The traditional view of market competition is that it is a zero-sum game. There are winners and losers. Acquirers and the acquired. A credit union gains member deposits, or they go somewhere else.

But endgames do not always happen with clear winners and losers going out of business. Sometimes the losers just limp off the field in irrelevance.

Substitutes slowly absorb earlier organizational efforts with new ones. In credit unions this evolution is already occurring. Two updates from these alternatives were recently announced.

The Federal Home Loan Bank System

This week, the members of the Board of Directors and Executive teams from the Federal Home Loan Banks and the Office of Finance are in Washington DC for their annual conference.

For some time, they have been the primary source of liquidity for the credit union system. Their self-description:

The FHLBanks are 11 regionally based, wholesale suppliers of lendable funds to financial institutions of all sizes and many types, including community banks, credit unions, commercial and savings banks, insurance companies, and community development financial institutions. The FHLBanks are cooperatively owned by member financial institutions in all 50 states and U.S. territories.

The Banks’ regulator the FHFA issued a report last year on their mission and is following up with a request for comments. The primary issue is how well the Banks are fulfilling their mission of increasing affordable housing options in America.

At the conference, the Council announced the Banks anticipate “a record-breaking $1 billion in support for affordable housing and community development initiatives in 2024. This significant commitment reflects our unwavering dedication to our mission and promoting access to safe, affordable housing.”

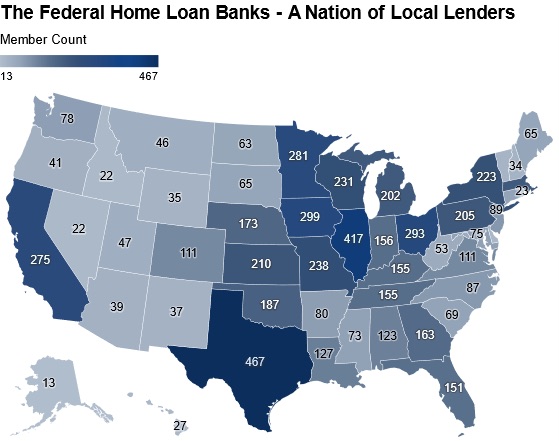

The chart below shows the membership of the banks by state at December 31, 2023. The system serves roughly 6,500 members nationwide with a regional, custom approach from FHLBanks in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Dallas, Des Moines, Indianapolis, New York, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and Topeka.

Since the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the FHLB cooperatives have effectively replaced the lending functions the CLF and corporates were designed to provide the credit union system. Corporates still serve critical payment and short-term liquidity roles. However, the FHLBs have taken over almost all term lending. They do this using a cooperative design.

New Public Banking Legislation

The digital web site Next City has reported on multiple efforts to create publicly owned banks following the model of the North Dakota State Bank. Here is their latest update:

At Next City, we’ve covered efforts to create city-owned banks in Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and the East Bay. We’ve also covered efforts to create state-owned banks in California, Massachusetts and New Mexico. Sometimes, as in the case of New York or California, state legislation has been proposed (and passed in California) to authorize local governments to create their own banks — but none of those efforts have yet reached the point of obtaining a bank charter, accepting deposits and making loans as envisioned.

This month in New York, there’s a new iteration: state legislation that, if passed, would create the Bank of Rochester, a bank that would be controlled by the local governments of Rochester and the encompassing Monroe County.

Technically, the bank would still need to apply successfully for a bank charter from the state’s Department of Financial Services, just like a private-sector bank, before it could accept deposits. Per the legislation, the bank would serve “the public purposes of achieving cost savings, strengthening local economies, supporting community economic development, and addressing infrastructure and housing needs for localities.”

It would not be a bank that accepts deposits directly from members of the public. As laid out in the bill, the Bank of Rochester would be modeled largely after the century-old state-owned Bank of North Dakota. Nearly 90% of the Bank of North Dakota’s deposits come from the state government, which is required by law to use the Bank of North Dakota as its primary bank.

Similarly, the Bank of Rochester would only be authorized to take deposits from government bodies, including local or state government as well as federal offices. It would be restricted from retail banking and raising deposits from individuals and businesses.

Change is the Lifeblood of a Market Economy

These evolutions of financial service providers may seem to nibble only at the margins of the credit union system. However, the relatively recent CDFI option (September 1994) is both a wholesale and consumer response to unmet local borrowing needs for communities throughout the country. Its creation was inspired by Cliff Rosenthal, a credit union and cooperative advocate. Today some CDFI’s are established financial charters; others are stand-alone lending organizations.

The strategic implications for credit unions remains constant: to differentiate their business and service models by focusing on the members they seek to serve. When credit unions look and sound like all other options in a market, members and customers will just look for the best deal, not an owner relationship.

Credit unions have learned the art of tapping member and organizational funds to create large balance sheets. That same skill and funding attracts fintech startups and encourages multiple efforts at public banking.

Raising funds is just the beginning-how those resources are used thereafter is what matters. Is it to make a profit or to serve a community? When community needs are not being met, newcomers will find a way to create options for those underserved. That is what the FHLB and the public banking models are trying to do-serve where others have failed to do so.

Chip,

I’ve been wrestling with this theme – thank you for inspiring this topic!

As I think about the way US CUs are structured, I keep bumping into the question of, is the model we follow the best way to run a cooperative provider of financial services? Or are we taking too much of our model from banks, either because the market seems to push us that way, or because regulators (and I’ll throw the CFPB in there, too) are forcing these behaviors?

If we compare the CU model with, say, an agricultural cooperative (I was in Nebraska last week and had a fun conversation with my Uber driver), how much does our cooperative “wiring” benefit the typical member?

To your point, how much of what we do is truly relevant in the eyes of our members? And how does that break out across member demographics – the low-income, the under-served, or those who have surplus capital to invest in their community?

FHLBanks are providing a needed service but to say they are cooperatives is a joke. By definition, cooperatives have a one member one vote philosophy. Some FHLB’s have almost as many CU’s as members as banks but go look at the Boards of these organizations. There might be 1 or 2 CU CEOs on the board of all them combined due to the voting structure based on stock ownership. There is nothing cooperative about them. Also look at the compensation of directors at FHLBs. Most are making anywhere between 100-200k annually sitting on those boards.

Also, holding a quasi government guarantee allows them to compete somewhat unfairly with others including Corporate CU’s who truly operate as cooperatives.