Jimmy Carter’s life is a witness to making a transformative difference in the world by personal example and faith, versus the power of a position. This Thursday, January 9th, his legacy will be honored in a ceremony at Washington National Cathedral.

He has stated that the two great formative experiences of his life were the Great Depression and WW II. Today those events and their lessons seem from another era.

When he first announced his Presidential ambitions in December 1974, a Gallup poll asked voters to rank 31 potential democratic candidates. His name was not on the list. Yet just two years later he won the first primaries in Iowa and New Hampshire defeating nationally known opponents including Senators Scoop Jackson, Ted Kennedy and Robert Byrd.

At the July 1976 convention, he became the democratic presidential nominee.

He was a Southern Baptist who taught a Sunday School class whatever his position—as Governor, as President or as a private citizen. He lived his faith not by telling others what to believe, but by example.

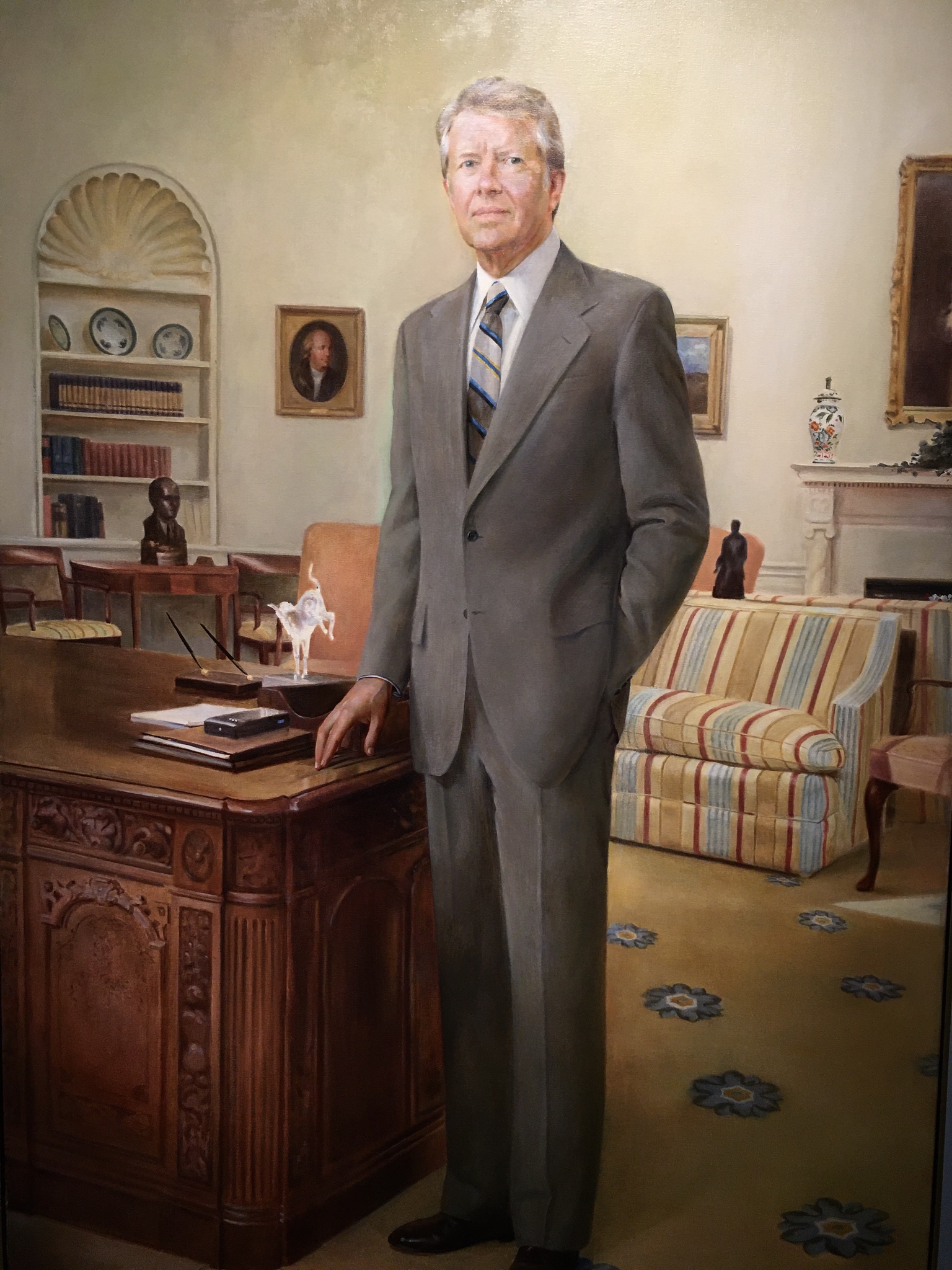

In this official portrait by Robert Templeton (1929-1991), Carter is standing in the oval office as it was during his tenure. On the desk is a crystal donkey statute, a gift from the Democratic National Committee. This oil on canvas 1980 painting is in the National Portrait Gallery.

His Presidency and Credit Unions

Credit unions, as in other segments of the economy, were entering a period of regulatory and market transformation. Carter’s one direct initiative for coops was to ask congress to charter the National Cooperative Bank in 1978. The bank’s purpose was to advocate for America’s cooperatives and their members, with emphasis on serving the needs of communities that are economically challenged.

However, the unique role of credit unions in America’s financial system was not a singular focus.

Rather, changes in the industry during his four years were largely driven by credit union’s specific legislative efforts and external economic events. The destabilization of oil prices led to rising energy costs, increasing inflation and ultimately, the highest interest rates seen in the 20th century. These economic factors helped spark the need and response for the policy of deregulation in multiple sectors of the economy.

NCUA’s Institutional Redesign

Within the federal bureaucracy, Congress re-established the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) as an independent agency in the executive branch on November 10, 1978 (12 U.S.C. 226).

The NCUA’s Central Liquidity Facility Act (CLF) (12 U.S.C. § 1795) was also created by Congress in 1978. The purpose was to provide credit unions their own source of liquidity similar to the Federal Reserve System’s discount window for banks and the FHLB system for S&L’s.

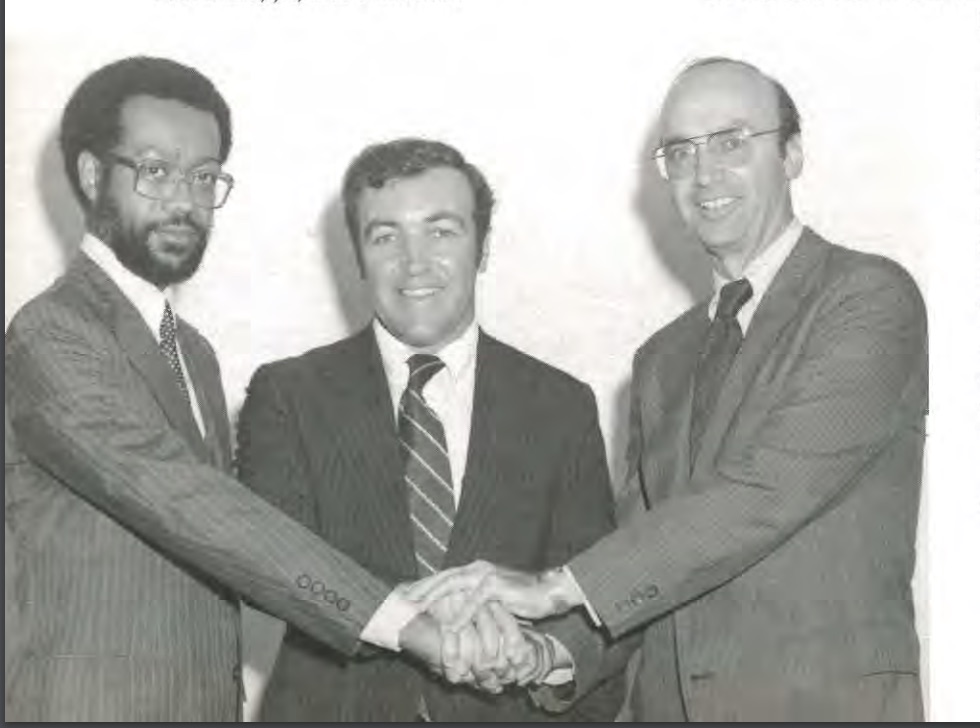

NCUA’s restructure gave President Carter the opportunity to appoint the three initial board members:

Lawrence Connell, Jr. – The Chairman, had previously been Connecticut Bank Commissioner. He served in the office of the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) from 1958 to 1968.

Dr. Harold A. Black – A PhD economist, Dr. Black as a board member brought academic and financial expertise. He helped to integrate his 1962 freshman class at the University of Georgia.

P.A. Mack, Jr. – Served as Vice Chairman. Since 1971 he had been administrative assistant to Indiana Senator Birch Bayh. Mack was reappointed to a second term by President Reagan in 1984.

This was the administration’s most direct impact on credit unions. It followed the practice that personnel appointments in government are in fact policy. In his Presidential appointments, Carter tried to make the government more representative of the American people. His domestic policy advisor Stuart Eizenstat stated that Carter appointed more women, Black Americans, and Jewish Americans to official positions and judgeships “than all 38 of his predecessors combined.”

In terms of enhanced member services, in 1977 credit unions lobbied Congress to authorize mortgage lending and share certificates for FCU’s, products that had been available in multiple state charters for years.

Economic Forces Precipitate Deregulation

Inflation hit 14% in 1980 and led to ever rising interest rates creating financial crises across major industries dependent on energy and sectors reliant on stable interest rates. These sectors were often subject to government regulations that set consumer prices, or rates paid to savers and charged to borrowers. These regulated industries were often limited in the scope of their services and in turn protected from direct market competitors.

Deregulation of these government-controlled sectors was introduced by the CAB in the airline industry, in long haul trucking, railroads and finally, the national monopoly known as Ma Bell, the AT&T phone company. The Carter administration also deregulated beer production, sparking today’s craft brewing industry.

Financial Services Deregulated

Financial firms reliant on charters and deposit insurance were especially impacted by the sudden and increasingly volatile rise in interest rates. In response, Congress passed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA ) signed by President Carter on March 31, 1980. DIDMCA had profound effects on financial institutions, including:

- Increased Deposit Insurance: Raised the deposit insurance limit from $40,000 to $100,000 on individual savings accounts.

- Authorized Interest-Bearing Transaction Accounts permitting credit unions and savings institutions to offer checking accounts, rather than relying on banks as payable through agents for their “share drafts or NOW accounts.”

- Phased Out Interest Rate Ceilings for the banking industry by June of 1987. However, in March 1982 the NCUA board under Chairman Callahan eliminated all constraints on the terms and interest for savings in one regulatory action versus the six-year phased process implemented for S&L’s and banks.

In his signing statement, President Carter made only a brief reference to the bill’s impact on consumers: This is not only a significant step in reducing inflation, but it’s a major victory for savers, and particularly for small savers.

Following the 1980 DIDMCA legislation, NCUA authorized Share Draft Accounts, a service that banks had contested when introduced by state-chartered credit unions earlier in the decade.

A final administrative action triggered by inflation was Executive Order 12201—Credit Control of March 14, 1980. In this order, President Carter granted the Federal Reserve authority to control the growth of credit, including all loans extended by credit unions and other financial intermediaries. The intent was to lower inflation by limiting loan demand growth at the institutional level.

An Agency in Need of Administration

Other than the three NCUA board appointments, President Carter’s administration had little direct comment about the cooperative financial sector.

When Ed Callahan became NCUA Chair in October 1981, the agency was still in a period of reorganization. Agency staff was top heavy in DC with 16 separate offices including a consumer examination program run independently of the six regional offices. There were departments doing tasks and reports the same way as ten years earlier, despite the new challenges of deregulation. Examinations were on a two-year cycle, at best. Semiannual call reports were not collected from all credit unions. The NCUSIF was cash poor and used 208 assistance to help credit unions regain solvency. The CLF had only several of the over 40 corporates as agent members, and only a handful of the almost 16,000 natural person credit unions had joined. There was uncertainty about how the CLF itself would be funded. In brief, the NCUA in 1981 had too much regulation and not enough administration.

Carter’s Legacy

Most of the changes in NCUA structure, the CLF, and even the enhanced mortgage and certificate services were sought by credit unions and underway before Carter took office in January 1977. Credit unions had seen deregulation work at the state level but implementing that policy on a national basis was at best uncertain.

The combination of economic headwinds and changing market competition led CUNA President Jim Williams to say their primary goal was “survival” at the February 1982 GAC conference. In response Chairman Callahan in his first GAC address said the solution was deregulation for credit unions coupled with a simultaneous upgrading of the agency’s supervisory capabilities.

A Leader’s Impact

However Carter’s influence goes far beyond his time as President. While his administrative and policy challenges were not viewed as successful when he left office, his insights and leadership perspective are now being reassessed. For example, his reasons for establishing independent departments for energy and education are now seen as critical to America’s future.

But the most memorable contribution may be his calls to common sense individual accountability. In his 1979 “Crisis of Confidence Speech” he challenged Americans to acknowledge their responsibility for the urgent national economic worries. He said in part:

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

His concern about society’s desire for the bigger, the newest, the “always more” is still a dominant motive today. For a person who grew up on a peanut farm in rural Georgia, lived through the depression, and who left military service to run the farm when his father died, character mattered more than material net worth.

Capitalism promotes and relies on consumer demand. This incessant drive has become endemic in society. When credit union leaders talk about progress in terms of billions, have we lost the cooperative focus on member well-being to the market’s alternative ethos of institutional dominance?

The title of his first book when announcing his intention to run for president was Why Not the Best? It was about renewing the can-do American spirit. The question Carter poses for us is can we invert our thinking about credit unions as successful financial institutions and again see them as a movement by and for the people.

An elegy for Jimmy Carter, Jr.

by Paul Hooker, a retired Presbyterian pastor, presbytery executive, and professor who lives in northeast Georgia

Goodbye, fierce and gentle warrior,

farmer with your hands full

of good soil. You grew things.

You made your choices for weal and woe,

held your power loosely, let it go;

asked nothing of others

you asked not of yourself.

In extraordinary times, you were an ordinary man —

not a hero, not a saint, not a role model.

You looked into our eyes and told the truth

as best you understood it. We did not listen.

We wanted fairy tales of false greatness,

glib promises of never-ending good times,

eternal morning in a land immune to night —

Lies, all, and so you warned us.

But comforting calumny is easier to hear

than stony fact. We turned away

to worship at their shiny altars

these gods of glory, greed, and gore.

You wavered not an inch from your convictions,

smile undimmed by public humiliation;

you went back to planting crops

in fields where no one else thought they could grow:

Peace in bloodied ground,

homes in urban lots,

love stretched like a wedding canopy

over time and patience and simple faith.

Do not despair.

The fields you plowed still wait their harvest.

See, even now they bear your quiet fruit.