As pundits, regulators and congress have looked at what should be changed in the wake of the three recent large bank failures, one focus is how FDIC insurance is structured.

A precipitating event was mass withdrawals by uninsured customers, prompted by social media alarms. Using their Dodd-Frank “systemic risk authority,” the FDIC took over the banks and covered all depositor balances while it worked to find a least cost resolution.

This customer behavior has prompted suggestions for changing FDIC coverages to reduce this risk potential. CUNA and NCUA have publicly stated that the NCUSIF should have “parity” in any changes to FDIC insurance.

Here is one trade’s position: Credit unions must receive parity with banks in any deposit reform legislation, CUNA wrote to House Financial Services and Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee leadership Monday. Congress and the Federal Reserve have indicated interest in deposit insurance reform in the wake of recent high-profile bank collapses.

“Our primary concern regarding any deposit insurance reform legislation passed by Congress is to ensure that credit unions receive parity, fair treatment, and equal protection with banks,” stated CUNA President Jim Nussle in his letter to Congress.

I believe this public posturing is dangerous to the future of the NCUSIF and to credit unions separate financial system. Here is why.

- Credit union CEO’s and industry leaders have rushed to assure their members, the public and Congress that credit unions do not have the problems that caused the banking failures. They are more financially resilient.

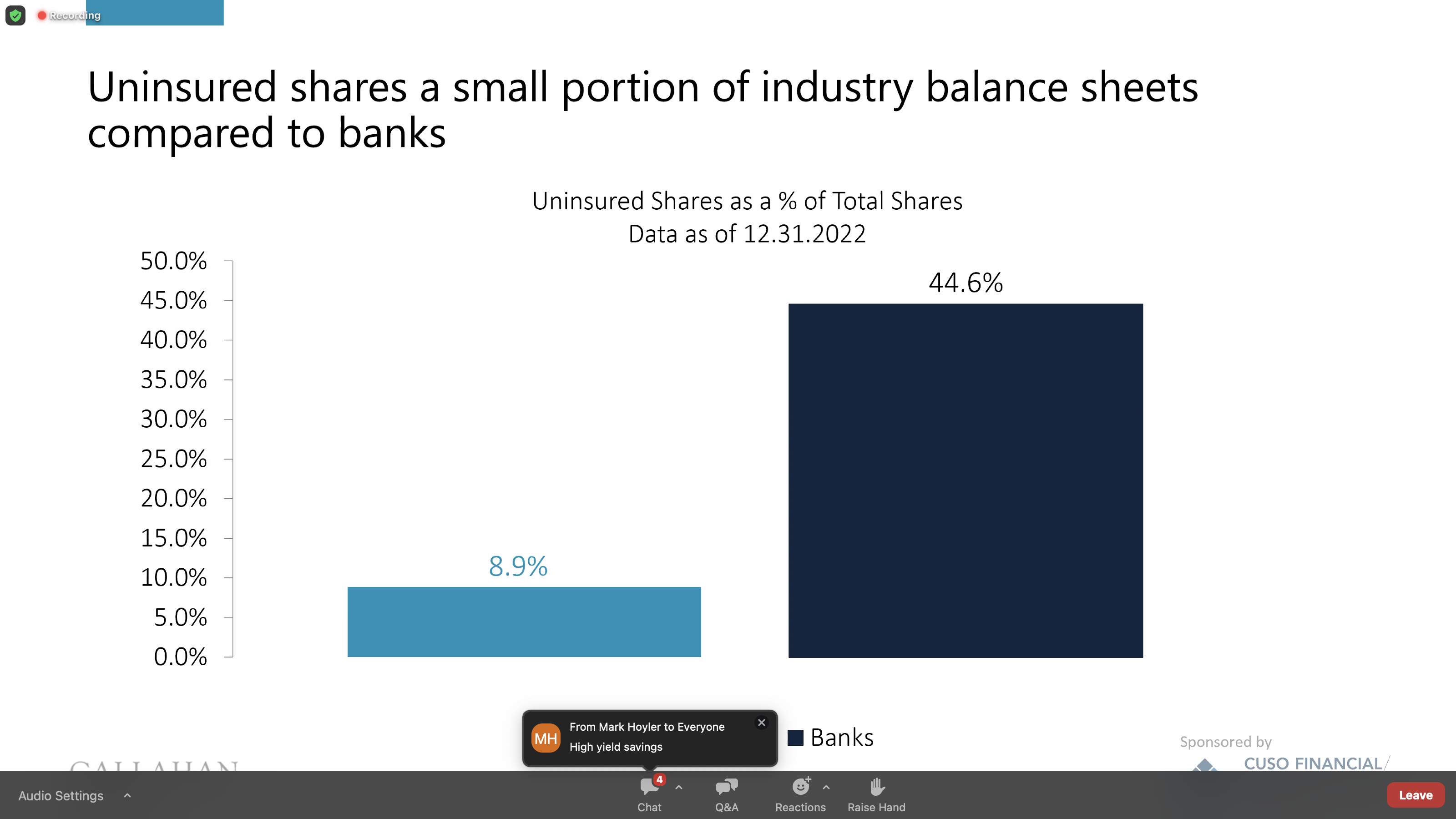

The first proof of this basic difference is that 92% of credit union savings are covered by NCUSIF, whereas only 44% of bank deposits were FDIC insured. This point was presented in Callahan’s Trend Watch analysis this week in the following graph.

The obvious Congressional question is why do credit unions need whatever changes FDIC might make if the balance sheet structures of cooperatives are fundamentally different from the banking industry?

- Politically it would seem unwise to request parity before any legislation has even been introduced. For in drafting any change Congress can easily respond to credit unions’ request with a simple bipartisan solution. They could mandate there be only one federally managed deposit insurance fund, the FDIC. That would be true parity. For the FDIC already merged the separate S&L FSLIC fund.

- The factual response to this Congressional possibility is that the NCUSIF is different in both structure and purpose from the FDIC.

Since the NCUSIF’s financial redesign in 1984 into a cooperatively-funded deposit model, credit union insurance has not required federal backing, even during the corporate crisis. By legislative intent, the NCUSIF is backed entirely by members sending 1% of every savings dollar to the fund. This capital base grows along with insured risk. This base provides sufficient revenue so that premiums are rare. That revenue option is a last resort and can be used only when Congressionally established financial levels are reached.

As a cooperative, the fund is required to pay dividends when reserves exceed the Normal Operating Level, historically 1.3%. The FDIC’s structure gives it only one means to cover increased risk—charge ever higher premiums on an expanded asset, not just the insured savings base.

- The two federally managed “insurance” funds have fundamentally different roles which reflect the character of the institutions they cover. The credit union model is a not-for-profit, member-owned consumer focused coop. This system has a much different purpose than the for-profit commercial banking model. The NCUSIF is also a source of temporary recapitalization to sustain a coop hit by uncontrollable financial events. In banking, the FDIC cannot provide assistance to private owners.

- CUNA and other credit union support for “parity “ with the FDIC could unfortunately be used to buttress Chairman Harper’s stated intent, from his first day on the NCUA board, to build a larger fund. His proposals would abandon legislative guardrails and add premiums as a regular option to expand the fund’s size relative to credit union risk.

There is nothing in the NCUSIF history that would support this desire for a larger fund. The Fund has performed though multiple economic cycles and financial crises that forced the FDIC to resort to multiple special premiums. The FDIC has no cap on how large its fund can be relative to its insured risk.

The downside of the NCUSIF’s financial success is that it has become a “piggy bank” from which NCUA draws increasing amounts to pay for its expanding operating budgets. Instead of paying for insurance losses, the majority of fund revenue is used for NCUA’s operating expense. This overhead transfer rate is currently 62.4 %, even though federally chartered credit unions are only 50% of insured risk.

The legislative constraints that are a part of the redesign passed in 1984 were to address credit unions’ fundamental concerns with an open-ended perpetual deposit underwriting commitment. The apprehension was: “If we just keep sending 1% of deposit to NCUA every year, what prevents them from just spending it.”

- If Congress were to change how FDIC insurance coverage is based, it won’t be a single action. Legislation will come with additional rules and regs, increased financials tests, and stronger regulatory powers for examiners and supervisors to mandate changes when deemed necessary. There will be a significant regulatory quid pro quo if coverage is changed.

Credit unions, who in their own analysis, say they are unlike banks, would become a part of this new regulatory avalanche. One need only think back to 1998 when bank PCA was mandated by the Credit Union Membership Access Act which had nothing to do with the Act’s primary FOM issue. But it was included, saddling credit unions with PCA (RBC/CCULR) requirements in 2022 that NCUA cloned from the banking regulator’s rules.

- Should credit unions individually or in certain circumstances believe additional share insurance coverage is desirable, options already exist. In Massachusetts, state charters must cover 100% of their savings. Amounts above the NCUSIF are insured by MSIC. In multiple other states, American Share Insurance offers additional coverage above the NCUSIF which credit unions can purchase. These are options credit unions can design to fit their own circumstances. NCUSIF insurance coverage is based on the principle that one size fits all.

- If the recent banking failures cause a change to FDIC coverage, one of the factors is the market accountability publicly traded banks face. Market short sales can convert temporary problems into more serious runs. Credit unions do not have this market accountability. They also are not required to have the same public transparency required in SEC 10-Q and other filings for shareholders.

An Opportunity to Demonstrate the Cooperative Difference

For credit unions the debate on insurance coverage should be an opportunity to substantiate the differences and soundness of the NCUSIF, and its extraordinary record of success since 1984. Before that time, the NCUSIF did follow the FDIC model. As an FDIC financial twin over two decades, the NCUSIF never came close to achieving the legislative goal of a 1% fund. This was even after using double premiums, the only option available, for several years.

A major risk to credit unions is a NCUSIF-managed Fund without an awareness by leaders of its differences and why these matter. The changes requested by Chairman Harper not only abandon the explicit legislative guarantees made to credit unions in return for their perpetual 1% underwriting in 1984. It would most certainly entail more FDIC look alike regulations.

Here is Chairman Harper’s request to Congress this week:

If Congress does decide to act in this area, the NCUA has two requests. The first is to maintain parity between the share insurance provided by the NCUA and the deposit insurance provided by the FDIC. Share and deposit insurance parity ensures that consumers receive the same level of protection against losses regardless of their financial institution’s charter type.

And second, if coverage levels are adjusted in any way, there will be costs associated with those adjustments, such as the need to increase reserves. Accordingly, the NCUA requests additional flexibility for administering the Share Insurance Fund.

Specifically, the NCUA requests amending the Federal Credit Union Act to remove the 1.50-percent ceiling from the current statutory definition of “normal operating level,” which limits the ability of the Board to establish a higher normal operating level for the Share Insurance Fund. Congress should also remove the limitations on assessing Share Insurance Fund premiums when the equity ratio of the Share Insurance Fund is greater than 1.30 percent and if the premium charged exceeds the amount necessary to restore the equity ratio to 1.30 percent.25

Together, these amendments would bring the NCUA’s statutory authority over the Share Insurance Fund more in line with the FDIC’s authority as it relates to administering the Deposit Insurance Fund. These amendments would also better enable the NCUA Board to proactively manage the Share Insurance Fund by building reserves during economic upturns so that sufficient money is available during economic downturns.

In sum, insurance parity is a false objective based on contradictory logic and a failure to understand the cooperative financial model. Credit unions should be careful what they wish for.

As one former NCUA Chair observed, the greatest threat to credit unions is parity.