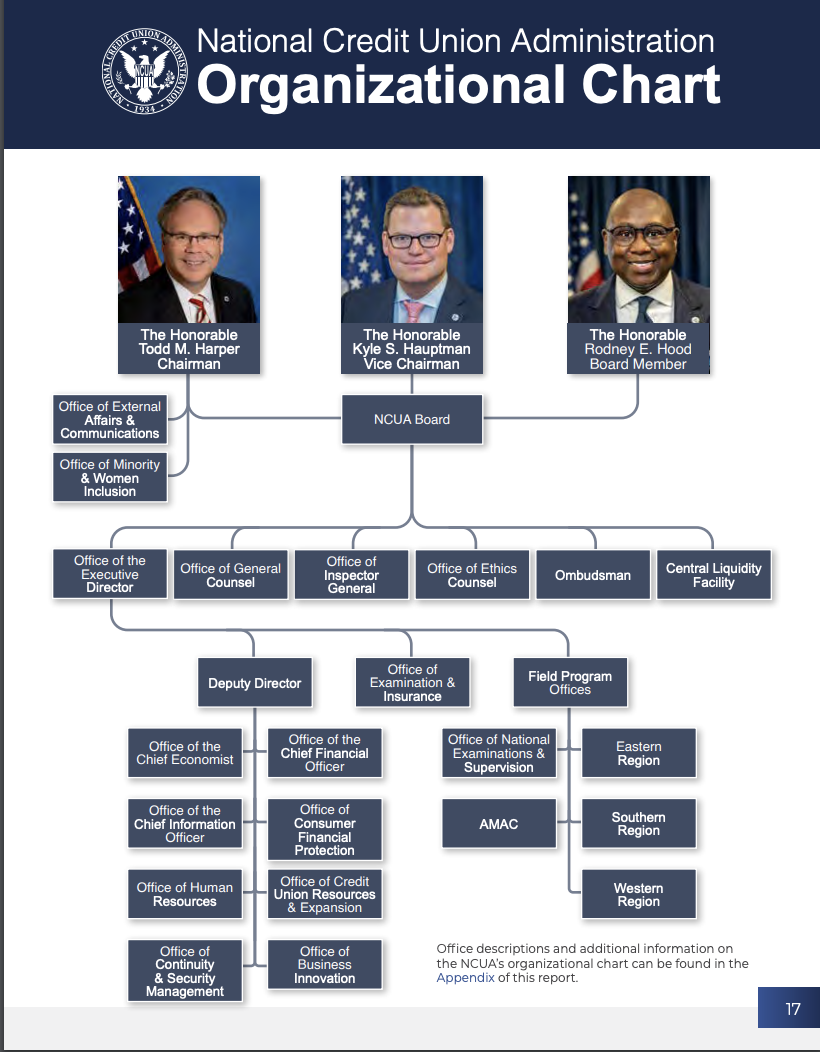

On June 1, 2025 Thrivent FCU converted to a state issued Industrial Loan Chatered (ILC) bank with FDIC insurance. There are only 24 such charters operating in the US,

The process took three years and had to be approved by the credit union’s member-owners with at least 20% voting on the change.. The conversion resulted in the full payout of the members’ collective equity, plus a bonus dividend on shares. The full details are reported in the post Thrivent Members Approve Sales to a Bank.

Thrivent Bank’s Sponsor

In its June 2 launch announcemnt, Thrivent Bank reported $1.09 billion in total assets. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of Thrivent Financial.

The parent company,Thrivent Financial for Lutherans, is a member-owned, fraternal benefit society. It is a non-profit , managing over $193 billion in administered assets, with a tax exemption based on religious affiliation.

According to Thrivent Financial’s 2024 Annual Report, it holds $18 billion in capital and serves 2.4 million members. Its primary products inlude insurance, annuities and health care programs. The Report has statistics on its community contributions and volunteer efforts.

The parent company’s CEO said the new charter: “combines our legacy of trusted financial advice with a modern, client-first banking solution. Thrivent Bank will help us build relationships with younger clients earlier in their financial journeys – who we can then serve throughout their lives.”

The New Bank’s Strategy

In a November 12, 2025 interview with a Banking Dive reporter, the CEO outlined his focus. The conversion “aimed at broadening the financial institution’s reach nationally and attracting new clients.”

Located in Salt Lake City, the bank is digital only with no branches.

The CEO. Brian Milton’s value proposition is to combine its digital platform with live personal advice and the financial expertise of the Thrivent organization: “everything that we see out there seems to be having to pick one of those two,”

The new web banking platform is still under construction. The current site provides a fairly standard listing of consumer services. Savings rates would appear to be at the lower end of the market. Auto loan rates are based on a matrix of model year and loan term.

The bank’s business financial services appear targeted to the non-profit sector:

It takes organization, planning, passion and vision to run a business, church, school or charity. It also takes the right financial institution to help you navigate the nuances of business and nonprofit banking. Whether you’re a new or established business, church or foundation, business banking tools from Thrivent Bank will help you every step of the way.

The one unique prodict focus would be its specfic contact center for studen loans.

A Strategy Combining the Best of Credit Unions and Banking

The web site is still under construction so there is not a lot to see at this time. The CEO stated the bank would rely on ouside vendors to meet its technology (presumably digital banking) solutions.

The banking charter gives the possibility of national reach for younger geneations of retail customers. Those at the beginning of their financial lives may not be the sponsors prime target for insurance products today. Rather loans may be their first financial need along with basic transaction services.

The bank’s differentiation will be personal service: “We’re not going to be putting bots in front of clients, The human piece is extremely hard to replace.” This approach is called “purpose based advice.”

The de novo has a lot going for it. A 120-year old non-profit financial sponsor-owner with deep pockets; the experience and start up relationships from the credit union; and a philosophy of service seeking life-long member relationships. It has an affinity client base from the parent as an initial focus.

The critical question is whether a digital only delivery strategy can effectively compete with local, personal credit union service centers staffed with experienced personnel. Being present in and an active part of the communities served is both the foundation and special advantage of credit unions.

Digital offerings for most credit unions, compliment but do not replace the option for in-person service. And community presence and involvement. In the few cases where digital-first is the primary go to market effort, those credit unions are struggling compared to the performance of their more grounded peers.

The Thrivent Bank is very unlikely to fail. The real question is how successful the digital only strategy will be? And at what cost to create a clear value advantage for users? Especially in a virtual world where options are just a click or AI search away?