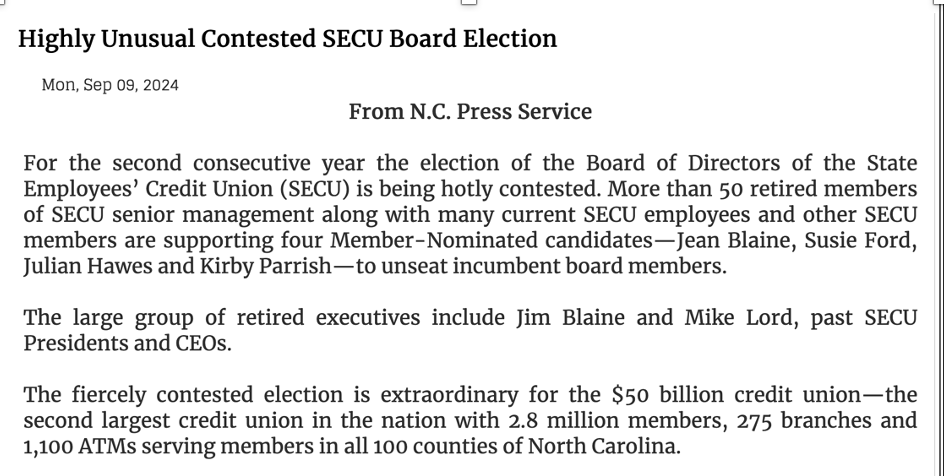

The largest member vote in a credit union board election resulted in the slate of four incumbents all winning by a wide margin.

The cumulative total vote for the four winners was 232,452 (67%). The four member-nominated candidates total was 113,117 (33%). The headline in Jim Blaine’s blog after the vote was announced: Pretty Strong Thumping!

The outcome was the exact opposite of the 2023 vote where the three challengers to the board slate were all elected. The vote was significant in other respects. Adding the highest total votes for the leaders of each slate, suggests almost (62,392 and 31,203) 94,000 or more members voted.

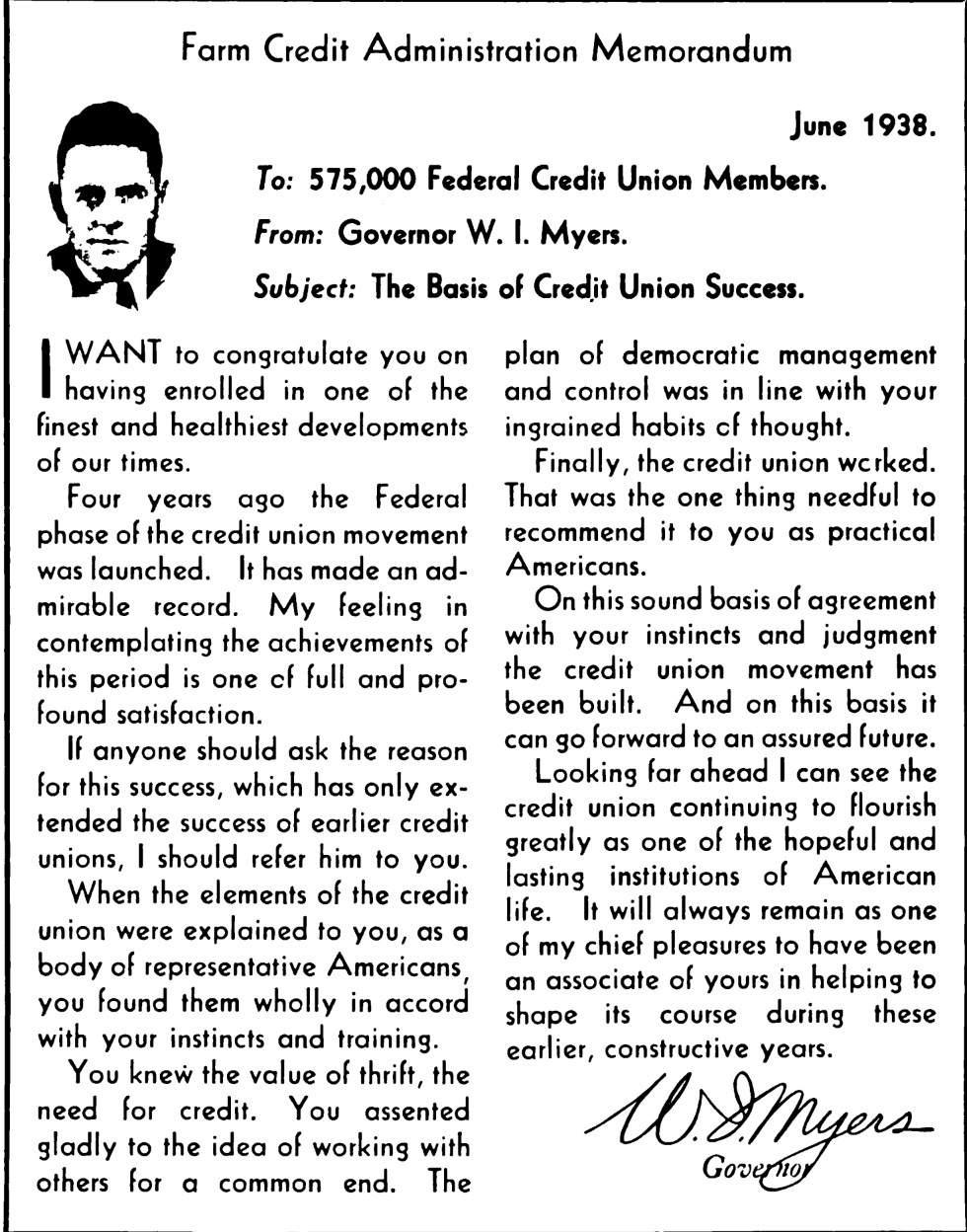

This is an extraordinary level of participation. It shows the interest and willingness of members to participated in the selection of their leaders. Once awakened in their role, will they continue to follow credit union events as more than a customer? Have their ownership “genes” been activated? Will next year’s election involve a choice?

The Substance of the Annual Meeting

The meeting was broadcast on YouTube. SECU staff had posted the results later with the full recording. Also posted are the financial summary for fiscal 2024 and links to the 54 page 2024 CPA audit.

While the vote was the main outcome, that announcement took just several minutes at the very end. The meeting’s substance were reports read by the Board chair, the Foundation’s chair (with video summary) and nominating committee chair.

The most important parts of the agenda were CEO Leigh Brady’s report and then her response to dozens of member questions sent in advance. Putting these two parts together a relevant title for the meeting’s substance might be the Leigh Brady Show.

The CEO’s Performance Report After Her First Year

After opening remarks on Helene’s devastation in Western Carolina and saying all employees were safe, Brady stated her personal vision as, “we work together to leave SECU better than we found it.” (1:03). She provided a summary of major financial trends, both positive and not, showed a chart of an increase in SECU’s share of member loans (25.8%), and compared its loan charge-offs for the first six months of 2024 to the five largest credit unions. SECU’s outcome (.74%) was between Navy FCU’s 2.54% and BECU’s .59%

She introduced a new SECU’s data point, its initial Net Promoter Score (63), as an indication of member loyalty. Her closing was a listing of FY ’25 priorities including new member reward or cash back credit cards, a new mortgage servicing platform, voice authentication, selection of a new core data processing vendor, replacing branch ATM’s and a new digital platform. She noted that several of these initiatives, especially the new core, will extend over multiple years.

Her presentation was well organized, detailed with graphs and comparisons, and with specific priorities for the new year. Her very full report could be a model for other CEO’s in disclosing their prior year’s results and future plans to the member-owners.

Members’ Q&A

The second part of Brady’s role was spending an hour answering 50-60 questions from members that were submitted prior to the meeting.. There were few “softballs” in these queries. And while she may not have fully responded on some points, the questions were the most interesting part of this event for me, and probably the members who submitted them. Here is a small sample of some of the topics raised:

- Why aren’t members able to speak at the annual meeting?

- Will you post all these questions (and replies) on the web?

- Why were members (running for the board) not able to gather signatures at the branches?

- Why are all the board members from one region of the state?

- Tiered base loan pricing had multiple questions such as: Is one member’s financial well-being more important than another’s?

- Does tiered-base pricing exclude anyone? Can lending officers make exceptions to the process?

- Why are savings and money market rates not competitive with other credit unions?

- In the next five years what do you see as the greatest threats to the credit union?

- Does the Board and President feel they are making decisions in the best interests of the members?

- Please explain how the credit union lost $23 million in the CashApp member fraud.

- All board nominations were for persons already on the board. Would setting term limits help with the perception that this (process) is a conflict of interest?

- What is the status of the Local Government FCU’s separation and will it have an impact on the members?

- \What do I have to do to become a member of the board?

- Will the credit union offer digital currency?

- What are SECU’s plans for the secondary (home loan) market? etc, etc, . . Go to the video to learn her responses.

Brady (and Board) in Control

There are dozens more questions, all of which CEO Brady answered. She replied even in areas concerning board conduct and policy or in the case of the CashApp fraud loss, an internal issue.

This hour long Q&A was the most extended explanation, an in-depth discussion I have seen in no other credit union’s annual meeting. Even as it appeared most of the answers were being read from a script, she addressed each topic. Some might feel she failed to see some of the underlying concerns; but no one could argue that all the pointed, potentially embarrassing or even opposing views were not included. She stood her ground.

That stance is the final takeaway. The meeting was a very controlled event. The camera never wavered from only showing the individual speaker. Even when Brady was answering questions, the person asking them was heard but never appeared on camera.

Several times Brady acknowledged attendee’s responses to her remarks, but there was never an audience view. Board members spoke on camera, but were never shown sitting together. The Foundation video and presenter’s slides were seamlessly woven side by side on the screen with the speaker.

This YouTube broadcast was a very well-produced and visually managed event showing only the four speakers and nothing else. No chance for any spontaneity or audience reaction.

Brady closed her CEO presentation by referencing this year’s meeting to include “another contested election” that will not impede our going forward. One cannot help but come away with the feeling that this year’s event was a reaction to the two prior meetings where the board must have felt things moved out of their control. This time the outcome which had some excellent content, especially the member questions, was an exercise in the power of incumbency.

Will that exercise in authority work to promote the members’ and SECU’s long term viability? Or, will SECU just transform into another example of a large credit union similar in operations to its peers?

The Core Issue: Effective Strategy

My understanding of the last two plus years of public controversy about SECU is that the core issue is effective strategy. While there were specific tactical topics such as risk-based lending, critics’ deep concern was whether SECU’s members would be as valued if the credit union offerings just looked like every other financial institution’s.

Aligning SECU’s products and services to conform with the majority ot its peers may certainly garner some low hanging fruit. SECU’s response to critiques of its tiered lending was its intent to “serve all its eligible members,” especially the A credit score borrowers going elsewhere.

The previous cooperative vision of “send us your moma” was centered on members who may not have had A options readily available, and needed a fair and trusted institution to turn to.

Over time this member-centric focus extended to innovations in salary advance loans, broker dealer options, life insurance, a state-wide 529 insured college savings account and even how repossessed real estate was managed. The SECU Foundation’s innovative funding model has made it a marketing presence for the credit union throughout North Carolina.

These financial service expansions were based on a belief that to beat the competition, one cannot simply emulate them. Hence when asked about offering 30-year fixed rate real estate loans conforming to Fannie/Freddie requirements, the response was, Why compete with the government’s product?

Time will tell how this most recent strategic overlay will mesh with the legacy elements on which the credit union was built: its branch structure, decentralized decisions, advisory board roles and unique partnerships within the industry.

The datapoint from the meeting that may be most relevant in this ongoing transformation is the 33% who voted against the incumbents. That number suggests a more studied understanding to integrate past success and current changes might be useful.