A Call to Action and a Test of Who Credit Unions Are

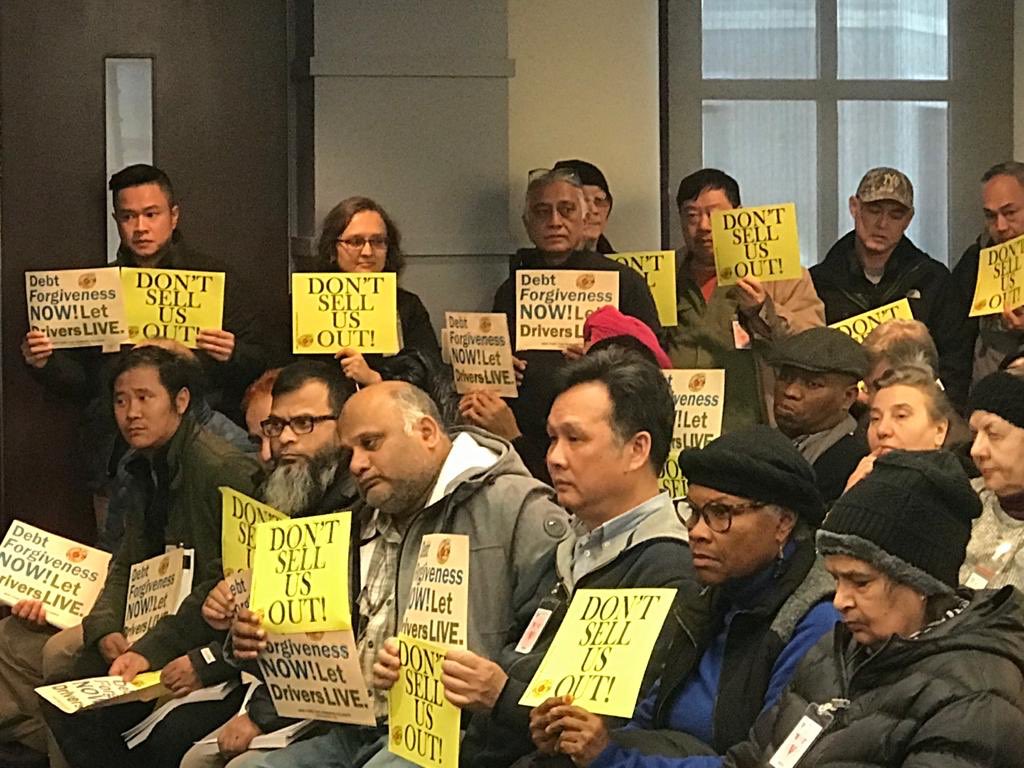

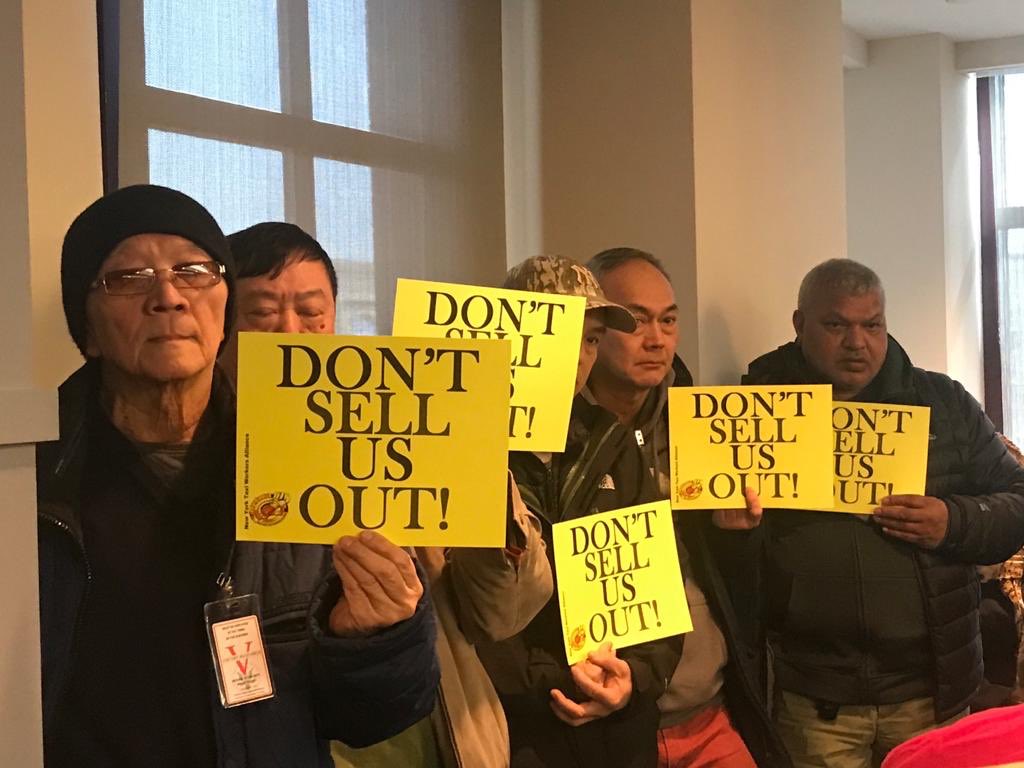

This photo is shared with permission from the January 23, 2020 NCUA board meeting courtesy of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. http://www.nytwa.org/

What are these members telling us? Why has no one listened to them before? More crucially, why did these borrowers show up at an NCUA board meeting?

Member frustration and hope are on display. Throughout the taxi medallion disruption NCUA from top to bottom has turned a deaf ear to the needs of the member-borrowers.

This neglect has been pointed out time and again in letters to the NCUA Board, in articles in the New York Times, and in the stories from members to the press. Now there is a last opportunity to do the right thing. And to demonstrate the credit union difference.

A Thousand Words

A Feb 5, 2019, an article on creditunions.com described NCUA’s ineffectiveness in its oversight of the taxi medallion disruption. The article asked: The Taxi Medallion “Resolution” Works In Whose Interest? Following are excerpts from one year ago:

. . . .The critical question is not what the normalized the value of the medallion asset might be, but how does a credit union manage through a business disruption to sustain operations? The NCUA’s response was to eliminate the impacted credit unions through liquidation, purchase and assumptions, and forced merger. And in the end, to charge credit unions $744 million for “washing its hands” for oversight.. . .

This raises two questions: Did the NCUA act in members’ best interest? And is the $744 million liquidation expense the wisest use of credit union money?

Who Is The NCUA Really Helping?

The traditional approach of share insurance is to ensure the safety of member savings for all amounts less than $250,000. But in a credit union, the interests of the borrowers should also be considered and treated with the same or even greater respect as those of savers.

Credit unions were not designed primarily as savers clubs. Consumers have multiple options for safely saving money, insured and uninsured.

Credit unions were formed to address borrowers’ needs. Taxi medallion financing was not only a community service but also an ideal example of cooperative finance. A lot of people — many of them immigrants making their way in a new country — financed their American dream through taxi driving and then medallion ownership.

When the security that underwrites a loan is devalued, both the borrower and the institution suffer. When the security is an income-producing asset, such as a taxi medallion, the impact on both is even greater. Both income prospects and accumulated value are hurt.

Whatever the security for a loan, a lender’s successful transition through a crisis depends on its willingness to rewrite terms, lower payments, and recognize the borrowers’ efforts to find other income and/or to persevere in current circumstances. This is what credit unions did repeatedly for home and auto borrowers during the recent Great Recession. Cooperative design makes this patient, member-focused adjustment process possible.

The Broken Bonds Costing $500 Million

Conservatorship is an important regulatory option for sustaining the institutional framework as a credit union works through problem assets (loans or investments) whose future value is uncertain. But if regulatory problem-solving becomes merely a “fire sale” to dispose of problem loans, then the bond between the borrowing member and the credit union is broken. The future for both becomes problematic and the options for positive, mutual solutions much reduced.

The NCUA conserved Melrose and LOMTO credit unions in February 2017 and liquidated them 18 months later. When these conservatorships were terminated, the opportunity to preserve value, and assist members, was destroyed..

LOMTO and Melrose reported their June 30, 2018, financial condition under NCUA management as a combined deficit capital position of $155 million. When liquidated within months of that filing, NCUA recorded a $744 million expense. This $500 million difference shows the cost of giving up all future value from working with members. Resolution becomes “cutting and running” away from members’ problems rather than using cooperative design advantages to resolve them.

A Request to the NCUA Chair

NCUA’s ineffective oversight undermined the relationship between the credit unions and borrowers so much that the president of the Committee for Taxi Safety wrote NCUA chair McWatters on May 12, 2017, about the agency’s shortcomings:

“For the most part medallion owners are not seeking to walk away from their loans. They are not seeking to walk away from personal liability. Recognizing this, lenders have stepped up to meet this challenge and work with medallion owners. … The only lender that is refusing to work with medallion lenders is Melrose, under the control of NCUA. Regardless of each owner’s outstanding debt, the NCUA has taken a hard-line, one-size-fits-all approach that demands massive up-front principal pay downs of several hundred thousands of dollars and/or mortgages on residences to renew loans.

“Even if the borrower complies, the NCUA then seeks to substantially increase the interest rate on the loans. Melrose has taken borrowers who want to pay and placed them in a position in which they know they will be put in default, thereby forcing them to face financial ruin. …

“The NCUA’s position is so extreme that it has told borrowers who are current on their loans and still making all payments, that if a medallion is in storage for any reason, temporarily or long term, that it will immediately commence foreclosure proceedings. …

“All we are asking is for the NCUA to act reasonably and allow struggling medallion owners some flexibility in paying off loans. … The NCUA’s behavior has been that of a bully. … It is time for the NCUA to end this assault on our industry and show leadership and human decency.”

Transferring Loans to an Outside Servicer

The best estimates implied by call report data are that all credit unions now hold more than 8,000 member loans secured by taxi medallions. The average outstanding loan is between $250,000 and $350,000. Many of these borrowers will be financially challenged as self-employed driver/ debtors. Like others working in the so-called gig economy, their future is not certain. Will credit unions work with these borrowers as members, or will the regulator and its agents try to rid themselves of any responsibility for these member-owners?

The NCUA transferred Melrose’s medallion loans to an outside servicer. . . The borrowers now have three options: pay, go delinquent, or walk away via bankruptcy. Without an interested lending partner holding the loan, rewrites or other refinancing accommodations are lost. There is no prospect of a future relationship. The credit union promise to member-owners is non-existent. Selling problem loans is how banks, not coops, routinely solve their problem credits.

Although written one year ago, the article shows why the borrowers came to the NCUA, not the FDIC’s board meeting last week.

Where We Are Now: NCUA Largest Holder of Taxi Medallion Loans

Newspapers reported NCUA’s intent to sell in the open market its portfolio of loans acquired from its liquidations. Last week a New York city councilman announced a multi-pronged effort to stabilize the taxi industry including creating a mission driven, nonprofit entity to purchase the loans at a discount and then pass the lowered obligation through to borrowers CUNA and three leagues wrote NCUA on January 22 requesting that NCUA delay a liquidation sale due to harm it would cause borrowers, even those who are current in payments, and to credit unions still holding loans but whose collateral would be devalued in a fire sale.

NCUA working in collaboration with credit unions, leagues, CUSOs and New York taxi regulators, has the chance to create a cooperative solution that would help thousands of member-borrowers and set break from its past neglect. One NCUA board member called the drivers’ attendance “democracy in action.” But democracy only works if those in positions of authority respect their constituents by supporting collaborative solutions, versus selling out to financial bargain hunters seeking to maximize profits out of the misfortunes of others.

A Message: Who Does the Credit Union System Serve?

Read more:

CU Times: Amid Urgent Calls for Help, NYC Taxi Medallion Task Force to Meet With NCUA Officials

NY Times: New York Is Urged to Consider Surge Pricing for Taxis