What does the fate of bananas have to do with credit unions?

In 2016 BBC news reported on the potential death of the world’s favorite fruit:

For decades the most-exported and therefore most important banana in the world was the Gros Michel, but in the 1950s it was practically wiped out by the fungus known as Panama disease or banana wilt.

Banana growers turned to another breed that was immune to the fungus – the Cavendish, a smaller and by all accounts less tasty fruit but one capable of surviving global travel and, most importantly, able to grow in infected soils.

Do we need to worry about banana blight?

The story was updated in 2019 when the Cavendish itself became subject to blight:

While there are more than 1,000 varieties of bananas, which come in different colours, shapes and sizes, just under half of global production is the Cavendish type. While the fungus is not harmful to humans, it has the potential to eventually wipe out Cavendish bananas, according to experts.

Millions of people around the world rely on bananas and plantains as a staple food and as a cash crop.”The potential for devastation if it does reach them is almost total.”

“The world would carry on if we lost bananas but it would be devastating for those who rely on it economically and very sad for those of us who enjoy eating them.”

The Fungus Problem

The disease is “a serious threat to banana production” because once it is established, it can’t be eradicated, the UN says. And fusarium fungus can remain in the soil for 30 years.

It has been spreading for decades through Asia, Australia and Africa. It has now been detected in Latin America, which supplies the bulk of the world’s bananas grown for export. No other types of banana are yet ready for cultivation on a commercial scale.

If one plant is susceptible to a disease, all of its offspring will also be susceptible.

Monocultural crop

The Cavendish was brought in as a monoculture crop after “banana wilt” all but wiped out the world’s previous favourite dessert banana, the Gros Michel, in the 1950s.

According to Prof Kema, the main problem stems from the over reliance on Cavendish varieties for export, which he describes as a “monoculture”.

“We have to diversify banana production,” he said. If there is only one type of banana plant being grown, resistance to infection is lower.

There are trade-offs between the costs of containing it and the profits from growing bananas, he said.

Small producers may not be able to afford the mitigation measures, he added.

People in the UK eat 10 kilos of bananas per year, on average, or about 100 bananas.

So the market is there, but will Cavendish bananas be in the future?

The Credit Union Lesson

The critical issues in the potential extinction of this popular banana product include:

- The need to diversify the varieties of bananas grown;

- The tradeoffs between costs and benefits when fighting the fungus;

- The disadvantage of smaller producers when using mitigation efforts;

- The monocultural approach to new varieties;

- The time needed to cultivate new strains;

- The consumer need remains, but will there be an option?

In just 120 days NCUA’s oft-deferred RBC rule takes effect, unless the board acts.

The agency’s Risk Based Capital rule has every issue associated with the banana example. A single risk assessment applies to all firms; the lack of cost- benefit analysis; new approaches are discouraged; and credit union are encouraged to follow a “monocultural approach” to business practice. Buy a bank here, merge a credit union there, and embrace the isomorphic actions of one’s peers to hide in the crowd.

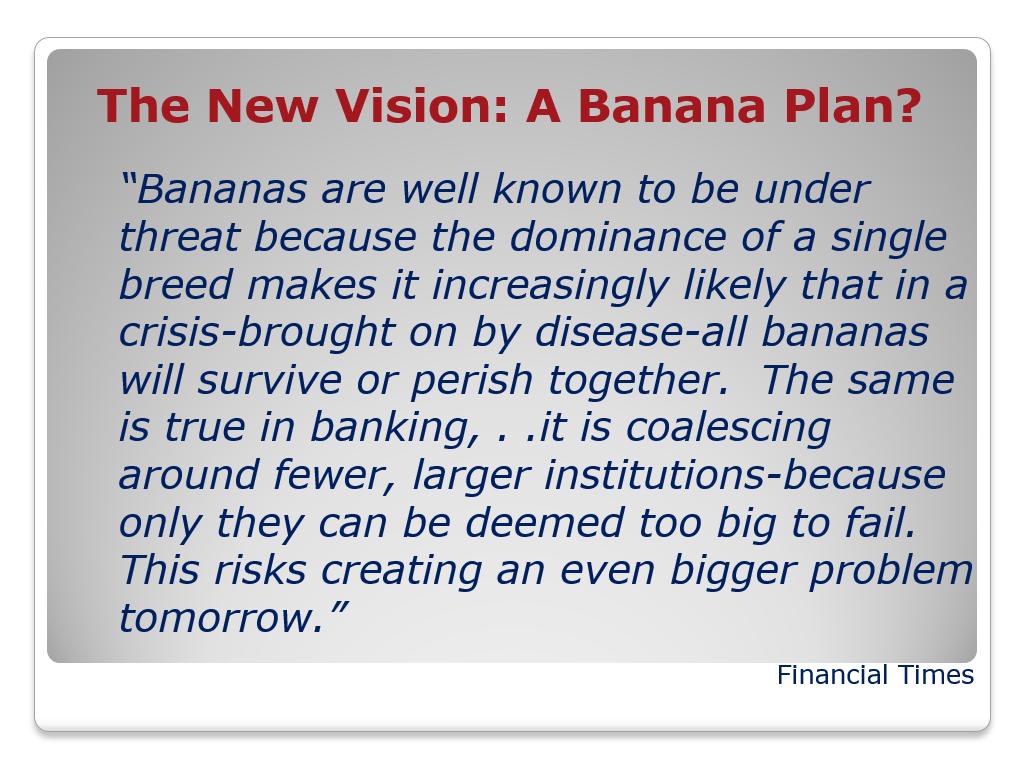

If you question the banana parallel, the Financial Times printed the following assessment about how the US banking problems had been “resolved” during the Great Recession:

Will credit unions following NCUA’s RBC rule become another example of a banana plan? Or will common sense prevail before the January 1, 2022 deadline?