A reader sent the following after reading Ed Callahan’s last interview as Chairman of NCUA. In that conversation he focused on the relationships between the agency and credit unions.

Hey Chip – I am just reading this. My husband and I were camping in the wilds of Utah with very sketchy service. In the “old days” it truly was a partnership with the Agency.

Being a CEO my entire career, I was always highly engaged with the Examiners when they were in my credit union. It was always a very positive relationship where we learned from each other. Unfortunately, it devolved over the years into an “I GOTCHA” encounter. . .

Losing Our Heart and Soul

Greetings Chip! I continue to read your blog . . . After the latest news about more Illinois credit unions merging, I finally felt compelled to write down my thoughts on this issue.

I will publish his thoughts in the future. These are his opening paragraphs:

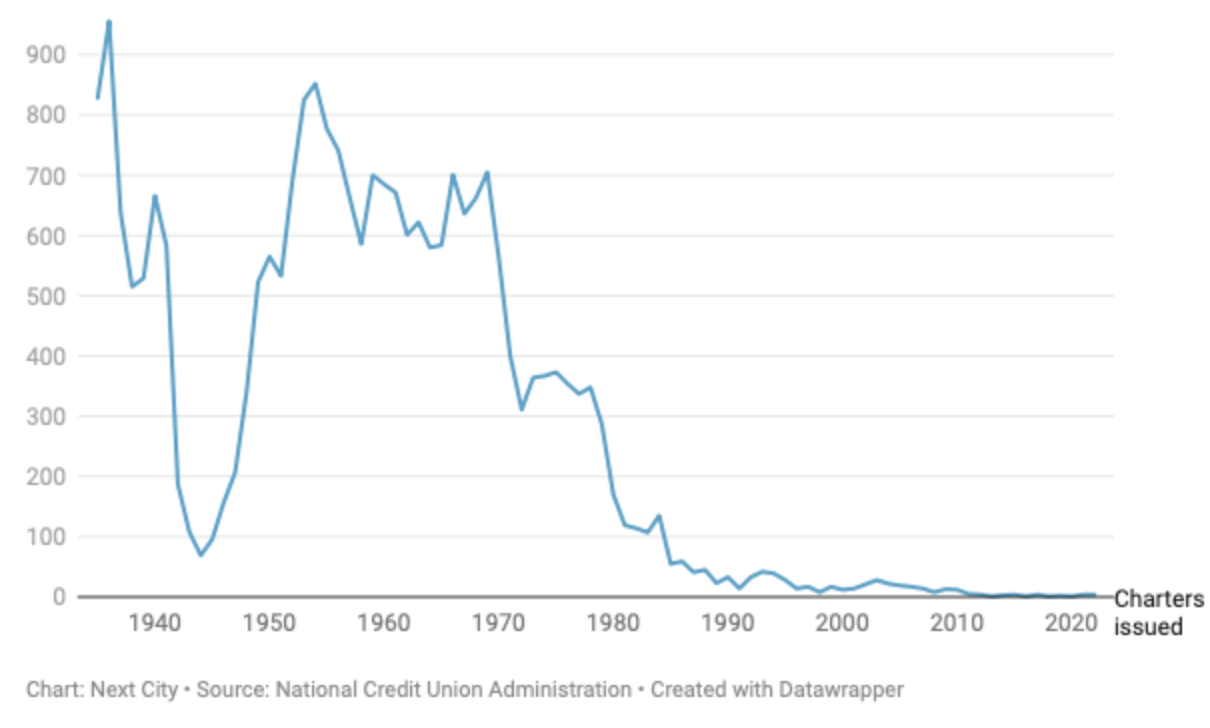

Credit union mergers have been happening for decades. Some are forced by the regulators, some are voluntary, and there are a multitude of legitimate reasons. But as I celebrate 32 years in this industry, it is still sad to see the number of credit unions that disappear every single year, and to see the pace of mergers pick up every year. When we lose our small credit unions, we are losing the heart and soul of our movement that makes credit unions special.

I know that no matter the size, credit unions are still member-owned, not-for-profit financial institutions. But it is difficult to argue with the fact that as we grow larger, whether organically or through mergers, that members have less of a voice. . . And I fear that we are becoming just another industry, instead of a movement.

No Longer a Movement?

There is no doubt credit unions are becoming more and more “mainstream.” They tout their promotions with professional sports franchises, stadium naming rights and multiple business partnerships.

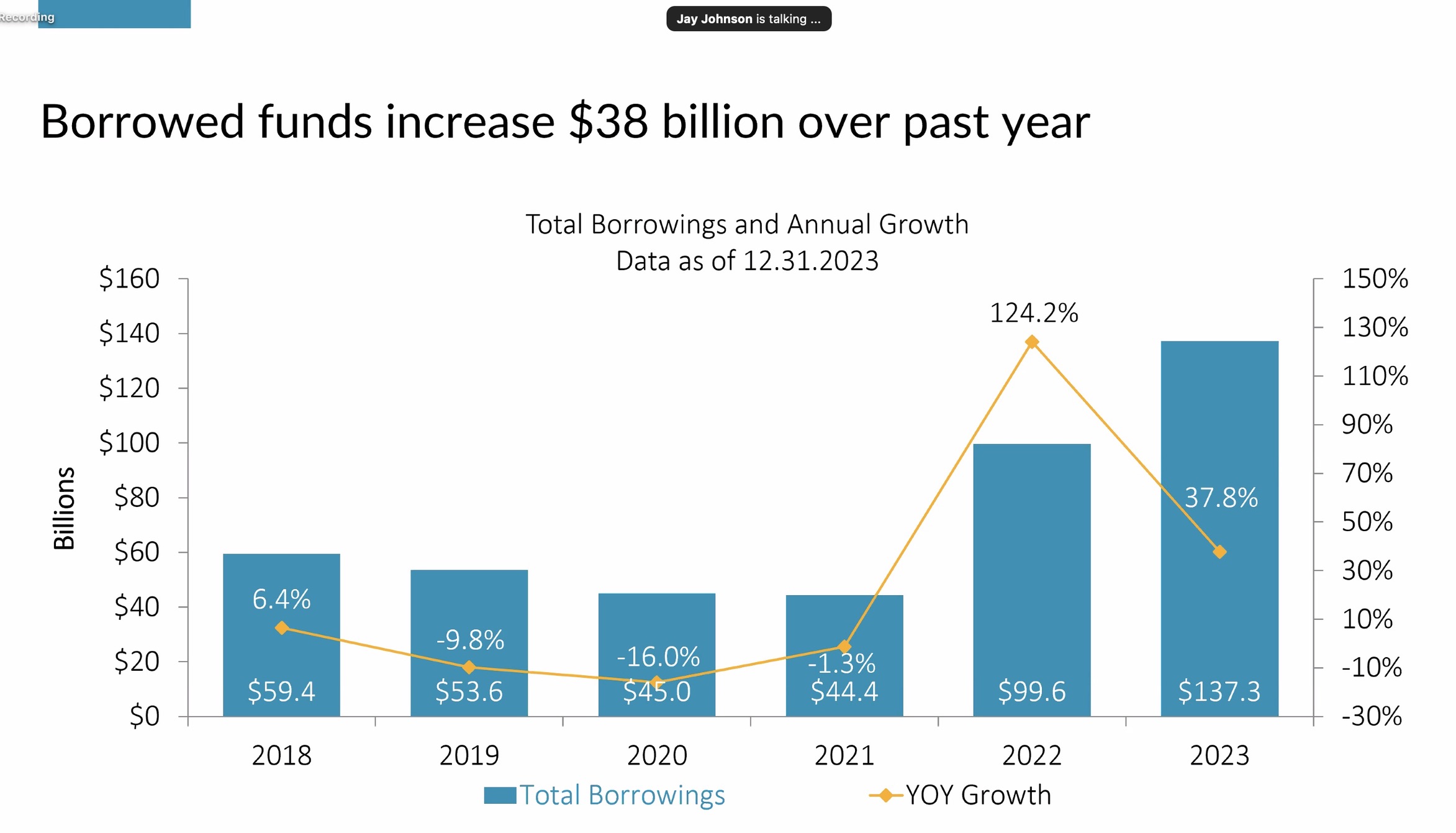

Growth is the dominant success indicator. Credit union lobbyists argue in tandem with banks against the consumer protection initiatives of the CFP. NCUA’s Chair cites the FDIC as a financial model for the NCUSIF and positions his supervisory initiatives because that is how banking regulators act.

In becoming an important component in America’s financial sector, have credit unions also embraced the status quo? Are they more concerned with protecting their achievements than addressing the economic inequities members face in the economy?

An observer might give examples on both sides of the “movement” issue. However, I believe credit unions are not alone in their constant temptation to be seen as fully engaged participants in the so-called “free market.”

“The Only Game in Town”

Franciscan scholar Richard Rohr describes the ever-present allure of America’s economic system this way:

Most of us have grown up with a capitalist worldview which makes a virtue and goal out of accumulation, consumption, and collecting. It has taught us to assume, quite falsely, that more is better.

It’s hard for us to recognize this unsustainable and unhappy trap because it’s the only game in town. When parents perform multiple duties all day and into the night, that’s the story line their children surely absorb. “I produce therefore I am” and “I consume therefore I am” might be today’s answers to Descartes’ “I think therefore I am.” . . .

The course we are on assures us of a predictable future of strained individualism, environmental destruction, severe competition as resources dwindle for a growing population, and perpetual war. Our culture ingrains in us the belief that there isn’t enough to go around, which determines most of our politics and spending. . .

F. Schumacher said years ago, “Small is beautiful,” and many other wise people have come to know that less stuff invariably leaves room for more soul. In fact, possessions and soul seem to operate in inverse proportion to one another. Only through simplicity can we find deep contentment instead of perpetually striving and living unsatisfied. . .

St. Francis knew that climbing ladders to nowhere would never make us happy nor create peace and justice on this earth. Too many have to stay at the bottom of the ladder so some can be at the top. . .