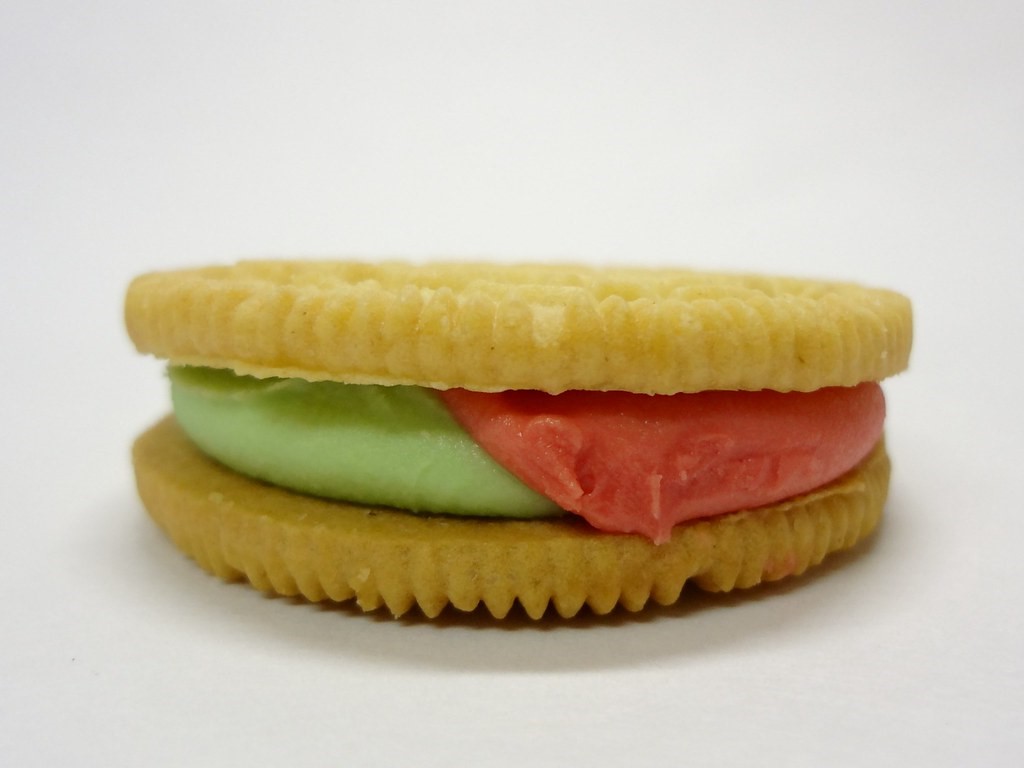

In June 2013, Nabisco’s Oreo, the best-selling cookie brand in the world, introduced a “refreshing” new product extension.

The new Oreo had a watermelon flavor filling to create an association with its summer market launch. The internal flavor coloring aligned well with its Golden Oreo product. Children were a prime target because of their willingness to try new flavors.

One does not have to be a market research guru or have a sweet tooth addiction to suspect this might not be a great consumer success.

On Twitter, responses ranged from, “These sound heavenly,” to “i looked up ‘abomination against nature’ in the dictionary and there was a picture of watermelon oreos.”

One media outlet asked its Facebook followers for comment and received a deluge containing one word, “Eww.”

An econlife review opined: If you really want that “fun, summer flavor,” stick with the real thing and dive into an organic watermelon. They’re limited edition summer treats too, with much healthier benefits.

Harbingers of Failure

Marketers study failures, not just success stories.

In a 2015 paper, marketing scholars from MIT, Northwestern, and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology looked at consumer demand for new products. After gathering data on 8,809 new supermarket products, 439,546 transactions, and 77,744 customers, they concluded that success didn’t necessarily equate to sales growth. The explanation was that consumers who liked the items most were not representative of the total market.

Analysis identified these buyers as exhibiting what marketers labelled “Flop Affinity.” These are people who buy something that really doesn’t resonate with the majority of the market, such as Crystal Pepsi or Lemonade Doritos. These individuals are also more likely to buy a type of toothpaste or laundry detergent that fails in the broader the market.

Traditionally, companies want increased demand. But demand is about more than the quantities; it involves knowing who likes your product. If sales increase because “harbingers of failure” purchase something that most would avoid, then a firm can have a flop on its hands.

But just as important, an NBC story on the study found these group preference choices work the other way around. The data found those “who tend to purchase a successful product like a Swiffer mop are more likely to buy other ultimately successful products, like Arizona Iced Tea.”

The Watermelon Oreos Phenomena in other Contexts

Researchers are exploring how widely this “harbingers of failure” pattern applies in other areas, from everyday shopping selections to financial markets.

Is the concept applicable to behaviors other than choosing consumer products? Do credit union leaders tend to join with others around similar performance patterns?

Can the Watermelon Oreo research also identify behaviors or mindsets that exist within organizations; that is, micro-cultures that can compromise or promote purpose and performance?

Responding to External Demands for Change

In addition to ongoing market competition, every institution today is confronting external pressures for change. These range from the operational pivots responding to Covid to the social and political demands for accelerating equity and economic inclusion.

Northwestern’s Kellogg School identified a range of leadership responses ranging from the least to most meaningful when an organization reacts to external demands. Least effective were public statements of support. The most consequential was finding champions for the cause within the organization and tasking these internal believers in the change to develop the organization’s response.

The Watermelon Oreos case suggests that people’s choices, even if popular in the moment, are not indicative of long-term success. Winners tend to align with other winners in their behaviors whether within an organization or in the distribution of consumer preferences.

Effective leaders put those who believe in the required change in charge and not let the doubters harm their brand or organization’s reputation.