Hans Christian Andersen’s story about the emperor who had no clothes is familiar to most. You can read the parable here to refresh your memory. Two swindling weavers convinced the entire court and the emperor that their invisible new uniforms were perfect. They pocketed the gold and silver threads for the garments stealing them for their own use.

I have always wondered why it took a small boy in the crowd watching the king’s parade of “new” clothes to shout out, “But he hasn’t got anything on.” What was the reason for everyone else’s silence?

- Fear of authority when challenging the emperor’s actions?

- Loss of a senior position if a trusted advisor should speak up?

- Who am I to argue with the emperor’s wisest, most senior advisors?

- Onlookers: not my problem if the emperor wants to go out naked

- Too isolating to be a person stating an inconvenient truth?

- Situation so far-fetched that no one believes the facts before their eyes?

- Perhaps an example of: “you can fool all the people some of the time”

Whatever the explanation, the story raises the issue of people avoiding uncomfortable realities that no one else wants to acknowledge. In the merger situation below, a single thoughtful and brave member decided to call out what no one else would, even though the facts were presented in plain sight.

The Merger of Financial Center and Valley Strong Credit Unions

On May 31, 2021, Michael Duffy, CEO of the $643 million, 65-year old Financial Center Credit Union(FCCU) announced the intent to merge with the $ 2.4 billion Valley Strong:

The phrase ‘Growing Together,’ is a perfect adage, as this merger represents a strategic partnership between two financially healthy, future focused credit unions committed to providing unparalleled branch access, digital access, and amazing service for the Members and the communities they serve,” says Michael P. Duffy, president/CEO of Financial Center. “In a financial services sector that is constantly evolving, this merger is a true embodiment of the credit union industry’s cooperative mind-set. At its core our partnership with Valley Strong represents us selecting the best credit union partner to help us achieve our goals faster than we could duplicate on our own.

“As the CEO of Financial Center Credit Union for the past 21 years, my perspective on mergers has evolved just as much as our industry has in that same time period,” Duffy continued. “As credit unions built by select employee groups (SEGs) increasingly partner with community credit unions, I have marveled at what credit unions of today’s scale can accomplish when they join forces with their Member-owners and communities chiefly in mind.”

The 86% member approval in the merger vote was announced in a September 27 Valley Strong press release which included this statement by CEO Duffy explaining the rationale:

“In a financial services sector that is constantly evolving, this merger is a true embodiment of the credit union industry’s cooperative mindset. At its core, this is about a collective mindset that allows us to achieve our goals faster than we could duplicate on our own.”

When asked what it means to Members to achieve these goals faster, Duffy added, “We recognize merger critics may point to our healthy capital and ask why we didn’t just opt to go it alone. That was of course the first consideration. But the reality is, we do the same things for the same reasons so why not eliminate redundancy and grow faster and better together. On our own, it would take years to develop and implement while still having the challenges scale, so why not give members more and build the organization for the next decade at the same time.” Duffy continued, “We took our national search for a partner seriously. Together with Valley Strong, it’s a win-win, because members are the focus, and we will be able to serve even more people throughout San Joaquin and the state of California.”

The Member-Owners’ Notice of the Merger

As required by NCUA rule, FCCU provided members the reasons for the merger. These general descriptions included “consolidation of energy and resources, to better serve members through competitive pricing and services, additional products, enhanced convenience and account access and continued employee and volunteer representation.”

The member Notice then listed seven categories of benefit with a little more detail. For example, Duffy will become Chief Advocacy Officer for Valley Strong and be “actively involved in the day-to-day operations.” In addition, the Notice described two contributions to a non-profit charitable foundation FCCU2. More on this community outreach initiative later.

Share Adjustments and Golden Handshakes

At midyear 2021, FCCU had net worth of 16% totaling $107 million or twice the ratio of Valley Strong. The Notice included a special dividend distribution of almost $15 million based on two factors.

- Each member will receive $100 for every five years of membership to be capped at $1,000 for members who joined in the oldest tier 1946-1976.

- A dividend of .869% on the 12-month average balance for “Base” shares with a $500,000 ceiling on the maximum shares included.

Each member’s pro rata share of the net worth at the merger vote is $3,620. However, the credit union will pay only an average of $505 per member just 14% of their common wealth. To equalize FCCU’s with Valley Strong’s per member net worth, each member should have received an average of $1,800.

The four golden handshakes, that is additional compensation over and above what employees would have earned without the merger, will be paid to:

- Nora Stroh EVP for $150,000 if she stays with the new credit union for 30 days following the merger;

- Steve Leiga, VP Finance of $150,000 for staying 30 days after merger completion;

- Amanda Verstl, VP HR $257,352 for retention, severance opportunity, accrued sick and leave payout;

- David Rainwater VP Information for $244,000 for staying through the system conversion.

These special payments are similar to other merger transactions although the special dividend structure is unusual and recognizes the generations of member loyalty.

Two questions arise from these disclosures in the Notice:

- Why would a $643 million credit union with over 16% net worth and $521 million in investments believe it is unable to provide competitive member services and pricing into the future?

- And why did CEO Duffy not receive any merger payment? The Notice further notes that he and the VP finance would not receive anything from the one-time bonus dividend.

Some Context

Michael Duffy joined the credit union in October 1993 and has been President for over two decades. The EVP and COO, Norah Stroh, has been with the credit union for almost 32 years. She joined as HR, benefits and personnel manager in February of 1990. In January 2001, she was promoted to her current number two role.

Michael and Norah are brother and sister.

Steve Leiga, VP Finance, joined the credit union in January 2002. Amanda Verstl’s employment at FCCU exceeds 13 years. David Rainwater’s connection began as a summer intern in 2011.

For an experienced team to suddenly decide merger is the best course for members after three decades seems somewhat unusual no matter the rationale. Why are the senior leaders of this credit taking their severance bonuses and closing up shop? Where is the succession planning, or was merger a predetermined strategy?

One FCCU trend seems especially puzzling. Why is there no Lending VP? Who had this responsibility for this most critical role in every credit union? The loan to asset ratio has declined in the last five years from 39% to 16.9% at June 2021. The $107 million in reserves equals the net amount in outstanding loans, for a risk based net worth ratio of 100%. All the $521 million investments are in cash or government and GSE securities.

When reviewing the two last available 990 IRS filings for the credit union, a dramatic change occurs.

In 2017, the three most senior employees were paid a total of $1.4 million or 21% of total salaries and benefits. In 2018 the three were paid $3.1 million, or 46.5% of total salaries. The 121% increase is in just one year. In both years the CEO is a member of the five-person board which approved these compensation packages.

No IRS 990’s are yet available for 2019 and 2020 to know if this trend continues. It would certainly be useful for the credit union to post public copies of these required filings in light of the merger decision.

A Million Dollar Public Contribution-Conflating Personal and Professional Roles

As the credit union’s lending portfolio continued to decline and member numbers fell from a peak of 32,382 in 2017 to 29,101 today, the credit union made a very public contribution to the city of Stockton.

In April, 2020 Michael Duffy presented a $1.0 million check to a COVID relief effort, the 209 Stockton Strong fund. The subsequent press release described the effort as follows: “This donation represents a continued commitment from the entire FCCU team. They are donating, together, out of the care and concern for others in their local community. . . Duffy presented this opportunity to the FCCU team as a way to help their community and received immediate support with a resounding yes.”

Even though the announcement states the $1 million donation is from “the entire FCCU” team and the Michael Duffy Family Fund, there is no information of how much came from each source. The only public reference to the Duffy Family Fund is as one of several donor advised funds managed by the Community Foundation of San Joaquin.

The mayor’s office prepared for Facebook an 11 minute video of this donation featuring Duffy and a six foot enlarged check with the credit union’s name. And here is this brief excerpt on the KRCA evening news.

Philanthropy can certainly be positive. Donor advised funds are an easy way for individuals to manage the timing of their contributions. But it can also be self-interested. This $1.0 million single “gift” is one of the highest donations I can recall associated with a credit union during this time of COVID, or any other time.

The credit union or Duffy could certainly have donated the money to the identified charities directly. Why Duffy would combine his personal philanthropy with whatever the employees donated for this appeal is unclear.

One might suggest this conflation of professional and personal activity is a PR effort to promote the credit union, not just Duffy.

However, the IRS 990’s show credit union funds given to a wide number of political campaigns. There were 17 donations totaling $60,250 in 2018, including a second $10,000 contribution to the current CA governor, and donations to Stockton’s mayor. Is this credit union money to political campaigns in the members’ best interests, or to promote the public influence of Duffy?

Why the Merger? Why did the CEO do this?

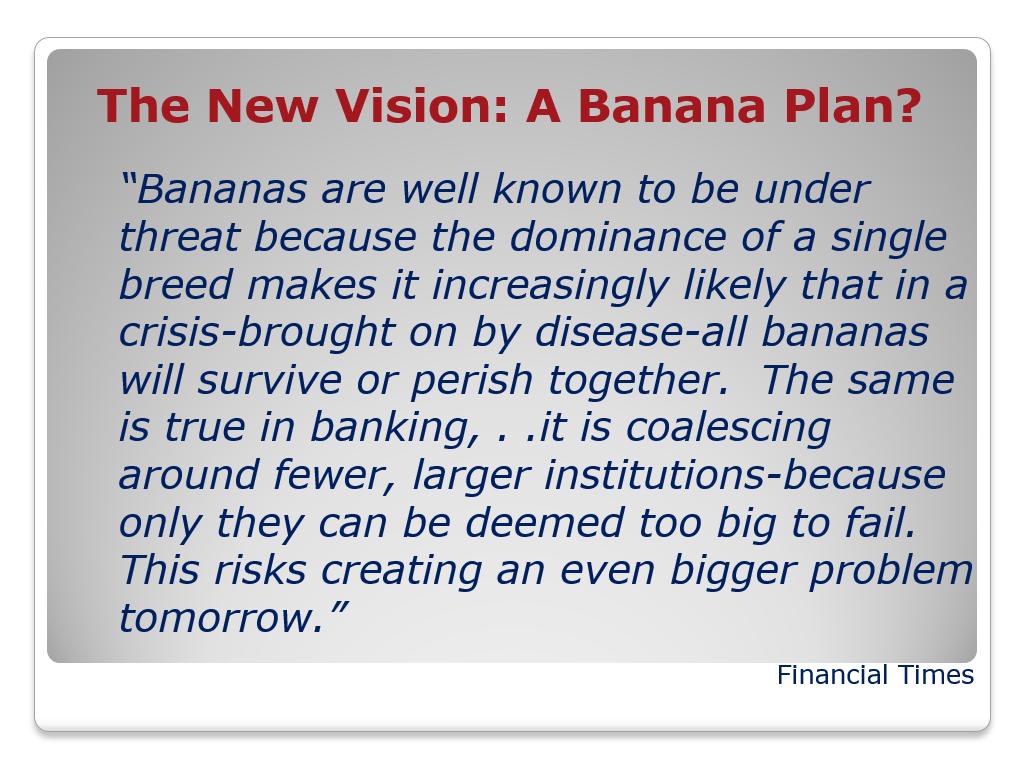

FCCU has been a closely-run, family operation for almost three decades. The CEO is a member of the five-person board. The credit union is more than financially sound, with its very liquid balance sheet and net worth two and a half times the well capitalized 7% standard and twice Valley Strong’s ratio of 8.7%.

Why would the entire leadership of the credit union give up their 66-year history of relationships at the peak of financial capability? Motivations can be hard to discern. But on August 26, 2021, a member posted his analysis for opposing the merger on NCUA’s website for comments:

Vote NO on the proposed merger until the provision to transfer $10 million of member assets to a non-profit foundation for “Community Outreach” is eliminated from the proposal. Member financial assets of any amount, especially $10 million, should not be given away for any purpose. If Financial Center Credit Union is so flush with cash that it wants to give away $10 million, then that amount should be distributed to members. I’ve written to FCCU twice asking for the rationale for giving away $10 million. They have failed to answer me, obviously because there is no rational reason for giving away $10 million from its member-owners.

Given that FCCU’s current CEO Patrick Duffy is being given the unexplained job of “Chief Advocacy Officer” in the Continuing Credit Union, it’s easy to guess that Duffy’s only job duties will be running the new foundation doling out the $10 million to his favorite groups and his own large compensation. The so-called “FCCU 2 Foundation” was created less than two months ago for setting up Duffy in his new give-away-our-assets role. In any case, FCCU’s failure to explain to members any rationale for GIVING AWAY $10 MILLION OF MEMBER ASSETS is insulting and outrageous. Vote NO on the merger until the $10 million giveaway of our assets is eliminated from the merger proposal.

The FCCU2 Foundation was set up on June 25, 2021. The two persons listed with the registration are Manuel Lopez, the credit union’s chair, as the Foundation’s CEO; Michael Duffy is the agent for service. The organization is described only as a domestic non-profit. Its address is the same as the credit union’s main office in Stockton. As stated in one other public notice: The company has one principal on record: The principal is Michael P Duffy from Stockton CA.

The member merger Notice states the total funding committed for this new foundation is $35 million. There is the initial grant of $10 million from the members’ reserves at FCCU. The Valley Strong members are committed to donate $2.5 million per year of their funds for the next ten years for the remaining $25 million.

The purpose of the non-profit in the merger Notice is: “community outreach-charitable and educational activities to benefit the greater Stockton area.” No further rationale is provided why this entirely new organization created and run by Duffy should be given $35 million of members’ money.

A lone member, Frederick Butterworth who in August posted on NCUA’s comments page makes the obvious point: this emperor has no clothes.

The Duty of Care and the Duty of Loyalty

But the situation is more serious than the action of establishing a $35 million fund as a personal sinecure for CEO Duffy as he transfers leadership of the credit union to another board.

In a widely publicized court sentencing hearing last week of a former credit union CEO the following statements were made in court:

U.S. Attorney Audrey Strauss: The (CEO) shirked his duty to act in the best interests of the credit union and its account holders, exploiting his position for personal gain.

Federal prosecutors said the CEO viewed the credit union as his personal fiefdom, repeatedly betraying his fiduciary duties to the institution and its members.

“This was a family-run business,” Judge Kaplan said of the credit union. . . “If you ran a delicatessen you could do what you want. But this was a federally insured credit union and you were oblivious to that fact.”

The fiduciary duty of directors and managers is more than avoiding criminal conduct. NCUA’s legal suits against selected corporate directors and management were based on violations of their fiduciary duties of Care and of Loyalty.

Were the boards and managers following these standards when committing $35 million of member money to the FCCU2 Foundation to fund the work of the Chief Advocacy Officer Duffy? Is this two-month-old foundation just a means of providing future compensation to the former CEO? Was this ten-year funding commitment from Valley Strong a requirement of the merger?

Whatever word one uses to describe this setup -a bonus, a buy-out, or a quid pro quo/kickback-it appears to be a betrayal of fiduciary duty to the members of both credit union by their respective CEO’s and directors.

In March NCUA conserved the $ 106 million Edinburg Teachers Credit Union with a 22% net worth ratio and a loan to share of 14.6%. The only public information suggested by the media for the action, given the strong financials, was the average compensation of $189,000 per employee and the CEO’s compensation in excess of $8.7 million over the past eleven years. The Texas Commissioner explained the conservatorship as “to ensure the businesses in these industries. . .are entitled to the public’s confidence.”

All NCUA participants from the field examiner to the highest levels in DC admired the clothes this emperor said he was wearing. NCUA’s RD and assistant RD, the supervisory examiner, CURE which posted the Notice and member comment, and the California Department of Financial Institutions, liked what they saw.

All were bystanders to this event without asking why a 66-year-old credit union, overly-liquid and over-capitalized with a declining loan portfolio and inbred leadership could not continue to be run as an independent credit union for the benefit of its member-owners. But perhaps that has not been the case for years. The CEO just took the logical next step.

The Hans Christian Andersen parable above ends as follows:

“Did you ever hear such innocent prattle?” said its father. And one person whispered to another what the child had said, “He hasn’t anything on. A child says he hasn’t anything on.”

“But he hasn’t got anything on!” the whole town cried out at last.

The Emperor shivered, for he suspected they were right. But he thought, “This procession has got to go on.” So he walked more proudly than ever, as his noblemen held high the train that wasn’t there at all.

Is NCUA playing the emperor in this modern version and just walking on by? Are other credit unions the crowd? Might the “whole town” be today’s public press and Congress?

One vigilant and thoughtful credit union member proclaimed the truth about this situation. He gave a shout out to everyone. Is anyone listening? Or do we continue to live in a fantasy land complying with regulations that don’t protect the members who credit unions were designed to serve?