As consumer focused financial providers, changes in local employment patterns can have a profound impact on members’ and their credit union’s financial outlook.

Credit unions have always walked toward members and communities in difficulty, not away. The importance of a local credit union option is especially critical for those living in areas of slower growth and/or lower paying job opportunities. Now a study has tried to identify those cities whose economies trail national averages.

In the FDIC’s Second Quarter report, there is an article U.S. Industrial Transition and Its Effect on Metro Areas and Community Banks (pgs 45-74).

The study covers fifty years from 1970-2019 in the shifting employment patterns from higher paying industrial occupations, such as manufacturing, to an economy based on service industry and technology.

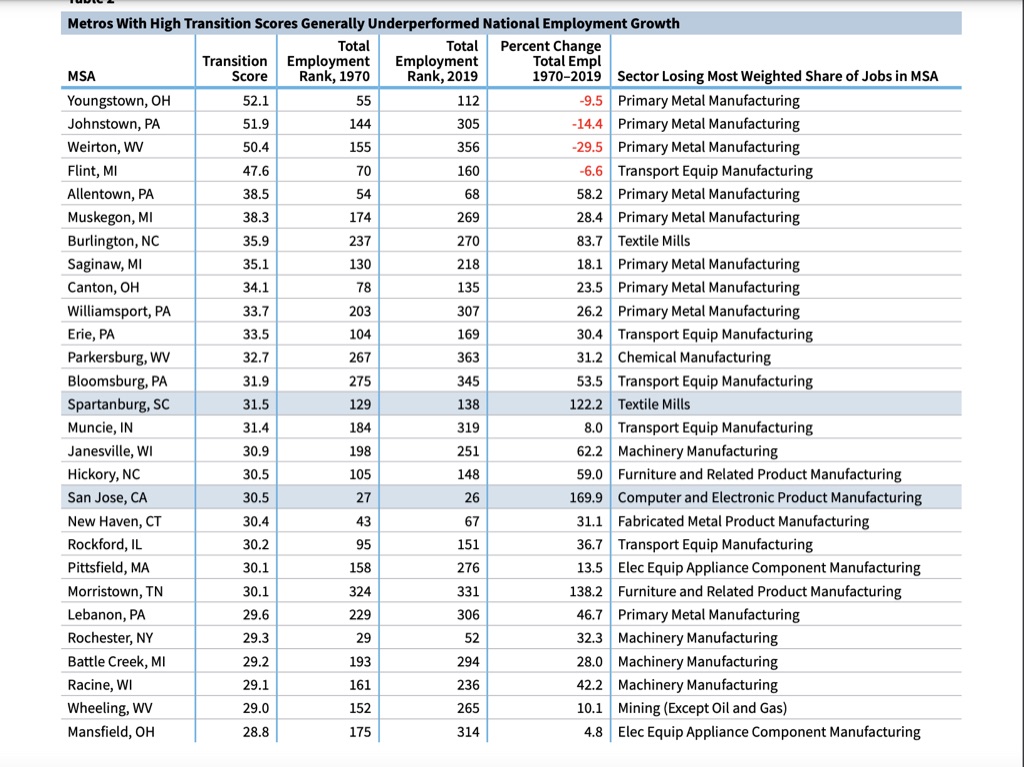

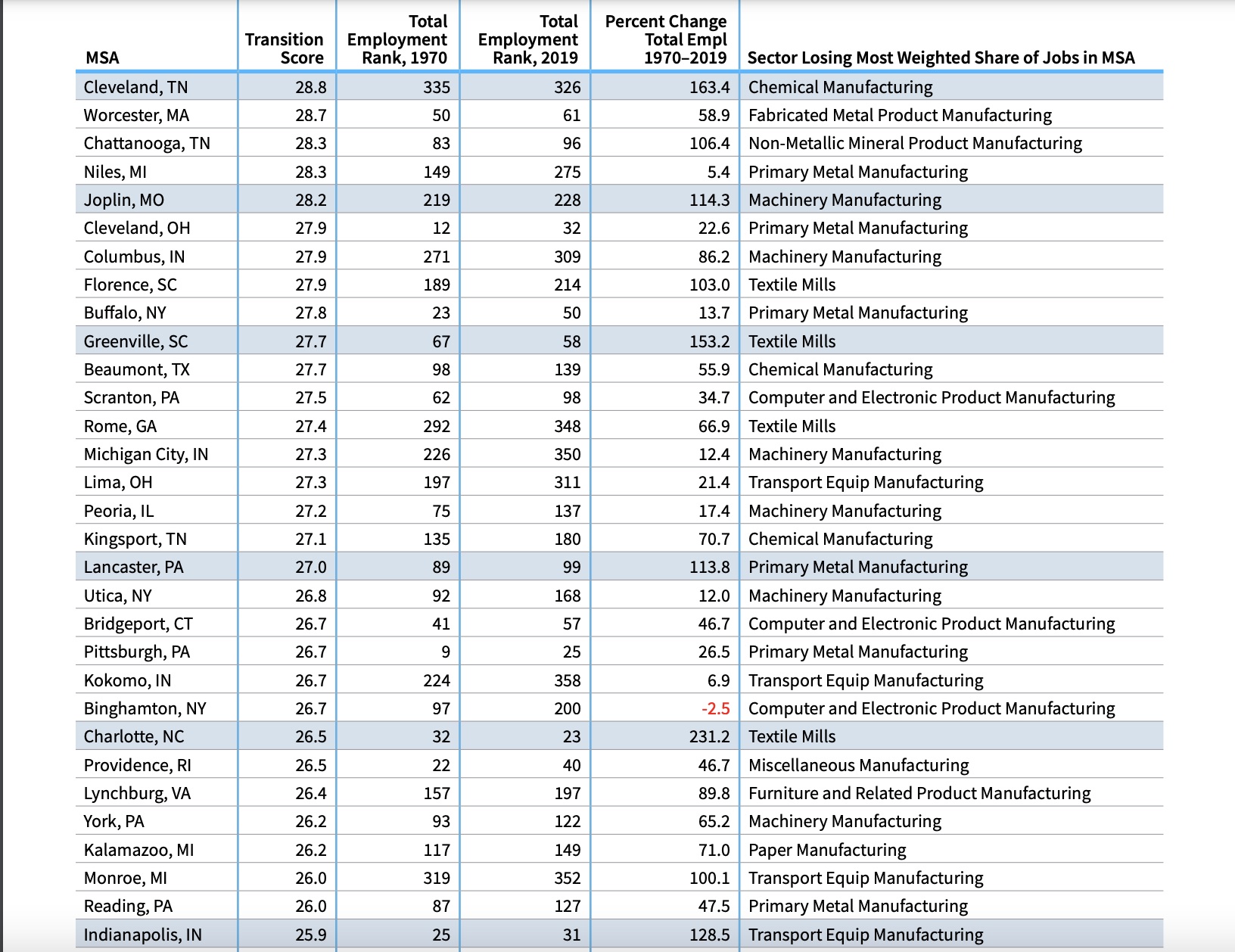

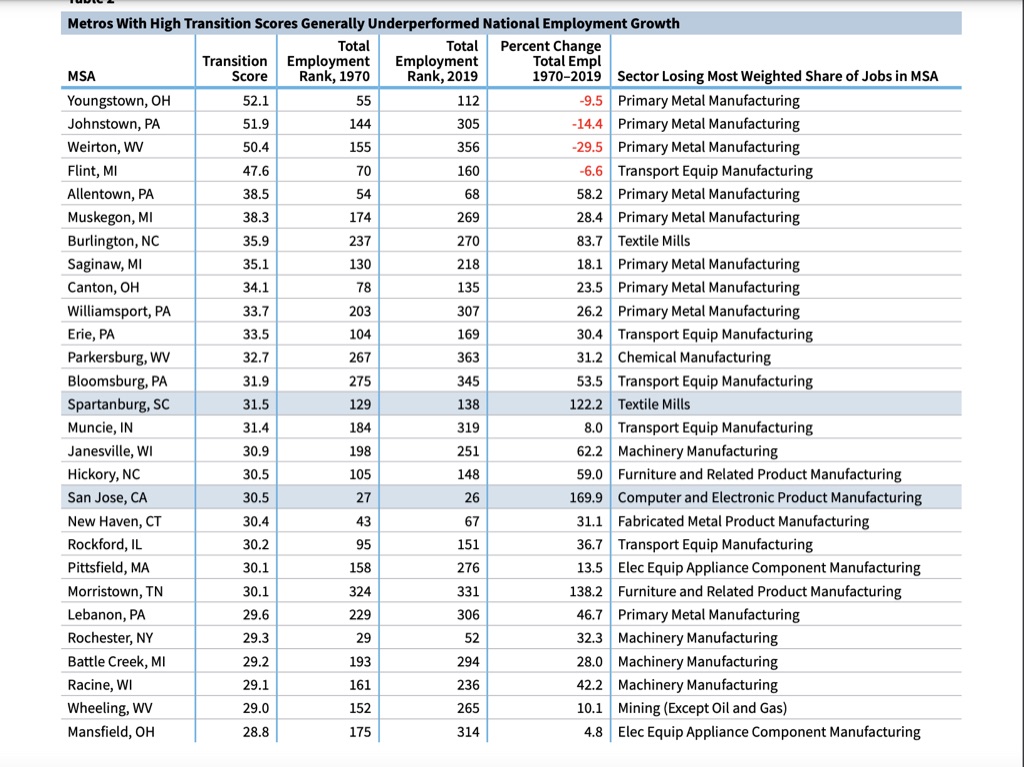

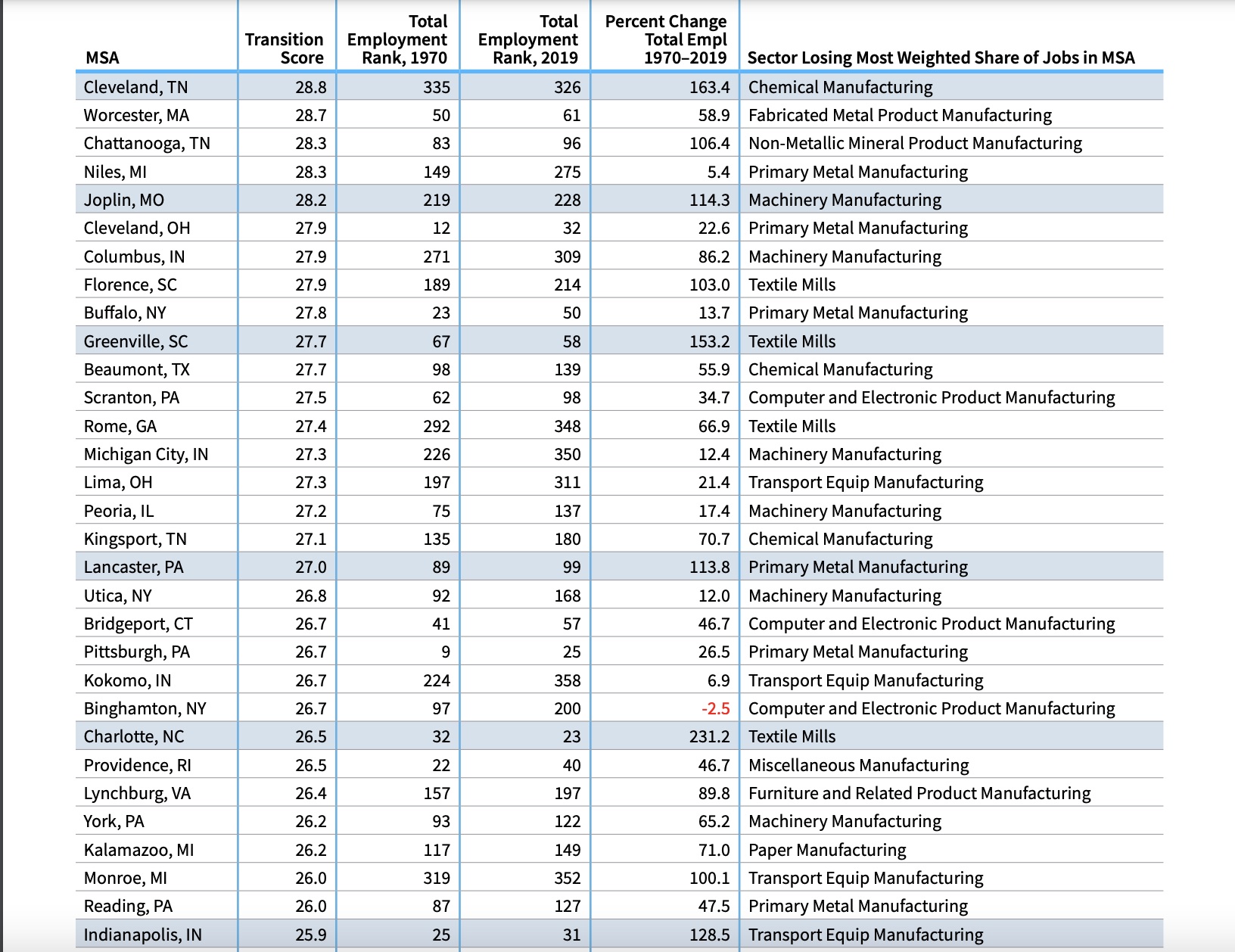

The study uses Metropolitan Statistical areas (MSA’s) and developed a “transition score” for ranking the areas showing those most impacted by the decline in higher-paying to lower-paying employment.

Of the country’s 387 MSA’s (cities over 50,000) those with higher transition scores had slower economic growth, were mostly smaller in population, and located in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. The two study tables below show the MSA’s with the highest employment transition scores along with the change in total employment over the past fifty years.

Of the 54 MSA’s in states with the highest number transition scores, Pennsylvania led the states with ten.

(note: for highlighted MSA’s above the study presents analysis of each showing why they reported high population growth)

Additional tables and graphs illustrate both the distribution of the highest scores and the lower impact scores among the largest MSA’s which tend to have a more diversified industrial employment base (table 3 page 55).

As one would surmise, MSA’s with high employment transition scores had slower income growth than the nation as a whole. (chart 4, pg 57)

In the four metro areas with the highest scores above, there were a number of other negative economic factors in addition to the erosion of manufacturing. These included total employment and population declines, slower per capital and GDP growth versus national averages, natural disasters and a lack of amenities such as universities and favorable weather.

Impact on Community Bank Performance

The report’s final pages analyze the performance of banks whose headquarters were in one of the 54 MSA’s with the highest transition scores, that is communities impacted by the greatest change in employment patterns. Following are some of their conclusions.

While overall performance is generally lower, these banks performed better than other community institutions in periods of high economic stress. In terms of structure, consolidation occurred as in the industry at large, such that only 31% of high transition communities were left with a local institution by 2019. New charters were less frequent in these MSA’s. But bank failure rates were lower.

In the highest transition scored MSA’s, banks had weaker branch and deposit growth, slower overall financial activity including pretax ROA.

The reason for these banks better performance during the two periods of economic crisis, was that their balance sheets contained more single family residential loans and lower exposure to commercial and industrial loans than institutions located in a less impacted MSA’s.

The Takeaways for Credit Unions

Credit unions are no strangers to changing employment patterns in their market areas. Many were originally chartered with employer based FOM’s. The deregulation of the early 1980’s allowed both state and federal charters to diversify their member base and seek other growth options.

The banks that were most resilient during these employment transitions focused more on first mortgage lending and less on commercial. Credit unions are almost exclusively consumer and real estate focused lenders. Even when an industry or local employer closes, the members tend to stay local. And need their credit union more than ever.

The study shows the external context matters in overall performance. It shows the obvious–that slower economic growth tends to correlate with lower financial performance. It also reinforces the critical and crucial role locally-focused financial firms have in these community transitions.

There is a cyclical pattern in much economic change. A high growth area becomes crowded, expensive, and loses appeal versus communities with lower home prices and more stable institutions. The role of credit unions as local economic actors is vital in both communities.

Many commentators suggest the latest election outcomes were driven by voters’ dissatisfaction with their economic situation, especially inflation.

Credit unions have the chance to take the lead in giving these members a hand up.

As other firms may rush to the high growth market attractions, the study shows that sustainability in times of deep transition is not only possible, but critical to the bringing the time closer when good fortunes return.