An S&P 500 company was projected to last for more than 60 years in the last half of the 20th century. Today that lifespan is down to 18 or fewer years.

Many believe this shortening of business’ existence is merely the accelerated playing out of economist Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction, i.e. the free market at work.

However there is another way of looking at business sustainability by asking which are the oldest business still operating today. What can their stories tell us versus the inexorable extinction that seems to be the market’s dominate outcome?

Several articles trace the origins of these Methuselah-like firms that have existed for centuries. Their commonality is that they provide products or services that people always need: wine making or breweries, inns and hotels, weaponry/foundries and mints, and personal services such as Shore Porters or an Istanbul Turkish bath.

The Oldest Federal Credit Unions

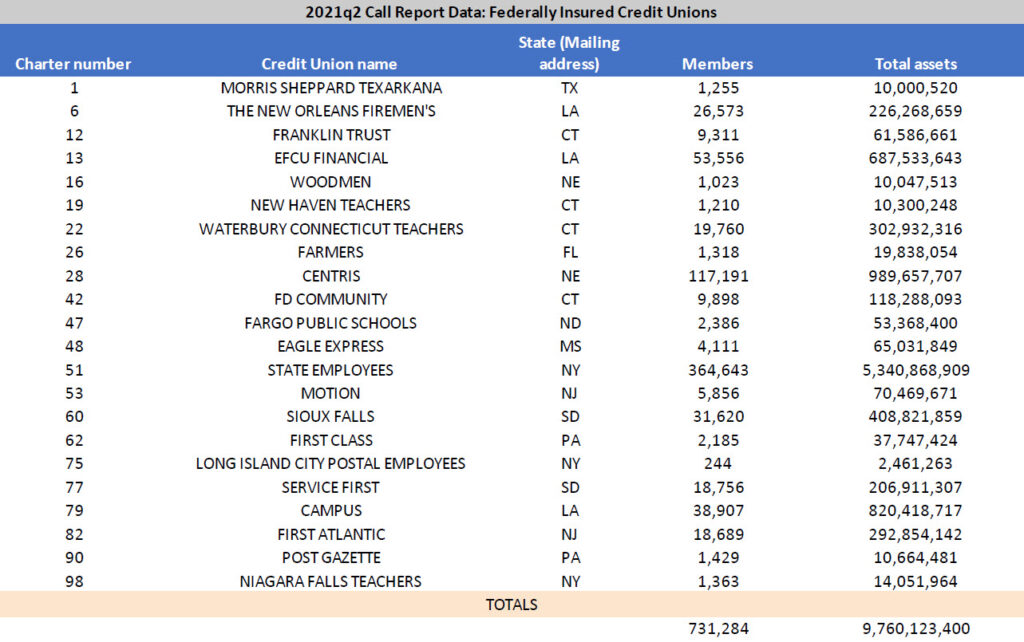

NCUA’s June spread sheet of all 5,032 federally insured credit unions gives everyone the chance to analyze FCU charters by longevity. The latest financial performance information is laid out in charter number order. Starting with charter #1 Morris Shepard Texarkana to # 24,927 Credit Union of New Jersey, a conversion from a state charter founded in 1943.

While some FCU’s conversions from states are much older than their indicated by their fed charter order, the vast majority listed through the early 1980’s are an accurate indication of institutional longevity.

While most credit union adherents know the first charter was from a state, St Mary’s Bank in 1909, the evolution of the federal charter is less documented.

Of the initial 100 charters granted by NCUA, 22 are still active. These are listed below.

These initial charters were granted in 1934/5 during the Great Depression, immediately following passage of the 1934 Federal Credit Union Act. These startups have persevered through nine decades of economic cycles, WWII, financial deregulation, competitive reconfigurations, and technology changes unimaginable by their founders.

Their survival rate, 22%, is almost double that of all FCU’s which is 12.6% (3,146 active charters and 24,927 issued). What can we learn from these long- serving charters? How can their stories provide insight for today’s credit unions? Is there a reason they have twice the sustainability as FCU’s generally?

Initial Observations on Sustainability

I am not familiar with any of these credit unions, however reviewing the data here are some initial thoughts along with questions that might be interesting to pursue.

The 22 are diverse in size, number of members and geographic location. From $2.4 million to $5.3 billion in assets, they demonstrate the diversity and flexibility of the coop charter. It serves all institutional sizes, towns and cities and geographic regions.

Of the eleven states where these credit unions operate, four are in Connecticut. Why? Was there not a state charter option, and therefore the initial credit unions were all federal?

Many of these initial charters served persons working in the public sector: firemen, postal workers, teachers, state employees and a university. Even Morris Shepard, charter #1, initially served the city employees of Texarkana. These public sector sponsors still exist and in many cases have expanded.

Is the relative stability of their public employment a key to credit union sustainability? For example, Long Island Postal Employees reports only 244 members and $2.5 million in assets. But it is still supported by these members with an office in the basement of the Post Office.

Credit Union History Still Present For Us

Understanding credit union history is about more than honoring longevity. Their experiences can be instructive for present day prognosticators.

Cooperative design is intended to be perpetual. Privately owned firms rarely transition beyond their initial founders. Public companies including banks can be bought and sold in the open market at any time.

Coop capital is paid forward to benefit future members. While every credit union is subject to the forces of a competitive market, outright failures are rare.

However there are a number of seers who routinely offer their view that coop design is not sufficient for longevity. In their foretelling what is required is size (scale), the latest technology and “innovative” strategies which emulate their competitors.

While several of these long-timers might validate these tactics, most do not. Rather the common factor that seems to sustain is what created the credit union in the first place: the service to and loyalty from the members. Morris Shepard FCU’s origin statement on their website says it clearly:

As a member-owned, not-for-profit financial cooperative, Morris Sheppard Texarkana FCU will continue to uphold its fundamental responsibility to actively serve people within our field of membership, which consists of the employees of the City of Texarkana TX, City of Texarkana AR, Bowie County and their spouse, children, and grandchildren. We will continue to deliver a range of low cost products and services to the diverse economic and social makeup of our members and potential members.

They continue to celebrate their first in the country creation:

Our History

Morris Sheppard Texarkana Federal Credit Union was named in honor of U.S. Senator Morris Sheppard, who represented Texas in the Senate from 1913 to 1941 and was one of the credit union movement’s greatest supporters in Congress. Senator Sheppard drafted several pieces of credit union legislation in the early 1930’s. But it wasn’t until 1934 that the passage of a Federal Credit Union bill appeared likely, thanks to the efforts of Sen. Sheppard and another Texan who had become convinced of the bill’s importance, Congressman Wright Patman. Our local credit union chapter, an affiliation of credit unions, is named after Congressman Patman.

What These 22 FCU’s Help Us See More Clearly

I’m not sure what is in the cooperative DNA of these credit union managers and boards. But it might be worth learning more about. For if their attitude and efforts had been shared by the entire FCU system, the could be as many as 2,338 more credit unions active today. They would not necessarily be a State Employee or a Long Island City Postal, but they would be serving a perpetual need human need with an institution they own.

Today credit unions rarely close due to external forces or financial failure. Rather leaders of sound institutions at the close of their tenure merge their credit union to reward themselves with an additional cash payment. Unfortunately, credit unions are not exempt from personal cupidity.

One of the lessons these 22 and the oldest commercial companies provide: the needs for these services does not go away. That alone should be enough to keep the lights on when the harbingers of combinations issue their predictions of inevitable consolidation.

And the enduring need for values based, honorable leadership of these organizations.