As the 80th Anniversary of the June 6, 1944 Allied landings at Normandy draws to a close, we listen with great interest to the living participants’ stories of that consequential event. They did their part. Now it is up to us that their examples of duty, service and honor be carried forward for freedom’s fight

One might also ask about the state of the credit union experiment at this time. Are there any lessons relevant for today from four score years ago? What examples might inspire current cooperative leaders?

The first surprise is that there is a very comprehensive analysis on the cooperative system including details that are directly relevant for today’s priorities. The source for this information is Bulletin #850, from the Department of Labor titled: Activities of Credit Unions in 1944.

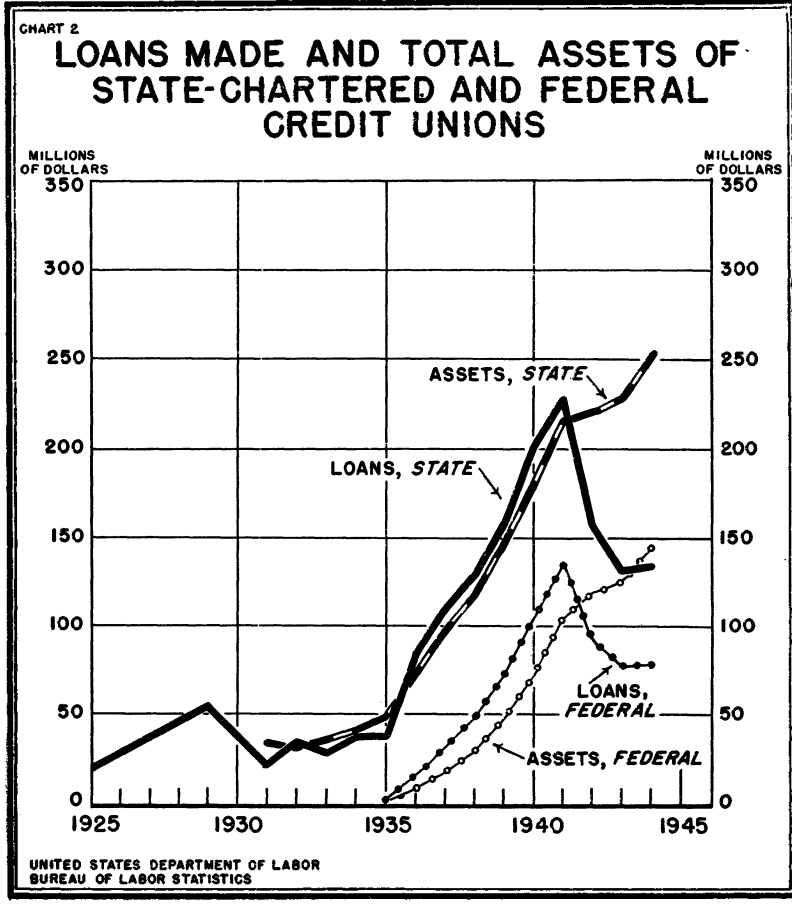

This 16 page report contains historical tables, state and federal totals for numbers of credit unions, total assets and members, number of loans made and dollar amounts outstanding in each state and for national totals. One table records the number of state and federal charters that are active from 1925 through 1944. The cost of the report was just five cents.

Observations on 1944 Credit Union Trends

The impact of the war on credit union lending is central in this analysis:

The entry of the United States into the war was followed by a sharp decline in the credit union movement. Many associations were liquidated, membership fell off, and credit union loans showed a precipitous drop.

This was caused by a number of factors. Among them were the issuance by the Federal Reserve Board of Regulation W (limiting to 18 months—later to 12 months—the period of repayment of installment purchases or loans made for that purpose), the disappearance from the market of higher-priced consumer goods (automobiles, refrigerators, etc.) for which many credit union loans had previously been made, the restrictions on the use of building materials, the emphasis on repayment of debts and the inadvisability of incurring new obligations of that nature, and the increased wartime earnings of wage earners which resulted in a lessened need for credit.

However, some trends were looking better:

Reversing a trend that has been sharply downward since the beginning of the war, both the membership and business of credit unions showed an increase in 1944, although the number of associations was smaller than in 1943.

At the end of 1944 the number of associations on the register totaled 9,099, as compared with 10,373 in 1943. The 8,702 associations active and reporting for 1944 had 3,027,694 members and made loans aggregating $212,305,479. These represented increases, as compared with 1943, of 0.1 percent in members and 1.7 percent in loans.

Total assets which have continued to increase all through the war years, even while number of associations, membership, and business were declining, mounted to $397,929,814, or 12.0 percent above 1943.

The Bulletin also provides a brief history of credit union chartering. Here is one excerpt:

. . .in 1934, therefore, a credit union act was passed by the Congress of the United States and the Credit Union Division was created in the Farm Credit Administration to oversee the carrying out of the law and render various services to the associations formed under it.

From that time onward, until checked by wartime conditions, the credit union movement expanded at an accelerated pace. Not only did the associations with Federal charters spring up and grow, but the older State-chartered movement also seemed to be stimulated to growth considerably faster than its previous pace. The rate of growth of the Federal credit unions, however, was consistently higher than that of the State-chartered associations, and by the end of 1944 the Federal credit unions accounted for 43.1 percent of the members, 36.9 percent of the loans made, and 36.3 percent of the total assets of the credit union movement.

The FDIC Supervises

In 1942 the federal Credit Union Division which was first placed under the Farm Credit Administration was transferred to the FDIC. The FDIC administered the Federal Act but did not insure credit unions, only banks.

What makes the financial details in this report so remarkable is that the totals for the 9,099 credit unions were all maintained by hand. Credit unions used only hand posted card ledgers and total tapes run on mechanical adding machines. There were no databases for quick comparisons, summaries and trends. Given these conditions, the report’s historical tables and graphs are even more remarkable for their thoroughness and timeliness. (the Bulletin is dated October 16, 1945)

The Status of Negro Credit Unions

One of the most enlightening analysis is under a section called Experience of Federal Credit Unions. Here are the details:

The Federal Credit Union Division of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has made available to the Bureau of Labor Statistics certain information on Negro credit unions and on all liquidations of associations organized under the Federal Credit Union Act. Unfortunately, similar data are not available for the State associations.

Negro credit unions

By the end of 1944 a total of 91 credit unions had been organized, under the Federal Act, among Negroes. Of these, 74, or 81 percent, were in active operation at the end of the year, and the remainder were inoperative or had had their charters canceled. For the entire group of Federal credit unions 74 percent were active.

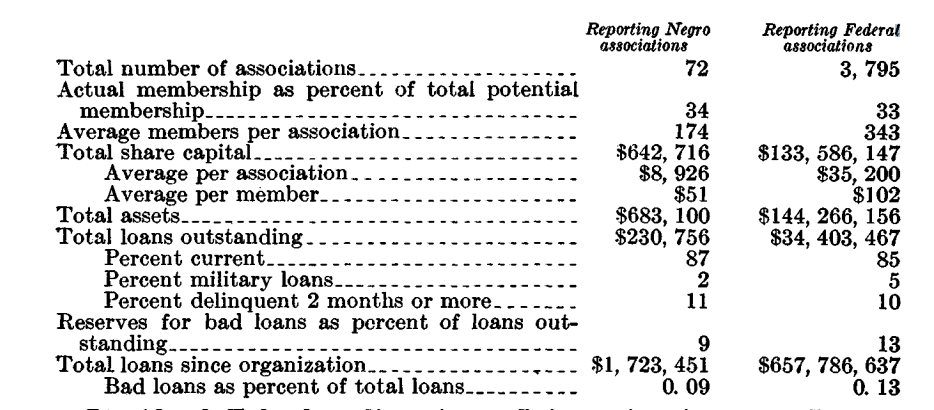

The following tabulation compares the 72 Negro associations for which data were available with the whole group of 3,795 reporting Federal credit unions. As it indicates, the Negro associations, although smaller than the average for all Federal credit unions and less well financed, were holding their own very well and even excelled the showing of the whole group as regards bad loans that had to be written.

Liquidation Information

Information for 1,109 Federal credit unions that were discontinued during the period from June 26, 1934, through 1944 indicates that the liquidated associations were in the main small. Over a third had share capital amounting to less than $500, and 68 percent less than $2,000. Only 18 (1.6 percent) had capital amounting to $20,000 or more.

Of the 1,109 credit unions, 785 (71 percent) returned to the members all of the share capital they had invested and some paid back even more; altogether the members of this group of associations received back $164,955 (or an average of about $2.60 per member) more than they had put into the organization.

The members of the 234 associations that paid less than 100 cents per dollar of share capital sustained an aggregate loss of $20,889 (about $2 per member). Some 65 percent of this loss was accounted for by the associations with capital of $2,000 or less, and 97 percent by those with capital of $5,000 or less.

Sixty-three percent of all cancellations, mergers, and revocations of charter made in the 9 ½ year period took place during the war years of 1942-44.

What This Report Reminds Today

This remarkably candid and thorough report concludes with two pages of updates on Developments in the Credit Union Movement in 1944. This section describes changes in league and CUNA organization and in state chartering regulations.

In just a few pages one finds an important factual and analytical record of the emerging credit union system by 1944. In wartime we rightly honor the contributions and sacrifices of all who serve. How in moments of extreme challenge, ordinary people do extraordinary deeds.

But these same contributions occur on the home fronts, unheralded and frequently taken for granted by their successors. This unique Bulletin is a valuable document about the early contributions of the founders of the credit union system. It is their efforts and commitment, the seeds they planted, that created the foundation on which today’s credit unions built their success.

Ordinary people doing extraordinary things for their communities in the past, now and into the future.