In a news conference following the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, President Kennedy remarked: “Victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan. “

The SVB’s failure proves this adage untrue. The press and numerous pundits have already assigned multiple parentage: the CEO and management, the Fed’s rapid rate increases, regulatory and examination shortcomings, the external auditor’s clean opinion, the Silicon Valley customers $40 billion twitter run, Trump’s deregulation in 2018 and the Biden administration DEI policy objectives.

When everyone and everything is to blame, then no one is accountable. Just another “black swan” event. With more investigations/hearings to come, each new revelation will just add to the piles of condemnations. No lessons taken away. More regulations of course, for this is the default response whenever the barn door is left open.

A Spotlight on One Factor

From all these commentaries, I want to highlight one aspect that contributed to overlooking this risky situation. This factor has just become a part of the credit union regulatory eco-system.

In responding to my analysis earlier this week, Doug Fecher, the retired CEO of Wright-Patt Credit Union in Ohio, commented:

This situation makes me wonder if NCUA’s new “RBC” standards would have flagged the risks to SVB’s balance sheet. From what I can tell, much (most) of SVB’s investments were in “risk-free” treasury bonds and high quality agency securities, which in NCUA’s RBC formula would have earned some of the lowest risk multipliers.

To me it is another example of the folly of RBC-style risk management regimes … and why NCUA was wrongheaded in its pursuit of RBC.

This point of view is not limited to Doug’s observation.

During his time as Vice Chair of the FDIC, Thomas Hoenig challenged the agency’s reliance on risk-based capital requirements. He questioned both the theory and practice, pointing to the lending distortions which contributed to banking losses during the Great Recession.

He wrote about the SVB failure in this commentary:

The regulator apparently relied on the bank’s risk-weighted capital standard for judging SVB’s balance sheet strength. Under the risk weighted system government and government guaranteed securities are not counted as part of the balance sheet for calculating capital to “risk-weighted” assets.

This allowed the bank to report a ratio of around 16%, giving the appearance of strongly capitalized bank. However, this calculation failed to account for interest rate risk in its securities portfolio or the risk of having a highly concentrated balance sheet. It misled the public, and apparently the regulators.

In contrast, if the regulator had focused on SVB’s ratio of equity capital-to-total assets, including government securities, the ratio falls to near 8 percent; and if they had calculated the ratio as tangible capital-to-assets (removing intangibles and certain unbooked loses from capital) the ratio would have fallen to near 5%.

What this would have disclosed to the world is that the bank’s assets could not lose 16% of their value before insolvency but only 5%, a stark contrast.

Had the regulator not relied on the misleading risk-weighted capital measure, it might have take actions sooner. A simple capital-to-asset ratio, tells the regulator and public in simple, realistic terms how much a money a bank can lose before becoming insolvent. The regulatory authorities need to stop pretending that their complex and confusing capital models work; they don’t.

RBC and Credit Unions: A First Birthday

RBC became the surrogate capital ratio for all credit unions with assets greater than $500 million one year ago on January 1, 2022.

Before this in a September of 2021 analysis, Why Risk Based Capital is Far Too Risky. Hoenig is quoted:

“A risk-based system inflates the role of regulators and denigrates the role of bank managers.

We may have inadvertently created a system that discourages the very loan growth we seek, and instead turned our financial system into one that rewards itself more than it supports economic activity.”

RBC and Asset Bubbles

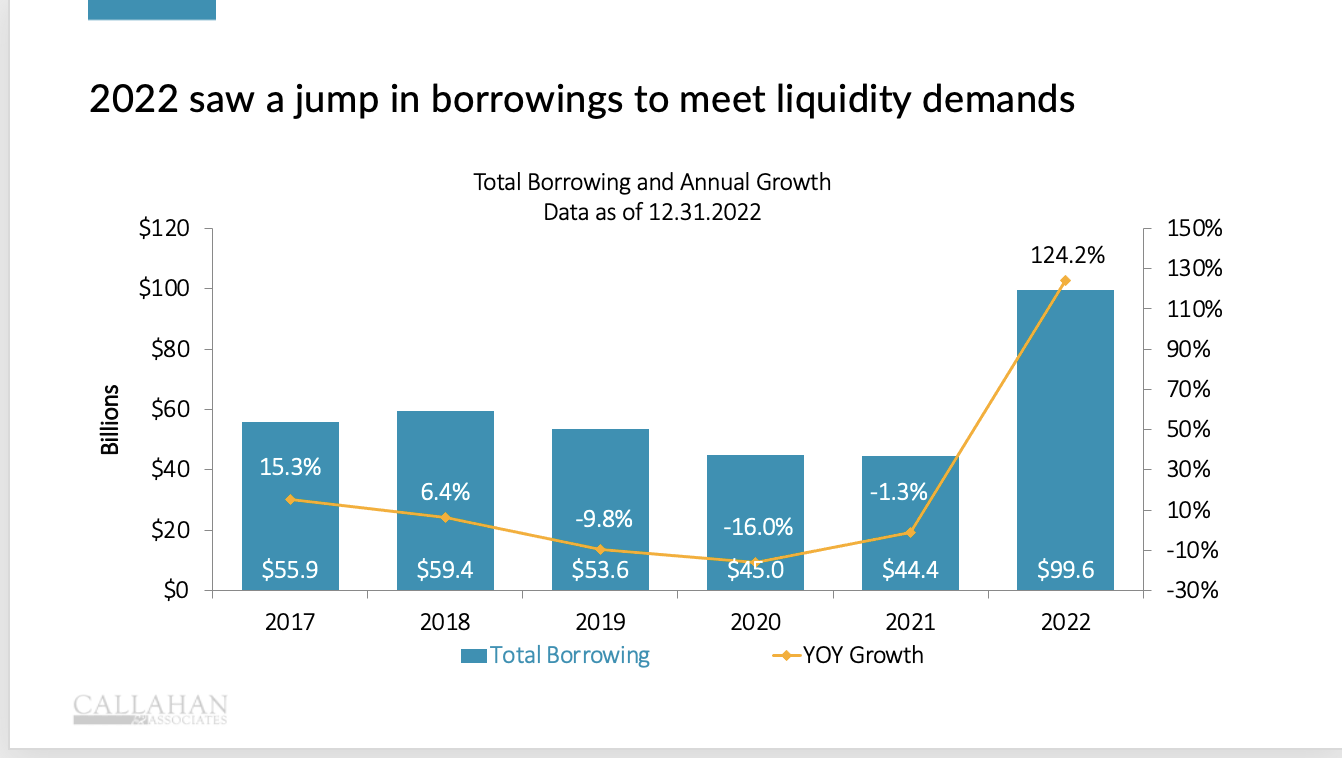

Shortly after the critique of regulatory incentives induced by risk weighted assets, in Asset Bubbles and Credit Unions (JANUARY 10, 2022) the consequences from potential Fed tightening were noted:

When funding looks inexpensive and asset values stable or rising, what could go wrong?

The short answer is that the Fed’s inflation response will disrupt all asset valuations and their expected returns.

The distorted results caused by RBC was presented in Credit Unions & Risk Based Capital (RBC): A Preliminary Analysis in February of this year. Among the findings:

The 304 credit unions who adopted RBC, manage $822.7 billion in assets. But the risk weighted assets total only $479 billion. That 58% ratio is the NCUA’s discounting of total assets total by assigning relative risk weights. and,

One credit union with assets between five and ten billion dollars, reports standard net worth of 12.5% and an RBC ratio of 48.3%.

This February analysis using June 2022 data of RBC credit unions showed that:

250 of these 308 credit unions reported unrealized declines in the market value of investments that exceeded 25% of net worth. Four credit unions reported a decline greater than 50% of capital. This was before the five additional Federal Reserve’s rate increases through the end of the year.

RBC’s primary focus is credit risk, the loss of value from principal losses from loans or other assets. Balance sheet duration mismatch is not captured as are other common management errors: concentration in either product or market focus, limited or no diversification of product or market, or just simple operational mismanagement.

These common challenges become amplified by insufficiently considered non-organic growth forays such as third party loan purchases or originations. Whole bank acquisitions are an example of such risks often accompanied (disguised?} by growing amounts of the balance sheet’s intangible asset, goodwill.

The RBC proxy indicator for safety and soundness creates a distorted impression of real institutional risks. Managers learn to game the system so that boards, members, and regulators fail to understand the institution’s total financial situation.

And when along comes a change in underlying assumptions, like the Fed’s rate increases, the previously unrecognized vulnerabilities quickly appear.

RBC creates for some institutions a theoretical capital ratio that is nothing more than a “regulatory house of cards.” SVB will not be the last example.

As Doug Fecher recommended in his 2016 comment letter on the proposed rule, “RBC should be a tool, not a rule.”

To his credit, Kennedy learned from the Bay of Pigs misjudgments when the Cuban missile crisis occurred in 1962.