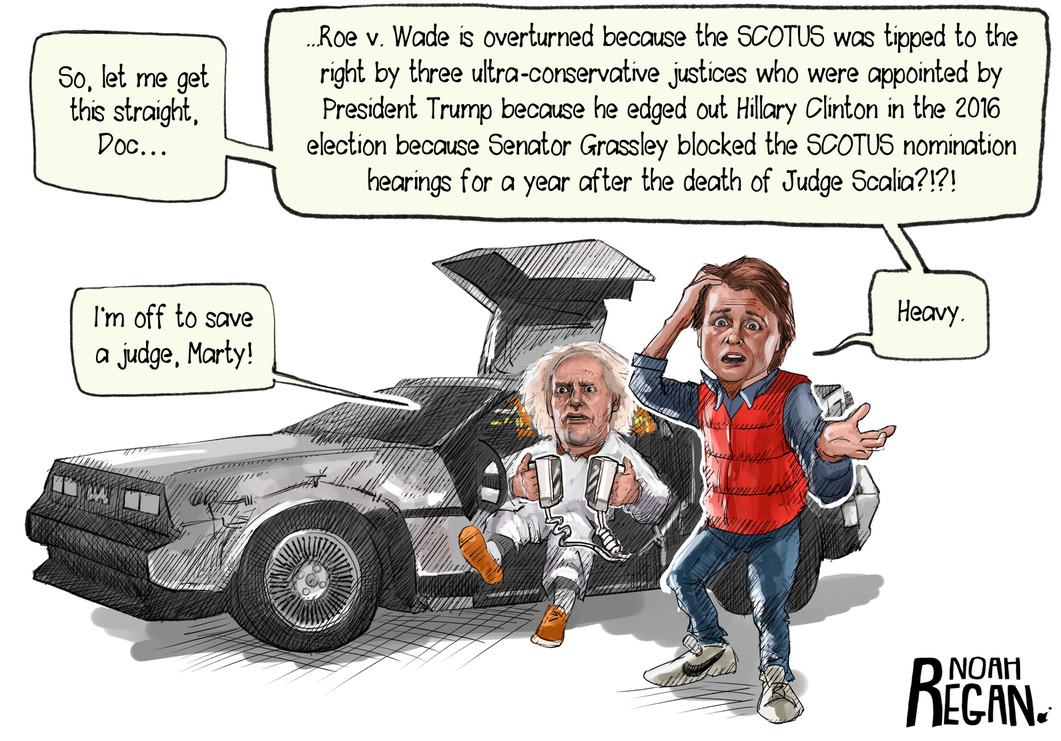

Back to the Future

Noah Regan’s cartoon below portrays the logic of the Supreme Court’s overturning the Roe v. Wade precedent.

Supporters of the decision openly assert this puts the US back to what the situation was 50 years ago. The “freedom to choose” right will now be a state by state determination. The legal circumstances will vary widely in every jurisdiction. Even within a single state, the decision could be modified anytime there is new political leadership elected.

Women and their partners will find themselves in an ever changing legal and/or criminal status. This was an overt political decision. The courts and lawyers demonstrated their profession’s singular ability to present arguments about woman’s rights that are completely contradictory to each other. Therefore the solution will be political, not legal.

A Credit Union Perspective

How does a Supreme Court decision that goes against both precedent and common sense get changed?

Two of the current justices were involved in the NCUA vs. First National Bank and Trust case decided in February 1998 in a 5-4 decision written by Justice Clarence Thomas. The lawyer presenting the NCUA-credit union position was John Roberts, now Chief Justice of the Court.

The court ruled that the NCUA’s interpretation of § 109 of the Federal Credit Union Act (FCUA) that: “federal credit union membership shall be limited to groups having a common bond of occupation or association, or to groups within a well-defined neighborhood, community, or rural district” -permitted federal credit unions to be composed of multiple, unrelated employer groups, each having its own distinct common bond of occupation” was incorrect.

NCUA General Counsel Bucky Sebastian in 1983 had interpreted, and the Board agreed, that in section 109 the word “groups” was plural, and therefore authorized multiple group charters.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Bank position that the NCUA’s decision was contrary to law because § 109 unambiguously requires that the same common bond of occupation unite each member of an occupationally defined federal credit union.

Justice Thomas wrote: “the NCUA’s interpretation makes the statutory phrase “common bond” surplusage when applied to a federal credit union made up of multiple unrelated employer groups, because each such “group” already has its own “common bond,” employment with a particular employer. If the phrase “common bond” is to be given any meaning when the employees in such groups are joined together, a different “common bond”-one extending to each and every employee considered together-must be found to unite them.”

This Supreme Court also overruled a district court’s decision that NCUA had correctly interpreted § 109 following the Chevron precedent of deferring to Agency discretion when implementing a Congressional statute. Note: this week the Supreme Court is expected to announce a decision which may modify the Chevron precedent.

The Credit Union Response

This FOM ruling would have put federal credit unions back into the legal and practical world of 1934 when the Federal Act was passed. The court decision ignored the entire history of credit unions and the evolution of financial services under deregulation. Common sense and real world events made the court’s finding both impractical and a potential end to the federal chartering option.

For decades almost all state systems had much more flexible common bond regulations than NCUA’s. If the ruling stood, there would have been a wholesale conversion to state charters.

Credit unions mounted a coordinated and united campaign to change the federal law to continue NCUA’s common bond interpretation that had been followed for almost 20 years. The result was the passage of the Credit Union Membership Access Act (HR 1151) by congress and signed by President Clinton on August 7, 1998. This action preserved the NCUA’s FOM regulations albeit with a new set of regulatory requirements under the label of Prompt Corrective Action.

In this situation the state system was where consumer’s freedom to select a coop financial option was preserved.

Women’s Rights

In the Roe decision, the return to the states to determine what rights a women has, will have the opposite effect of the credit union example.

The Court’s decision echoes an earlier time in our history: “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” Lincoln warned Americans. “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided.”

The credit union case is very different in scope and political significance. However both decisions show the Court’s willingness to turn back the clock, to ignore real world consequences, and throw issues back to the political process.

The common thread in these retro interpretations is the role of Justice Thomas. He wrote the credit union opinion and assigned the Roe one.

The Roe reversal will, as in the credit union circumstance, require political action. The court’s abortion decision resolves nothing. Like the credit union case, it will eventually come back to congress.