I had the opportunity to listen to a very small slice of NCUA’s Board’s public budget process for 2025-26 by watching the video of the November 21 discussion of the CLF’s spending requests for the next two years.

Although extremely small in the agency’s overall spending totals, I fear we see clearly in this simple example, the board’s inability to substantively assess spending requests.

A Brief Background

Several items from the CLF’s board action memorandum for November 21 provide some background for the hearing including these two points:

The purpose of the CLF is to improve the general financial stability by providing member credit unions with a source of loans to meet their liquidity needs and thereby encourage savings, support consumer and mortgage lending, and provide basic financial resources to all segments of the economy. and,

“(CLF) is owned by its member credit unions and managed by the NCUA Board”

CLF’s budget proposals were for $2,307,863 for 2025 and $2,448,263 for 2026. Salaries and benefits are 96% each year’s requests.

Several facts put this credit union owned public-private effort in perspective.

Total membership is 430, an increase of 32 in 2024, and 9.4 % of all credit unions. CLF’s balance sheet is $966 million and includes $44 million of net worth/retained earnings.

The Board’s Policy Failure

Each board member remarked on some aspect or other of the financials. Otsuka had no questions. She made an unexplained reference to “protecting the insurance fund.” Hauptman called the CLF a “buffer for the American taxpayer” and cited a vague reference to $18 billion of loans sometime in the past.

He reverted to his standard routine of demonstrating how to improve the “user experience” when contacting the CLF. He showed how staff had “made it easier to access” the CLF by removing the on-hold music replaced by an automated telephone routing message. He confirmed that a credit union inquiry would ultimately end at the CLF President’s desk, if no one else picked up the call before then.

He also pointed out that 3,300 credit unions (95% of those under $250 million in assets) had lost access when the special CLF-Corporate membership authority expired. Hauptman opined that credit unions should have multiple liquid cash sources which is how he arranged his personal financial management: “a credit card, home equity line and a margin loan established with a broker.”

As Chair Harper led off the discussion, one would have hoped for a focus on CLF policy and whether its purpose above was being carried out. Instead, he supported the budget in full and noted the 31 increase of members. He did ask about the cost of membership. The 4.46% third quarter member dividend was the only recognition that the CLF’s return to the owners was below market rates including the overnight Fed Funds yield. He again complained about Congress not renewing the special CLF authority for corporates to join by funding only a subset of their members.

Business as Usual While Failing the Owners

A critical capability of any NCUA board member is discernment. What is their understanding of the key issues in a staff presentation, especially when focused primarily on budgets? Is It really about numbers? Or should it be about whether the CLF is serving its owners?

All three board members stated that the CLF existed for the benefit of NCUA and the NCUSIF, not for the credit union funding owners. What are credit unions getting for their direct support of the CLF? In the presentation the number one productivity indicator and primary 2025 Planned Activity goal is to Provide CLF Advances as needed.

However, the CLF has not issued a loan to credit unions since 2009. Almost all of those advances, 15 years earlier, were to two corporates via the NCUSIF. They were very short term and not part of any overall recovery plan. I am ignoring a token $1.0 million mini-advance made to a small credit union in December 2023 and paid off early in 2024.

A Time of System Stress

The lack of credit union support and CLF membership is not a statutory shortcoming. It is a management one, an NCUA responsibility as stated in the staff memo above. During the 2022 and 2023 rising Fed rate cycle, liquidity pressures increased throughout the system. This concern peaked when the Silicon Valley and other bank failures occurred. However the CLF was totally missing in action this entire cycle.

Instead, credit unions borrowed in record amounts from the Federal Reserve’s Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) and the FHLB’s. For example, the September 2023 call reports show 307 credit unions with Federal Reserve borrowings of $34.9 billion, an average of $114 million. For these credit unions, the Federal Reserve represents 66% of their total borrowings. For 112 of this group, the Federal Reserve is their only source.

Credit union total assets of $2.25 trillion at 3Q 2023 were just 9.7% of total banking assets. However, their participation in the special emergency Federal Reserve lending program equaled 27% of the BTFP’s loans at yearend or three times cooperative’s share of total industry assets. And this Federal Reserve borrowing was only a quarter of all credit union borrowings at the quarter end of $130.3 billion.

During this entire liquidity crisis, the CLF was nowhere to be found, or even heard. No programs, no outreach, no public discussion. And it was not due to a poorly designed website or failure to target market. Rather the CLF’s credit union owners were completely left out and shut out of any role except sending in capital—for a below market return. The agency made no effort to assist credit unions because the board and staff view the CLF as a liquidity partner for the NCUSIF, not the industry.

Why the CLF Has No Interest is a post from May 2024 which shows that the credit union owners have been subsidizing the CLF due to its below market dividends. The CLF’s return is much less that paid by the FHLBs and corporates on their capital accounts. Even though the CLF has investment authority similar to FCU’s, its own portfolio was underwater at 2023 yearend and its yield trailed the overnight FF rate the entire year. But the board ignored those facts.

Credit unions do not view the CLF as a reliable partner in times of balance sheet stress. They have plenty of tested alternatives. Ones that don’t impose supervisory judgments on top of collateral security. The Board’s view of the CLF to serve the NCUSIF has made it a “vestigial organ” within the NCUA body serving no credit union owner-members.

What the Board Could Have Asked Staff

Following are some questions that board members might have asked if they had really focused on the CLF’s policy failures in this most recent period of liquidity need.

- How many of CLF’s current members have outstanding loans elsewhere? How much and for how long?

- What unused lines do CLF members report on the latest call reports?

- Has the CLF developed any proactive lending programs in the two years since the Fed began raising interest rates in 2022? If yes, how were these communicated to owners?

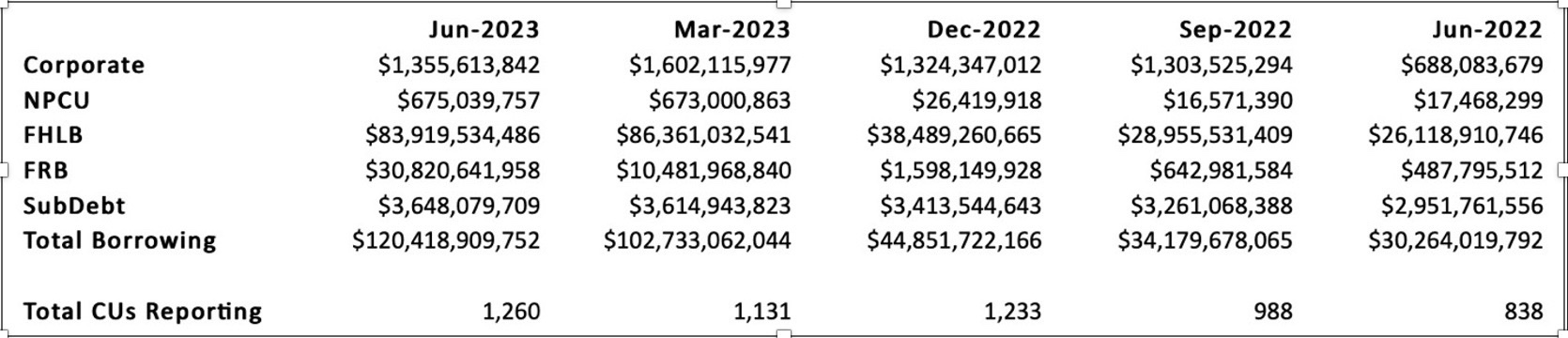

- Given the dramatic increases in credit union borrowing in both total dollars and numbers as shown below, what did the CLF do during the crisis? The chart below would be updated as context for the question.

Total Credit Union System Borrowings (June ’22 to June ’23)

- Why should the CLF continue as a separate department with a staff of six and overhead charged by the NCUA board, when it could easily be a collateral responsibility with other senior examination and supervision staff?

The failure of NCUA board members to ask the most basic questions about CLF’s non-activity while routinely continuing to increase its spending is disappointing. It undermines the NCUA’s capacity to serve the owners of the fund.

The board has failed in its policy oversight role. With zero lending productivity, why is there any reason for a staff of six to keep lights on? The entire system shows increased liquidity demand and draws but relied entirely on every other contingency funding source while its own funded resource was moot.

If credit unions are to get their money’s worth from the CLF, the agency must show leadership by working with the owners. Contrary to one board member’s assertion, CLF effectiveness does not depend on its members; rather it depends on the management by NCUA. Otherwise, just merge the shop back into the bureaucracy from which it came. Save the credit unions money.

Editor’s footnote: If you want to see how another cooperative designed liquidity lender communicates with its owners, read this latest update from the FHLB’s newsletter.