Most credit union observers agree that the emergence of financial cooperatives was one outgrowth of the reform movements affecting many areas of American society at the beginning of the 20th century.

Across America, factory workers, farmers, women suffragettes, and city social workers had organized numerous initiatives and political efforts to resolve emerging problems. These initiatives responded to individual abuses and inequalities that became exacerbated during this era of monopoly capitalism converting a largely agrarian economy to an industrial one.

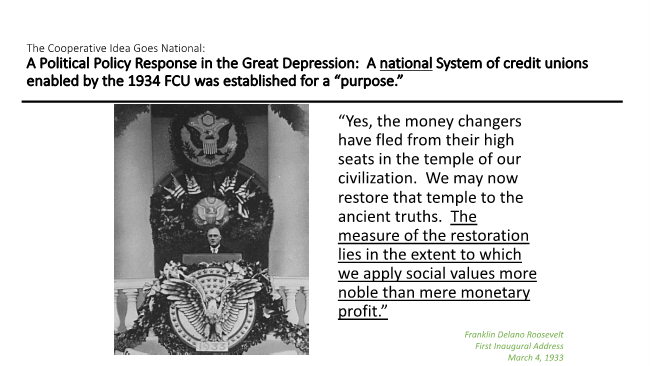

Credit unions were one of many attempts to meet the basic financial needs of ordinary people who had no access to fair financial services of any kind. This experiment begun with St. Mary’s Bank in 1909, then slowly evolved state by state over twenty-five years. These various examples became the proof of concept that resulted in the passage of the Federal Credit Union Act in 1934 as part of FDR’s new deal initiatives.

Filene and Bergengren convinced the administration and Congress that a national program for expanding consumer credit could help with recovery during the depression by increasing demand for consumer goods and services with credit.

The following slides provide snapshots of the evolution of the “movement” from social initiative to a fully formed financial system alternative for consumers. They summarize the ever changing balance between mission/purpose and institutional financial success as overseen by the federal regulator.

- The Need for Fair Consumer Credit

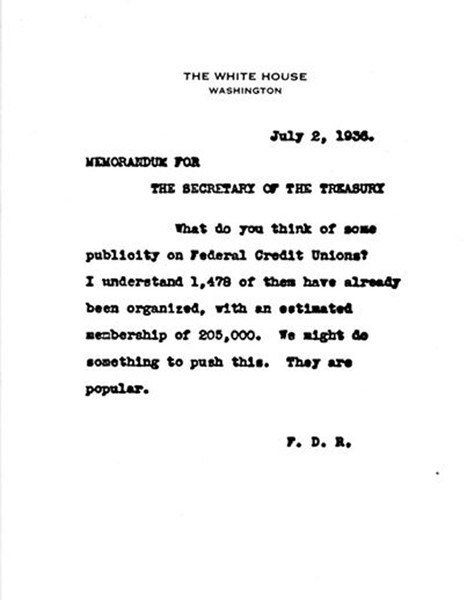

- Roosevelt’s support. 4,793 federal charters were issued from 1934 through 1941 when new charters fell temporarily to around 100 per year during WW II.

- Credit unions were first overseen by the Department of Agriculture. During WWII oversight was transferred to the FDIC. Post war, the bureau of federal credit unions became a department within HEW. In 1977 the National Credit Union Administration became an independent agency.

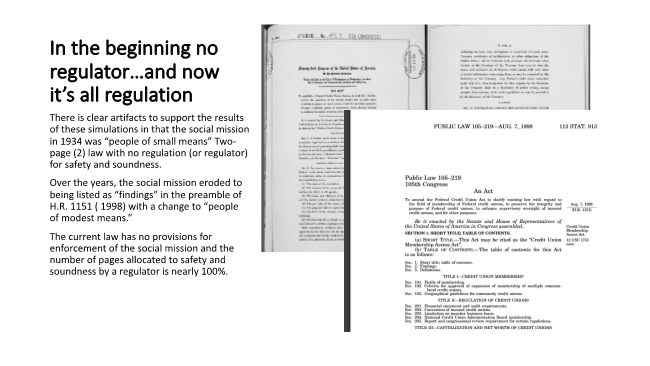

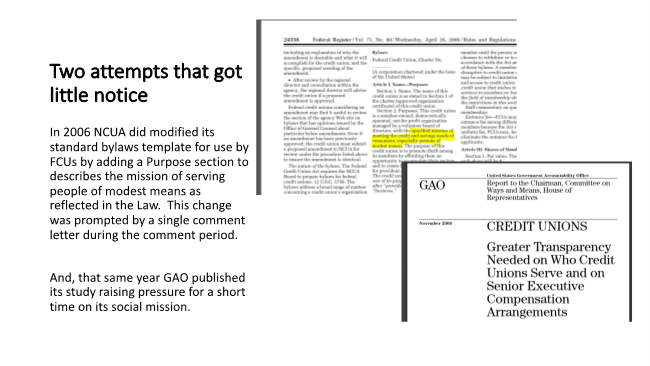

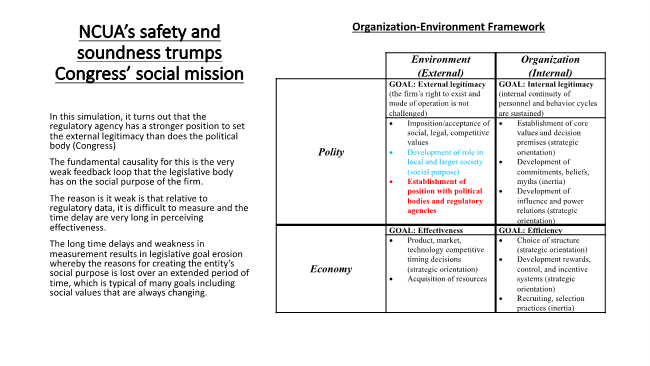

- In 1977 NCUA’s independent status began with 13,050 active federal charters. At the end of 2020 there are 3,185 active federal credit unions. Of the 24,925 federal charters granted, 92% were issued in the forty-four years prior to NCUA’s becoming an independent regulatory agency. Under NCUA the balance between mission/purpose and economic performance has increasingly focused on financial performance.

- Today NCUA’s safety and soundness measures dominate cooperative oversight.

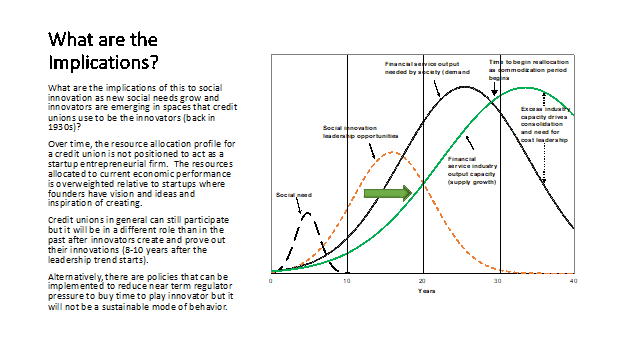

- The absence of new charters has stifled entrants with innovative ideas. The industry has consolidated and become more homogeneous in business strategy.

Slides: 3-6 are by Steve Hennigan, CEO of Credit Human FCU using feedback loop analysis.

The traditional view of credit union’s special role justifying their tax exemption has three bases: their cooperative, member-owned structure, the legislative intent to serve people left behind by existing financial options, and the field of membership-common bond-requirement.

As the cooperative business model has evolved, so has the concept of purpose and credit union’s role in their communities. Today member’s financial health is an animating concept for some. Other credit unions continue emphasis on superior service, better value, and member relationships.

Consumer financial services are now available from multiple providers. Credit union’s success confirmed that consumer lending is an attractive business opportunity for banks and other start up firms. Today many financial options and new entrants, from payday lenders to online lending startups, target consumers.

More than a Business Model–A Design Advantage

The founding pioneers of credit unions did more than prove out a new business segment with consumers. The cooperative model was one in which people:

- Found a solution by working together;

- Identified common challenges to organize and solve it themselves;

- Prioritized mutual needs overcoming fears that they couldn’t succeed;

- Created a community and bond that formed relationships to sustain efforts;

- Accomplished something they had never done before to get something they didn’t have.

Cooperative purpose established these core traditions that are the foundation for continuing credit union relevance and uniqueness in an ever-changing economy.

The question is, if credit unions did not exist, would we create them today? What needs would they serve? Is purchasing the assets and liabilities of banks, consistent with the credit union cooperative role?