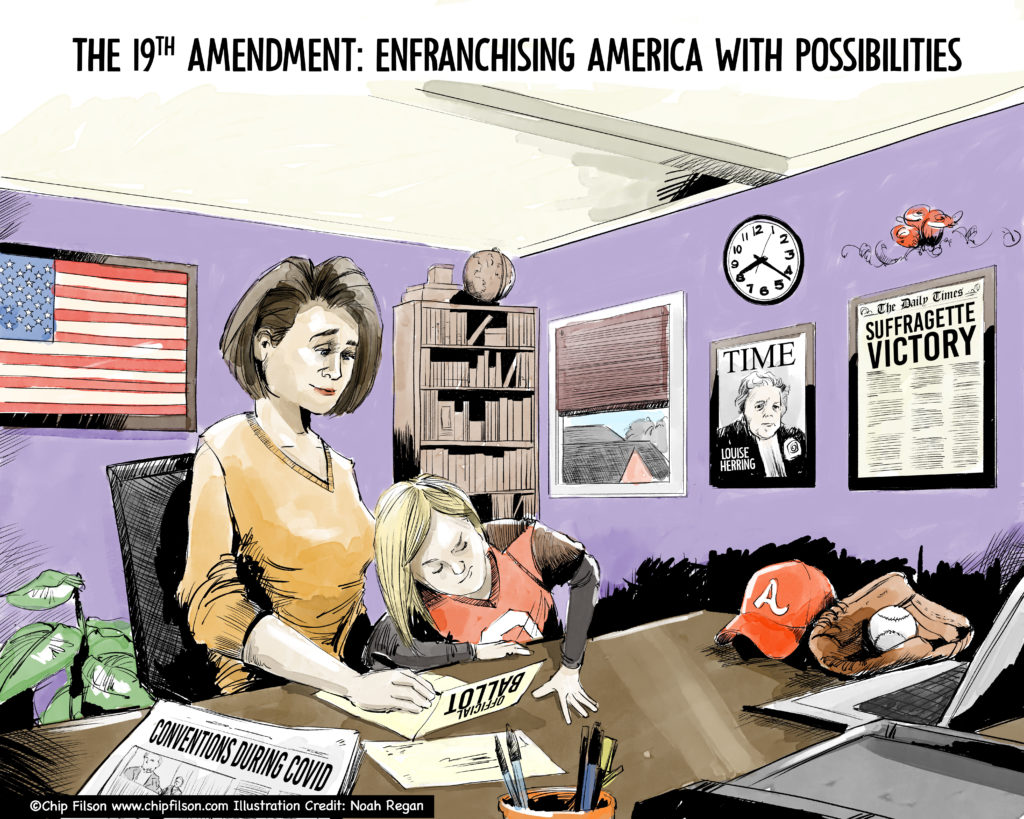

The legacy of credit union pioneer Louise Herring (1909-1987) is vital to the creation of the modern day credit union movement. As summarized in her alma mater’s profile, she managed Kroger’s first credit union and founded a dozen more while helping to charter over 500 credit unions in her five decades of activity. To support these nascent charters, she formed local chapters, the Ohio League and the private insurance alternative known today as ASI.

Most importantly she was the youngest woman to attend the Estes Park Conference in 1934 which founded the Credit Union National Association.

More Than the Sum of Her Accomplishments

Through the force of her personality, she shared her passion for credit unions in all circumstances. The following is a story from the book Sharing the American Dream, published by the Credit Union Executive Society.

It is a small but typical example of how the 19th amendment created possibilities for women’s leadership benefiting all Americans far into the future.

Neither snow nor jail could stop Herring

by Louise McCarren Herring

This excerpt comes from the book “Sharing the American Dream,” from the Credit Union Executives Society.

I almost always organized credit unions at a change of a shift or before or after working hours. One night, I went to a meeting of teachers in Columbus, Ohio. The meeting ended about 9 p.m., and since I had scheduled a meeting with the Dayton, Ohio, police for early the next morning when the late shift went off and the first shift came on, I decided to drive the 70 miles to Dayton that night. Even though it was snowing and most people would have said in those days that it was foolish to drive at night, I started out.

I got to the outskirts of Columbus and saw a streetcar parked at what I thought was the end of the line. I passed the streetcar and was immediately stopped by the police for passing a streetcar that was loading and unloading.

An officer took me back to headquarters downtown where I was told I either had to pay a fine, post bond or go to jail. Because of the snowy night, many officers were sitting around either coming off duty or waiting to go on. They listened as I explained that I could do none of these things because I had to be in Dayton early the next morning to organize a credit union for the police force there.

As I explained what a credit union was and the good it could do for working people, the officers sitting around started to pitch money up on the table to pay my fine. I made each person who contributed to my fine give me his name and address so I could repay him. Finally enough money came in to pay the fine and I was dismissed, with a date to return to organize a credit union for them.

They thought the idea was so good they were willing to pay to have a credit union organized. It gave me the opportunity to tell them, as I have told so many groups, that no one should pay to get a credit union.

(Roy) Bergengren and (his colleague Edward) Filene had secured the laws and organized the credit unions as a public service. Those who received this service without cost or obligation had a responsibility to see to it that anybody who wanted a credit union should get it just as they did — without cost or obligation.

Bergengren often paid lawyers and other local people to organize credit unions. He never paid me because I felt it was a great privilege to organize credit unions in the hours I was not working on a full-time job.

The first credit union I organized was for the members of the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks. I knew nothing about organizing credit unions so I spent the entire meeting reading aloud the bylaws and explaining the brief but exciting history of the credit union movement. Later on, I was able to cut down the time it took to organize a credit union.