This is second of five articles is to assist credit unions responding to NCUA on the capital adequacy (NOL) of the NCUSIF due July 26. The first article quoted Chairman Todd Harper’s unsubstantiated view that NCUSIF’s structure is inadequate and requires more NCUA authority to assess premiums.

This article reviews the accounting changes, beginning in 2001, that reduced NCUSIF dividends and increased expenses. These changes have prompted some to suggest that NCUSIF’s financial design is inadequate — a mistaken judgment I will challenge.

NCUA published NCUSIF’s audited financial statements for 2008 and 2009 only after a prolonged delay. With these audits NCUA changed accounting standards creating confusion, misleading presentations and uncertainty about what assets were audited.

The NCUSIF is unique due to its cooperatively underwritten financial structure. To provide relevant responses to NCUA’s request requires agreement on basic facts. NCUA’s changes in 2000 deviated from the NCUSIF’s prior consistent accounting practices used since the 1984 redesign was approved by Congress.

These changes resulted an ever increasing draw on the NCUSIF to pay a larger proportion of NCUA’s operating expenses and underpaying dividends to the credit union owners.

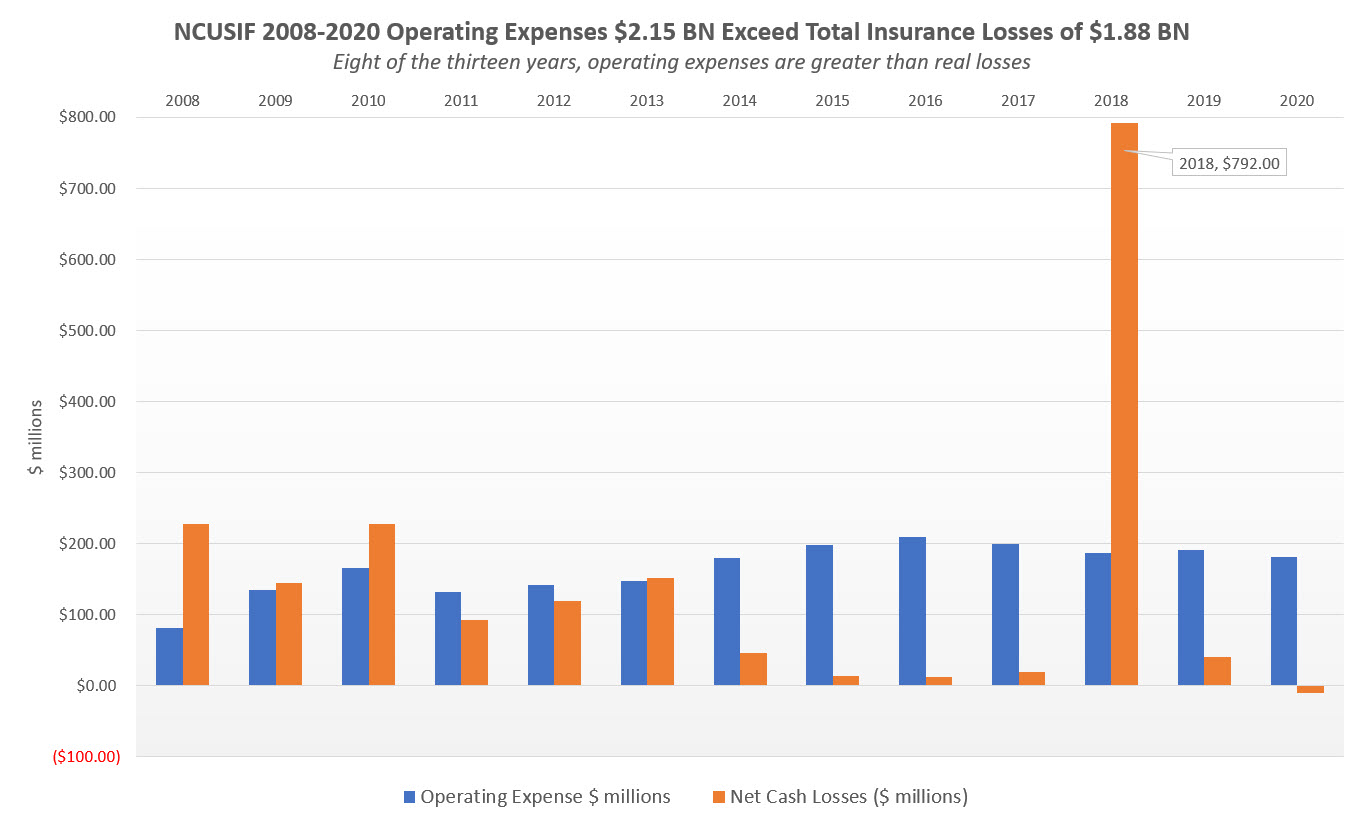

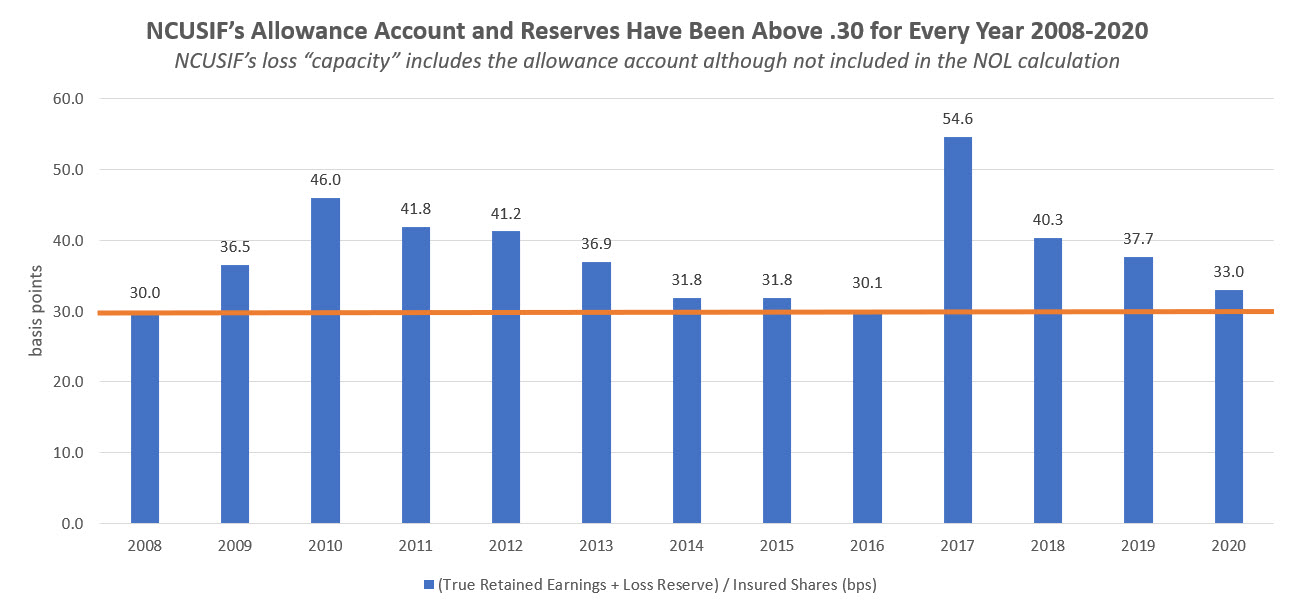

Since 2008 and two financial crises, the data show that the NCUSIF’s operating expenses exceed insurance losses from problem credit unions. Instead of a capital reserve helping credit unions, the NCUSIF has become the main source for financing the agency’s administration, not the required operating fee.

The following is a description of these significant changes in NCUA’s management of the NCUSIF.

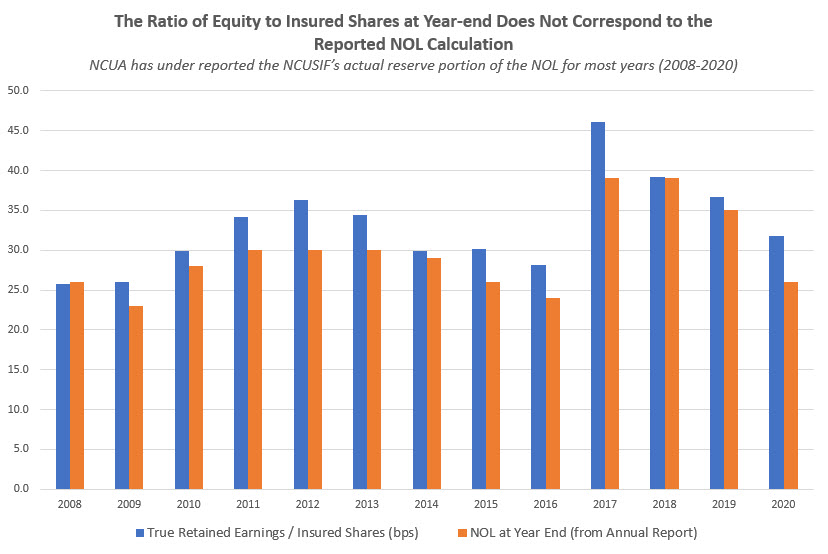

Manipulation of the NOL

From 1984 though 2000, NCUA was consistent in its calculations of the NOL. Credit unions’ 1% deposit funding obligation has always been an explicit legal liability. As stated in the Act: Federally insured credit unions are required to maintain a deposit equal to one percent of their insured shares with the Insurance Fund. 12 U.S.C. 1782(c)(1)(A)(i).

In the NCUSIF’s 2000 Annual Audit, this 1% capitalization and NOL calculation are reported as follows in audit footnote 5.

“The Credit Union Membership Access Act (CUMAA) of 1998 mandated changes to the Fund’s capitalization provisions effective January 1, 2000. . . The NCUA board has determined the normal operating level to be 1.33% as of December 31, 2000 which considers an estimated $31.9 million in deposit adjustments to be billed to insured credit unions in 2001 based upon insured shares as of December 31, 2000. . . The CUMMA mandates that the use of year-end reports of insured shares in the calculation of the specified ratios, and the dividends related to 2000 will be declared and paid in 2001 based on insured shares as of December 31, 2000.”

This 1.33% ratio was calculated by dividing NCUSIF’s audited reserves plus 1% of yearend insured shares by total insured shares. This method was the basis for sending credit unions a sixth consecutive dividend from 1995 through 2000.

But in 2001, the Board changed this calculation both retroactively for 2000 and going forward in 2001 and ever after. This change is described in footnote 5 in the 2001 audit:

“The NCUA Board has determined that the normal operation level is 1.30% as of December 31, 2001 and December 31, 2000. The calculated equity ratio at December 31, 2001 was 1.25%. The equity ratio at December 31, 2000 was 1.33% which considered an estimated $31.9 million in deposit adjustments billed to insured credit unions in 2001 based upon total insured shares as of December 31, 2000. Subsequently such deposit adjustments were excluded and the calculated equity ratio at December 31, 2000 was revised to 1.30%.“

However, NCUA did pay the previously calculated dividend for 2000 based on the initial 1.33% NOL. “Dividends of $99.5 million which were associated with insured shares of December 31, 2000 were declared and paid in 2001.”

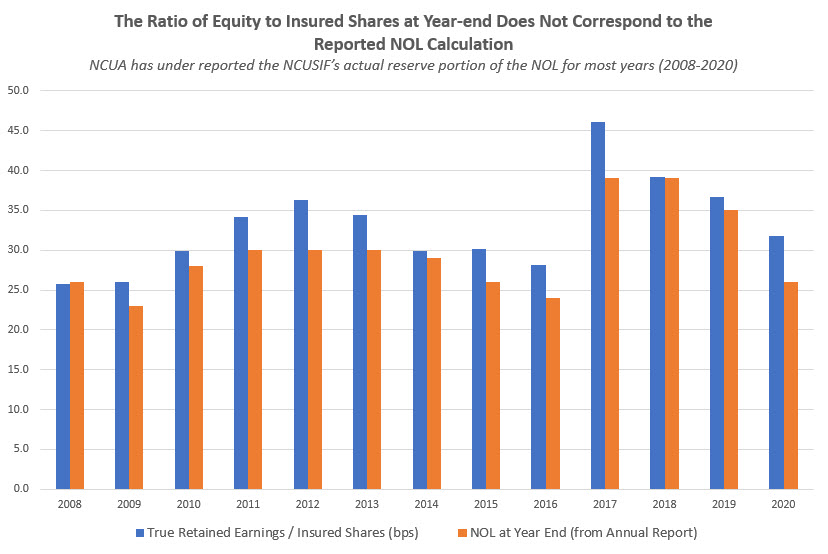

If the same method of calculating equity to insured shares ratio in 2000 were applied in 2001, the resulting NOL would be 1.303%– not 1.25%– thus triggering a small dividend.

By undercounting the full 1% deposit NCUA avoided paying a dividend. It misstated the actual NOL of 1.3% by 5 basis points, a significant reduction.

There was no basis for this change. In every year prior to 2001 NCUA sent invoices after yearend. That is the case today as NCUA bills credit unions their required true-up on insured savings after receiving the yearend call reports. The yearend NOL determination is easy and transparent– both the audited reserves and credit unions’ report of insured shares are available at the same time from the same source.

In making this arbitrary change to the NOL calculation, NCUA has understated the actual NOL to the present day. The underreporting of this ratio meant NCUA did not pay dividends as required (as in 2001) and understated the actual NOL ratio.

Graph Heading; NCUA’s Reported NOL Understates NCUSIF’s Actual Capital Ratio (2008-2020)

Changing the OTR in 2000

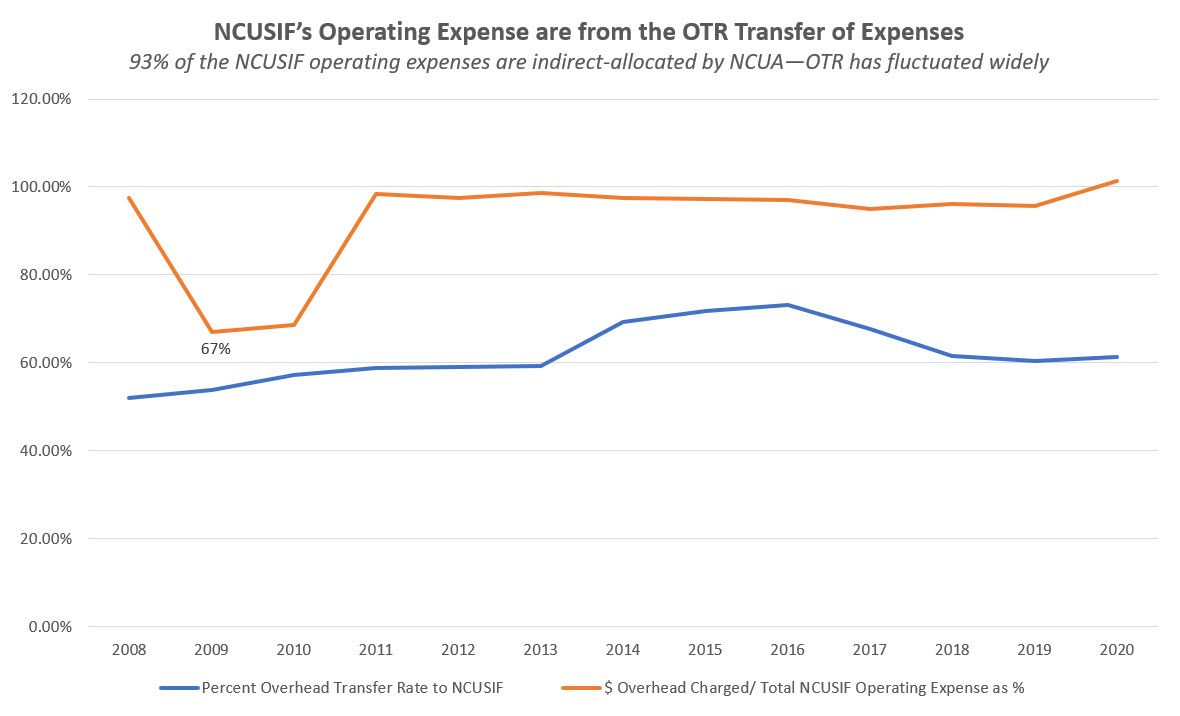

Another NCUA draw upon the fund began at this time. In 2000 NCUA increased the percentage of its operating expenses charged to the fund via the Overhead Transfer Rate (OTR). The change from 50% to 66.7% was a 33% increase in just one year. This increase occurred even though state chartered federally insured credit unions (FISCU’s) were only 44% of the total 10,316 of the NCUSIF’s insured base.

The agency continued to use this annual transfer in uneven and undocumented patterns reaching a peak OTR of 73.1% in 2016. This increase reimbursement for agency expenses and understating the actual NOL resulted in no or only partial dividends due the credit union owners. This dividend drop-off took place even though insured losses from 2001 until 2008 were either 0 or less than 1/2 of a basis point.

For example, in the 2006 audit, the NCUSIF declared an NOL of 1.304 requiring a dividend of $51.5 million. The actual ratio was 8 basis points higher and should have resulted in $103 million more paid out but which was kept in the NCUSIF.

No Timely Numbers and Changing Auditors

In the midst of the 2009 financial crisis, NCUA conserved US Central and WesCorp. Chairman Michael Fryzel asserted in a March 21, 2009 Wall Street Journal interview, “With us in control, we’d get honest numbers.”

That is exactly the opposite of how NCUA reported its own numbers for the NCUSIF. All the corporates routinely filed and published full 5310 monthly financial reports with current portfolio valuations within 30 days of every month end. The corporates were managing over $100 billion in investments. But NCUA did not release its December 2008 NCUSIF audit until a year and a half after yearend.

During this period of uncertainty, NCUA took the following steps:

- It replaced the NCUSIF’s 2008 auditor Deloitte, Touche with KPMG for 2009;

- It changed auditing standards–from private GAAP to government GAAP;

- It released the December 2008 audit on June 10, 2010, 15 months after the statutory April 1 deadline for reporting to Congress.

These actions typify a reporting entity with serious managerial difficulties subsequently noted by both auditors.

By delaying the release of the numbers, credit unions did not know the status of the fund. NCUA statements ranged from Chairman Fryzel’s assurance in the WS J that “regulators aren’t concerned about the health of any other wholesale credit unions besides the two brought into conservatorship” to wild exaggerations of losses that would cause write off of credit unions’ 1% deposit base.

The corporates managing the problem assets reported timely; NCUA did not.

NCUA provided few factual updates to counter the rampant hyperbole. Meanwhile the economy showed positive growth in GDP and market valuation recovery beginning in the fourth quarter of 2009.

Without NCUA’s numbers, credit unions were in the dark about how a mutual solution might be developed to minimize loss using the collaborative financial tools of the CLF and NCUSIF.

Late Reporting and Changing the NCUSIF’s Accounting Standard

Until 2009, “the NCUSIF historically prepared its financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America (“GAAP”), based on standards issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”), the private sector standards setting body.”

The issue following this standard was whether US Central and or Wescorp, conserved in March, must be consolidated with the NCUSIF under the Variable Interest Entity (VIE) rule. As a subsequent event and prior to the completion of the December 2008 audit, the VIE presentation needed to be resolved. As stated in their audit, this situation was one indication that NCUA did not fully grasp the consequences of their actions.

The resolution of this was described in the audit notes for 2008:

It was concluded that for 2008 the NCUSIF would be the primary beneficiary of certain identified VIEs based on variable interests held by the NCUSIF at December 31, 2008, and therefore, the NCUSIF would have been required to consolidate such VIEs in its financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2008. However, based on the actions discussed below, it was concluded that the TCCUSF would be the primary beneficiary of these same VIEs based on variable interests held by the TCCUSF at December 31, 2009.

The shift in primary beneficiary from 2008 to 2009 was the result of the June 18, 2009, actions of the NCUA Board to transfer the legal obligations related to CCUs from the NCUSIF to the TCCUSF. Such actions relieved the NCUSIF for the costs and related obligations of stabilizing the CCU system, as provided by Public Law 111-22, which was enacted May 20, 2009.

This change in reporting entity has been applied retrospectively to 2008. Accordingly, the accompanying financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2008 do not reflect the consolidation of any CCUs.

Avoiding Private Auditing Standard Requirements

To avoid VIE accounting requirements, NCUA in its September 16, 2010 public board meeting adopted federal GAAP. These are excerpts of this discussion:

Mary Ann Woodson, the agency’s CFO at the time: The purpose of this action is to request Board approval for the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund to adopt accounting standards promulgated by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, also known as FASAB. These standards are also commonly referred to as Federal GAAP.

The Share Insurance Fund currently applies Financial Accounting Standards Board, or FASB, standards. These accounting standards are used by commercial businesses in keeping their books and records and in preparing their financial statements.

On June 17, 2010, the NCUA Board adopted FASAB accounting standards for the Temporary Corporate Credit Union Stabilization Fund. Since then, we have gained more experience with FASAB and we have seen firsthand that FASAB standards more appropriately meet the financial reporting requirements of the NCUSIF and its stakeholders. Also, FASAB is the preferred standard for federal entities. . .

Debbie Matz, then NCUA Chair: So, if we had switched to this before last year, we wouldn’t have had the long drawn-out issue with the auditors that required us to meet with FASB in order to get a clean audit opinion at the end of last year, but it would have eliminated the inconsistencies and vagaries that created that situation?

Mary Ann Woodson: Certainly it would have helped. Yes.

Debbie Matz: Well, then I support it. Thank you.

Both auditing firms commented that NCUA did not understand or follow basic auditing procedures whichever standard was in place:

The 2008 and 2009 NCUSIF audits released on June 10 and 11, 2010 included auditor’s comments on accounting deficiencies. The 2008 Deloitte audit reported “material weakness” in NCUA’s failure to “properly identify the appropriate accounting treatment under Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities with respect to its variable interests in certain corporate credit unions.”

KPMG’s 2009 audit reported a “significant deficiency.” The SIF, the report states, “does not have sufficient staff resources with the experience in technical accounting and reporting requirements that the entity requires to consistently perform certain internal control activities, particularly those related to the preparation and review of the financial statements. . . The SIF does not have procedures in place that require review and approval of the journal entries and related supporting documentation.”

Adopting a Misleading Accounting Standard

In this 2010 board meeting NCUA adopted federal GAAP as the “preferred standard for federal entities.” But it did so only for the NCUSIF in order to avoid certain disclosures according to Matz’s question. However the Operating Fund and CLF continued and are still audited using FASB GAAP.

The problems adopting Federal GAAP are much greater than VIE disclosures. First the NCUSIF is not a federal entity, but rather a cooperatively funded capital reserve for the credit union system. There are no federal appropriations or funds involved.

Investments are in Treasury securities, but that does not make the NCUSIF a government entity any more than it would a credit union holding the same investments. The NCUSIF is totally privately funded and only for credit union system use.

The Federal GAAP income statements and balance sheets are confusing and misleading for credit unions. As explained by Woodson, the agency’s then CFO: “Under FASB, or commercial GAAP, the focus is on netting revenue against expenses for either a net income or a net loss. Under FASAB, or Federal GAAP, the focus is on the cost to government. So we start with the costs and reduce that amount by any revenue earned, to get to the total cost of operations, or said another way, the net cost to the government.”

Under FASAB the focus is on separating transactions within the government from those with the public. But all NCUSIF transactions are with credit unions, that is, the public.

The FASAB balance sheet presentation and income are prepared to show these two activities, but are totally irrelevant to how the NCUSIF operates. The numbers presented in this manner are at best confusing and at worst, misleading.

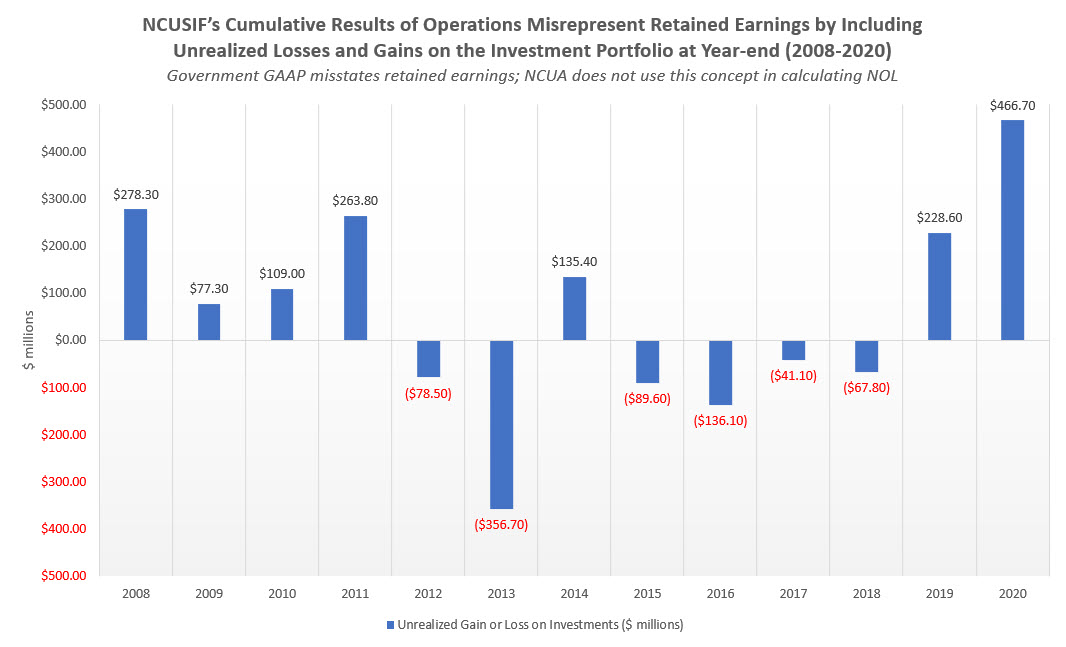

For example, under Federal GAAP the fund’s retained earnings are described as the Cumulative Result of Operations. This description includes unrealized gains and losses on the NCUSIF investment portfolio which can over or understate actual equity significantly.

In the NCUSIF fiscal 2020 results using Federal accounting, it reported a $500 million increase in its net position to a total of $5.1 billion. However, the actual net income from operations was only $32.9 million. This number is nowhere in the Federal GAAP statements-but reported on Slide 3 in the NCUA’s staff December 31 presentation to the board using private GAAP. This substantial difference in the increase in total equity of $400 million versus operating income of $33 million is due primarily to including additional unrealized gains in NCUSIF investments from the prior year.

NCUA staff reports the total of the federal Cumulative Result in its slides. But when calculating the NOL, staff eliminates any unrealized gains or losses highlighting the confusion between the two standards when presenting financial performance.

The difference in NCUSIF’s actual retained earnings and “cumulative results of operations,” varies by hundreds of millions each year (2008-2020) as shown below.

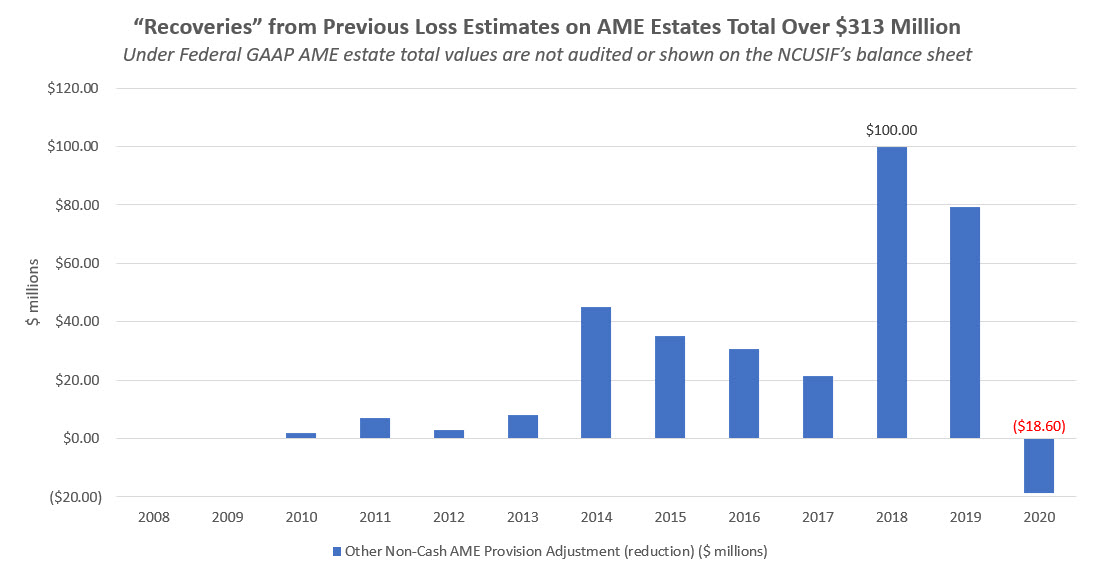

However the most serious defect in federal GAAP is that “fiduciary assets” are non-governmental and therefore not on the NCUSIF’s balance sheet. These are all of the AME’s including the corporate estates which total billions. They are in effect off the books.

As stated at the top of the AME financials issued by NCUA, the amounts are unaudited. Under private GAAP these amounts would be audited and included on the NCUSIF’s balance sheet. Currently the amounts for corporate and natural person AME’s are presented in Federal GAAP as “net” receivable assets subject to various accounting and income recognition rules.

Using the Proper Accounting Standard in a Consistent, Transparent Manner is Critical

To evaluate the NCUSIF’s financial design and capital adequacy, an essential first step is adopting private FASB accounting. This is how NCUA staff routinely presents the board with NCUSIF slide updates—except for the balance sheet entry showing “cumulative results of operations.”

Returning to this accounting standard will help all users more easily understand when monitoring the fund. It will:

- Present financial performance in a standard balance sheet and income statement format readily understood and monitored by credit unions;

- Restore the NOL calculation as was done from 1984 through 2000. The misleading recognition of the 1% deposit, citing a billing delay, is inconsistent with credit unions’ standing legal liability and misstates the fund’s actual NOL status at yearend.

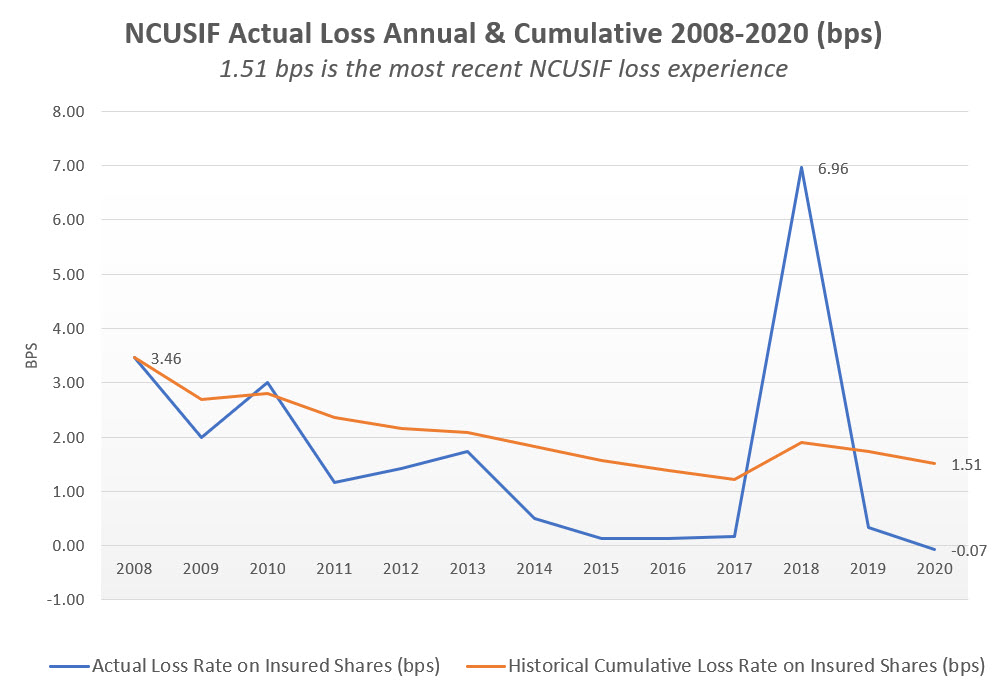

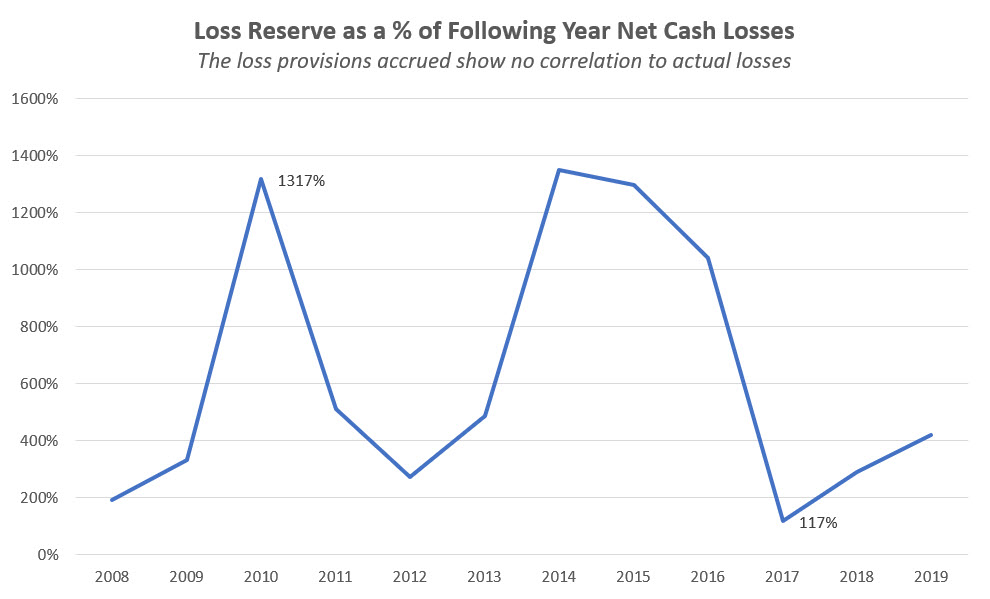

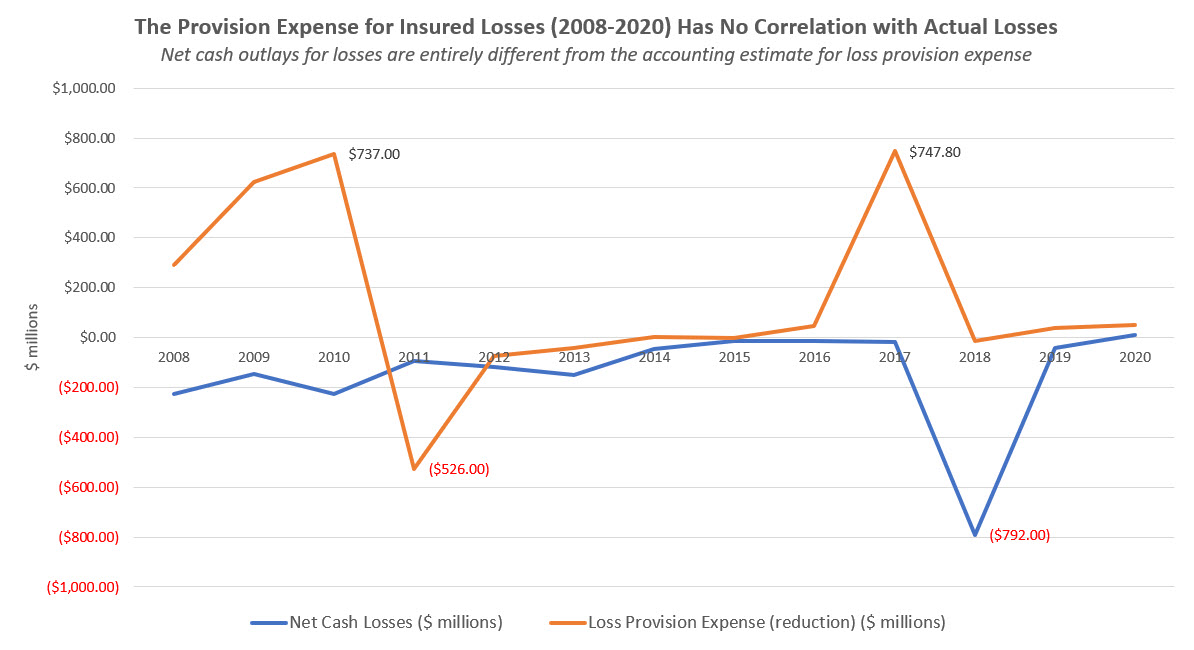

- Bring more rigorous consistency to estimates of loss provision expense. Since 2009 there has been no relation between the provision expense and actual cash losses.

- Shed greater insight into NCUA’s decisions including the management of its investment portfolio, the AME’s and the probability of premiums or dividends at yearend.

These accounting distortions have contributed to questions about the fund’s sufficiency and flexibility in a low rate environment. This is an important issue in the current environment. But it can only be analyzed if there is a rigorous, objective and consistent presentation of performance.

The fund’s revenue is primarily dependent on the yield on the investment portfolio. But whether that will be a factor causing a premium depends on two other critical events:

- What is the expected level of actual losses to the fund (versus the seemingly arbitrary loss provision expense)?

- Will the NCUA’s ever growing expenditures transferred to the NCUSIF be brought into better alignment with proportionate share of state insured credit union risk?

Tomorrow I will present the NCUSIF’s cumulative performance from 2008-2020 to address the question, does the unique NCUSIF design still work after the two worst financial crises since the Great Depression?